Inflation in France : CPI or HICP ?

Each month1, the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (Insee) publishes two official indicators to measure inflation in France: the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is the reference index preferred by Insee to analyze national inflation2, and the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), used mainly for international comparison purposes and to assess the price stability criterion under the European Union treaty (Maastricht), and republished by Eurostat. This note demonstrates that, for economic and methodological reasons set at the international level, the HICP provides a more relevant tool than the French CPI for estimating the evolution of living standards, the purchasing power of wages, and other types of income. More generally, it would be logical that the “constant euro” series published by Insee, the Ministerial Statistical Services, and other official institutions be based on the HICP rather than the CPI (or even the CPI excluding tobacco, in the case of Dares). Indeed, the use of the CPI (a fortiori the CPI excluding tobacco) tends to systematically overestimate purchasing power gains in France.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) remains, legally, the reference for most3 short-term indexations. However, one may ask whether it is still relevant to maintain in France a CPI distinct from the European HICP, despite the significant methodological problems presented by the French CPI. Without legislative intervention, a methodological change decided by Insee could bring the calculation method of the CPI closer to that of the HICP. Since the HICP is more dynamic, such a reform would mechanically result in a faster increase in the minimum wage (Smic), benefits indexed to inflation, or even alimony payments. That said, any methodological change to the CPI, whichever direction it takes, already has similar repercussions without requiring legislative intervention.

What are the differences between the CPI and the HICP?

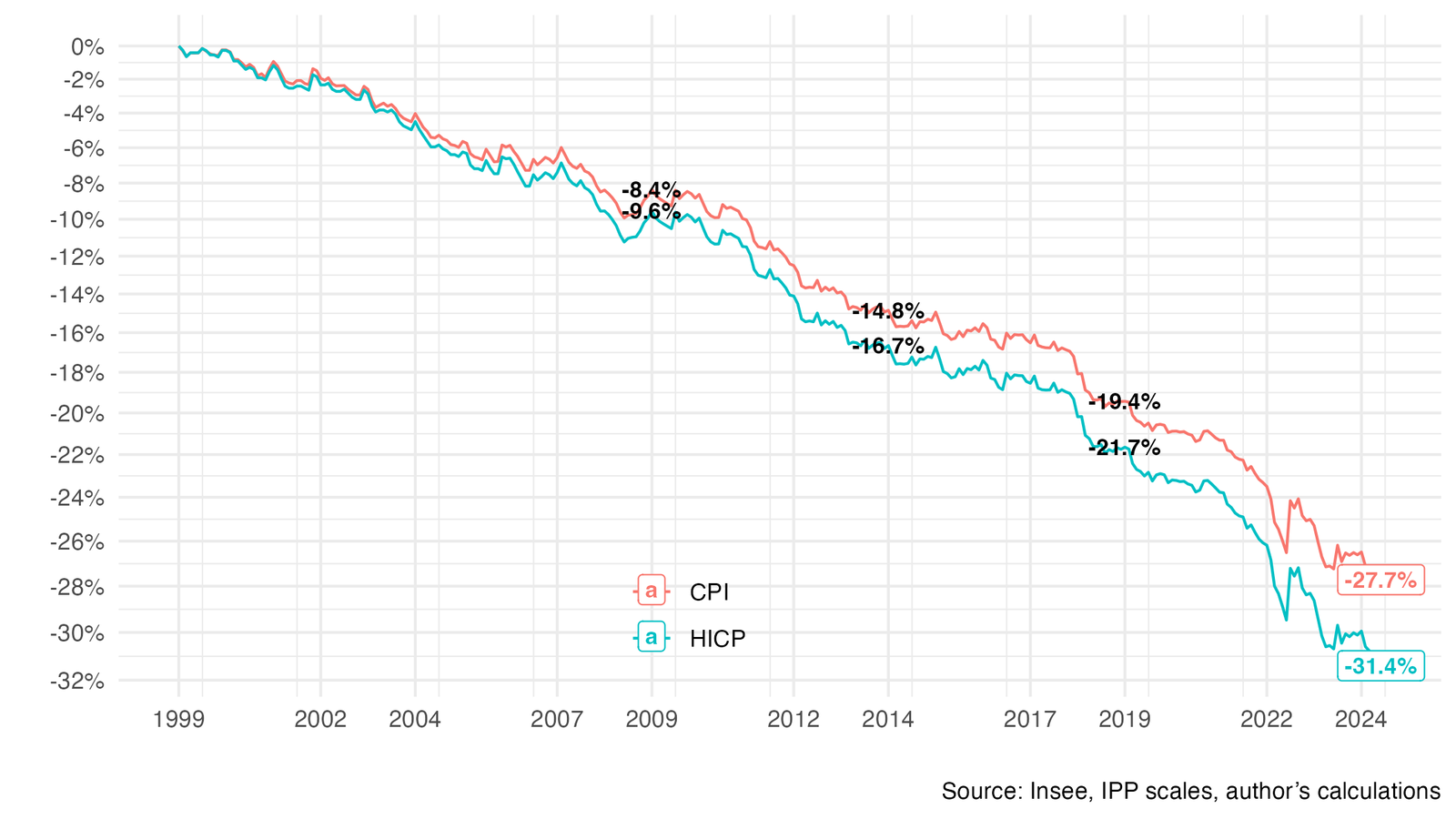

Insee systematically publishes two official indicators to measure inflation: the French CPI and the HICP, harmonised at the European level. Until 2021, a period marked by low inflation, the difference between these two indices was relatively small, that is, between 0.1 and 0.2 percentage points per year. However, with the return of inflation, this gap has widened considerably: in 2022, average annual inflation was 5.2% for the CPI and 5.9% for the HICP, a difference of 0.7 percentage points; in 2023, these figures were 4.9% and 5.7% respectively, a difference of 0.8 percentage points. Over three years, from June 2021 to 2024, the increase was +13.0% for the CPI and +15.1% for the HICP, a difference of 2.1 percentage points. In total, over 25 years, from June 1999 to June 2024, the CPI recorded cumulative inflation of 52.8%, while the HICP showed an increase of 61.0%, a difference of 8.2 percentage points (see Table 1).

| CPI or HICP? | 2022 | 2023 | June 2021 – June 2024 | June 1999 – June 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPI Inflation | +5.2% | +4.9% | +13.0% | +52.8% |

| HICP Inflation | +5.9% | +5.7% | +15.1% | +61.0% |

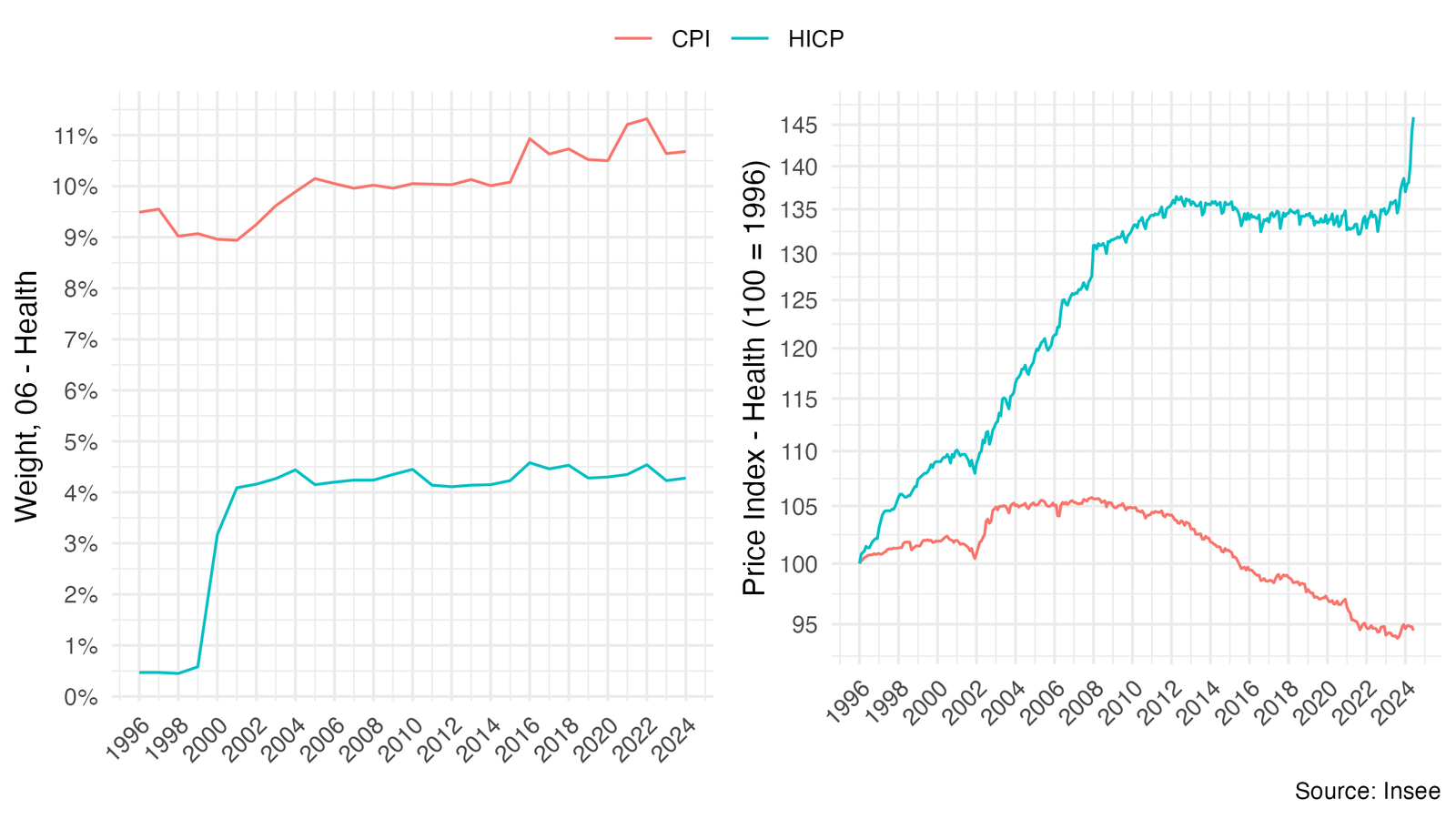

How can such quantitative differences be explained? The main divergence between the methodology of the CPI and that of the HICP lies in the way healthcare expenditures are taken into account. The CPI includes gross prices, i.e. those including expenditures covered by social security, while the HICP considers net prices after reimbursements. This has two consequences: first, the weight of healthcare in the CPI is greater than in the HICP, which mechanically reduces the weight of other items in the CPI. These other items are generally much more dynamic than healthcare, particularly during inflationary periods. Second, the healthcare index in the HICP evolves more dynamically than in the CPI (see Figure 1), since the HICP takes into account the rise in out-of-pocket expenses linked to the increasing delisting of drugs and health services.

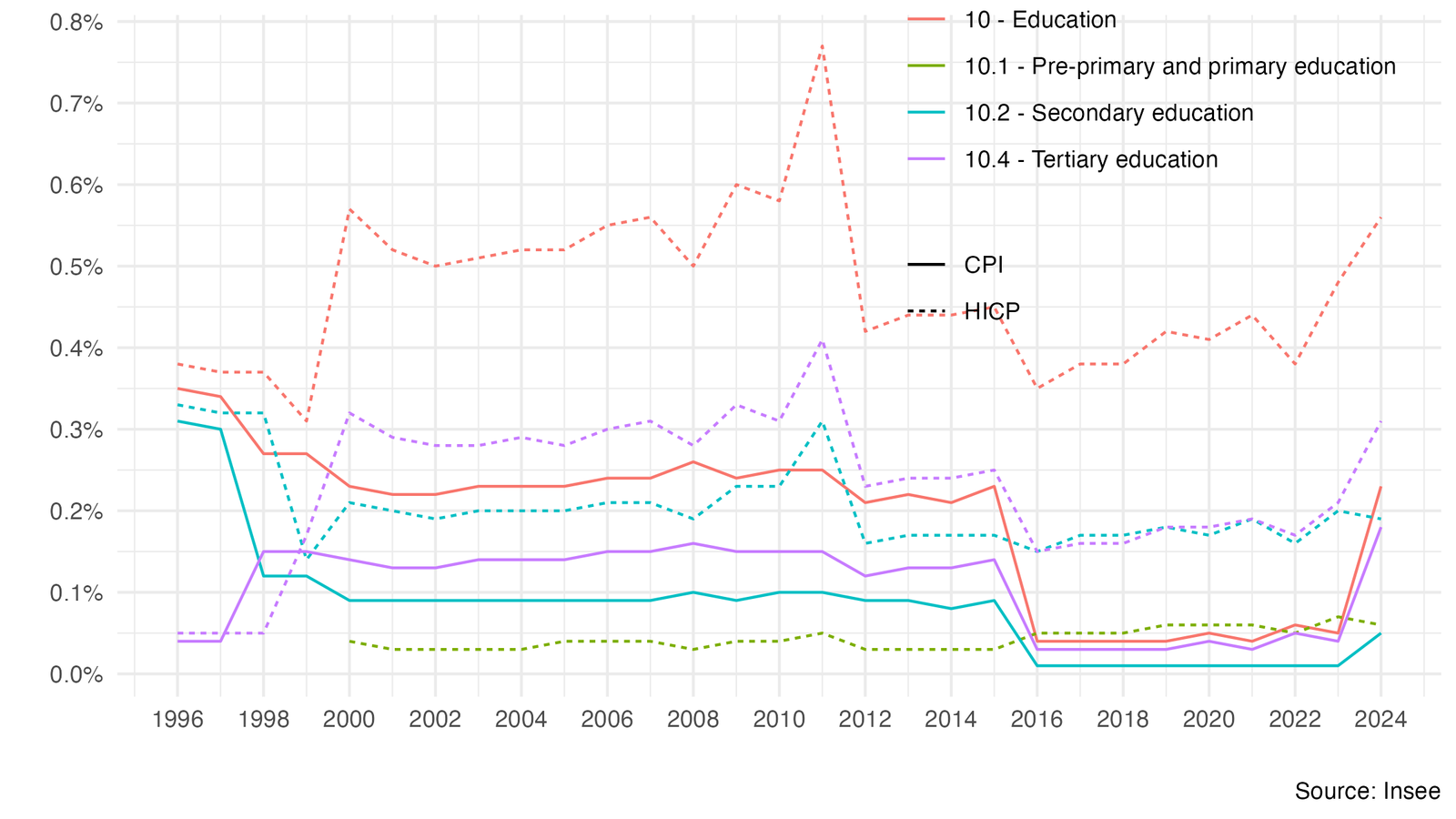

There are other, less quantitatively significant, differences between the CPI and the HICP. As mentioned by Daubaire (2022), the CPI does not include private school tuition fees, unlike the HICP (see Figure 2). This is not insignificant in a context of increasing privatization and rising tuition fees. Not mentioned by Daubaire (2022) is the presence of a “gambling” category in the CPI, but not in the HICP, represented by scratch cards for 0.9% to 1% of the index4, which leads to an understatement of CPI inflation. Finally, the abolition of the audiovisual license fee in 2022 was recorded as a price decrease for the CPI (not for the HICP), even though some households were already exempt.

A CPI methodology not compliant with international recommendations or with economic logic

This CPI approach, which consists of including reimbursed healthcare expenditures in the price index, is a French specificity that is not consistent with the recommendations of the methodological manual on price indices, produced by the World Bank, Eurostat, the IMF, the OECD, the UN, and the International Labour Organization. (Banque Mondiale et al. (2020)) These recommendations, whose legitimacy is recognized by the French statistical institute5, clearly state that only net prices should be included in a Consumer Price Index. Paragraph 11.294 on page 274 of this manual states very explicitly: “Only household expenditures directly resulting from the purchase of individual goods or services are taken into account in the consumer price index (CPI). These prices must be net of direct reimbursements.” Paragraphs 11.294, 11.296 and 11.298 go in the same direction.

From the point of view of economic logic, this is easily justified: a reduction in the price of drugs reimbursed by social security should make it possible to reduce contributions, thus increasing net wages. It is therefore not relevant to account for this price decrease twice: once via the increase in net wages, and another via the price index used to calculate real net wages. Conversely, the various cost-saving measures implemented since the first Social Security Financing Act (LFSS) for 1997, which for the first time set national targets for the growth of health insurance spending (ONDAM), particularly from 2005 onwards (such as flat-rate contributions, deductibles, and the delisting of certain drugs), mean that net wages no longer allow as much healthcare to be purchased. In calculating real net wages, it is therefore preferable to use the HICP, which reflects these growing out-of-pocket costs, rather than the CPI. We will return to this point below.

In this context, it is relevant to examine the reasons put forward by Insee when the harmonised European price index (HICP) was created and to understand why the French CPI method was not retained. For example, Barret, Bonotaux, and Magnien (2003), in Insee’s journal Économie et Statistique, write: “The ‘gross’ prices of health goods and services tracked for a long time in the CPI are tracked in ‘net’ in the HICP since January 2000. The choice between monitoring net or gross prices was extensively debated in the late 1990s, during the construction of the HICP, with member states divided on this issue. The advocates of gross prices had no shortage of arguments.” They go on to state: “The choice between a gross or net approach also has political implications at the national level. The price index indeed allows low wages to be indexed to preserve their purchasing power. With net prices tracked, the State would take back with one hand, through a smaller increase in the minimum wage, what it had given with the other, through an increase in Social Security benefits.” Since 2003, however, measures have been observed aiming to reduce the generosity of social security benefits – these delistings would have led to a larger increase in the minimum wage if net prices had been tracked.

It should also be noted that historically, Insee has not always tracked “gross” prices for healthcare. This practice of including social security reimbursements in the CPI appeared as a novelty with the 5th generation of the price index (the index of 295 items, base 1970), published in March 1971, and it has been maintained up to the current 8th generation of the price index (base 2015): “The previous indices limited healthcare services to the co-payment (net values, reimbursements deducted). Rents were net of housing allowances. These expenditures are now gross.” (Insee (1981)) For the 9th generation of the price index (base 2025), which is being prepared and will be published at the beginning of 2026, one could consider returning to the previous practice, thereby aligning with the methodology of the HICP and the recommendations of international manuals.

“Constant euro” evolutions

The price index has at least a dual function: it is used for indexations and therefore has political consequences for the distribution of income among households, as noted by Barret, Bonotaux, and Magnien (2003). It is also used to calculate so-called “constant euro” evolutions, which are supposed to take inflation into account and allow amounts in euros to be compared across two distinct dates. However, since differences exist between the two indices, using the HICP rather than the CPI has significant effects on the measurement of the purchasing power of net wages and on other published incomes.

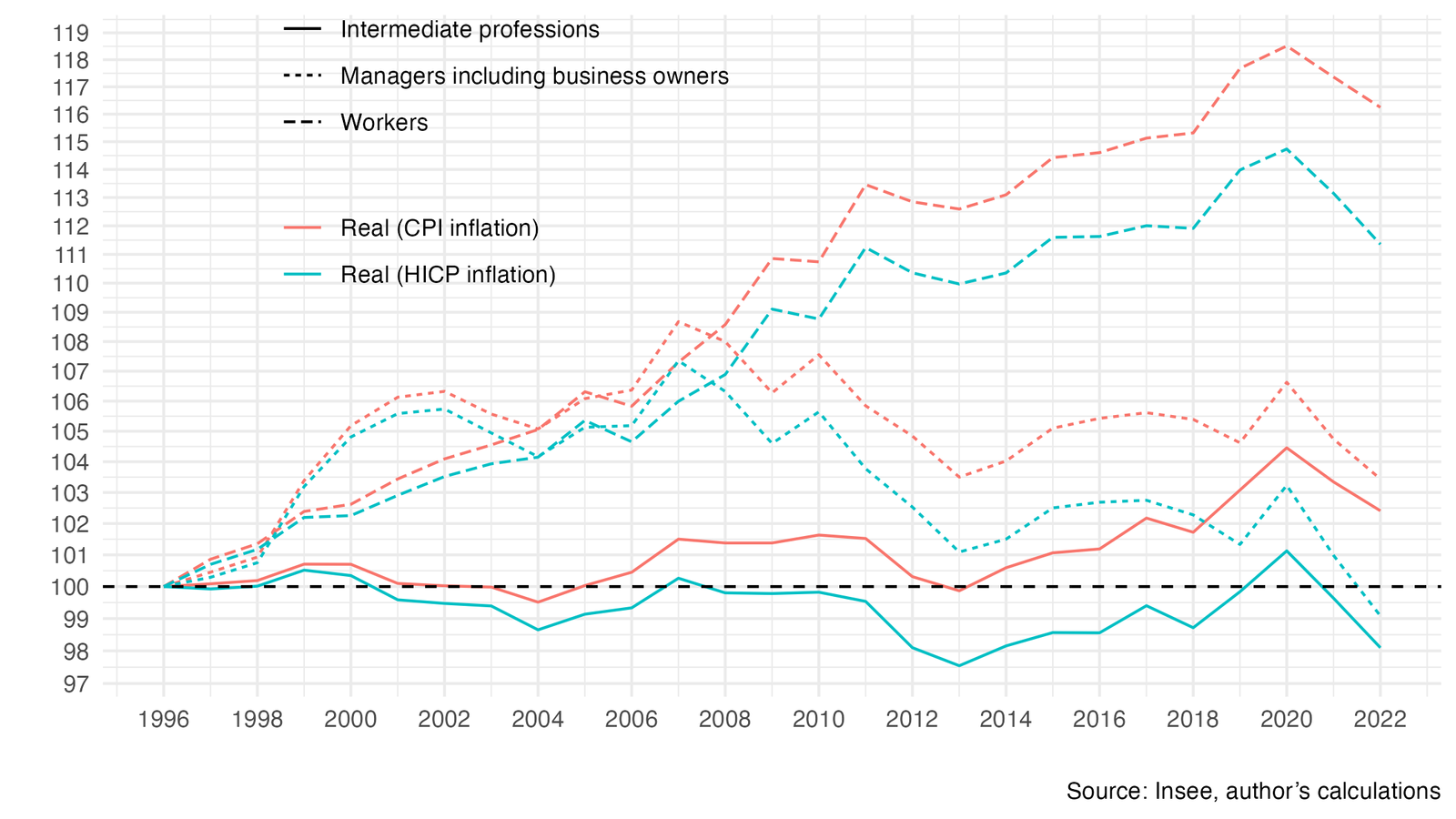

Let us take some examples to illustrate the effects on the measurement of purchasing power and net wages of using the HICP. Figure 3 shows, for instance, that the real wages of executives, including salaried company directors, decrease significantly between 1996 and 2022 when the HICP is taken into account, whereas they increase when the CPI is taken into account. This is all the more remarkable since this does not take into account the last two years of high inflation, which saw a strong erosion of real wages (even more pronounced according to the HICP).

It is also possible to redo the same calculations for the living standards published by Insee, as well as for all incomes usually published in constant euros. Another example with the civil service pay index point is given in Figure 4.

The case of the “CPI excluding tobacco”

Dares (Directorate for Research, Studies, and Statistics), the statistical service of the Ministry of Labour, publishes “constant euro” evolutions based on the CPI excluding tobacco. This method is partly dictated by the Neiertz law, which prohibits indexation on indices including tobacco prices. However, it is crucial not to confuse the question of indexations with that of calculating the purchasing power of wages and “constant euro” evolutions: in this context, it is the overall CPI that should be preferred, and indeed the HICP for the reasons mentioned in this note.

It is important to note that the fact that the statistical institute calculates a CPI excluding tobacco is explicitly discouraged by the methodological manual on price indices, paragraph 2.22 (Banque Mondiale et al. (2020)): “Finally, it should be noted that the deliberate exclusion of certain types of goods and services by political decision on the grounds that the households for whom the index is intended should not purchase these goods or services or should not be compensated for price increases of these goods and services, cannot be recommended because it exposes the index to political manipulation. For example, suppose it is decided that certain products such as tobacco or alcoholic beverages should be excluded from a CPI. It is possible that when product taxes are increased, these products are deliberately selected for higher taxes knowing that the resulting price increases would not be reflected in the CPI. Such practices are not unknown.” This is indeed what has been observed in France since 1990, with an increase in the price of tobacco of 875% between January 1990 and June 2024, compared to 81.0% for the CPI and 75.0% for the CPI excluding tobacco. However, it was the legislator who imposed the calculation of this index since 1992, and at the time Insee had to oppose the replacement of the CPI with the CPI excluding tobacco.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is important to emphasize that, although the HICP represents an improvement over the CPI, it remains insufficient to accurately assess the evolution of purchasing power, notably due to its underestimation of the role of housing (Geerolf (2022)). For monetary policy, this approach can be justified by the logic of an indicator of “monetary expenditures.” However, excluding owner-occupied housing is not suitable when it comes to measuring the purchasing power of wages or tracking “constant euro” evolutions. The majority of national CPIs in Europe, as in the rest of the world, do include owner-occupied housing – unlike France, these other countries therefore maintain a national CPI alongside the HICP for good reasons – and the inclusion of owner-occupied housing has long been planned for the HICP.

Furthermore, HICPs are not as harmonised at the European level as one might wish regarding the treatment of “quality adjustments,” even for identical goods such as imported mobile phones: quality adjustments are more pronounced in France than in Europe due to different methodologies (according to Insee itself, see references in Geerolf (2024)), which also leads to an overestimation of purchasing power gains. Here again, methodological improvements could be considered, for example on the occasion of the next base change at the beginning of 2026, both for the CPI and the HICP base 2025.

Controversies over the measurement of inflation relate both to the measurement of the object “inflation” and to the very definition of that object (Desrosières (1993)). As far as the definition is concerned, it seems that the choice of the HICP methodology instead of the CPI is, in principle, up to the statistical institute. Nothing in legislation obliges the statistical institute to calculate the CPI in the way it is currently calculated, distinct from the European index. In particular, since the current French CPI does not follow international recommendations, the French statistical institute could choose to align with the HICP methodology for indexations. In the short term, it is recommended to use the HICP rather than the CPI or the CPI excluding tobacco to calculate “constant euro” evolutions of various incomes.

Bibliography

Footnotes

A first version of this text was presented on February 1, 2022, at the OFCE, for inclusion in Policy Brief No. 104 of March 17, 2022, dealing with the evolution of purchasing power in the context of the 2022 presidential elections, but was not retained in the final version of that Policy Brief No. 104. The divergences between the CPI and the HICP are mentioned on page 2 of the note of February 22, 2022, addressing the inclusion of housing prices in inflation measurement by Insee (Geerolf (2022)). On March 1, 2022, Insee published a blog on the differences between the CPI and the HICP (Daubaire (2022)). A Github repository allows replication of the results from source data, and additional charts are available here.↩︎

According to Insee, “The HICP does not replace the national index, which remains the reference index for analyzing inflation in France.” See: https://www.insee.fr/fr/metadonnees/source/indicateur/p1654/description↩︎

One exception exists to this rule (for a tax, and not for income): cadastral rental values, used to calculate the property tax, are revalued according to HICP inflation, which is higher, rather than according to CPI inflation.↩︎

Thanks to the association “Ouvre-boîte” and a decision by the administrative court, Insee now provides the list of varieties and weights. For more on this procedure, see here.↩︎

For example, in this Insee blog: “The methodology of the CPI results primarily from the work and decisions of national experts and international organizations. Insee’s choices are not specific to France: at the international level there is a methodological manual produced by all these organizations, and at the European level a regulation that define how to calculate the CPI.” (Ourliac (2020))↩︎