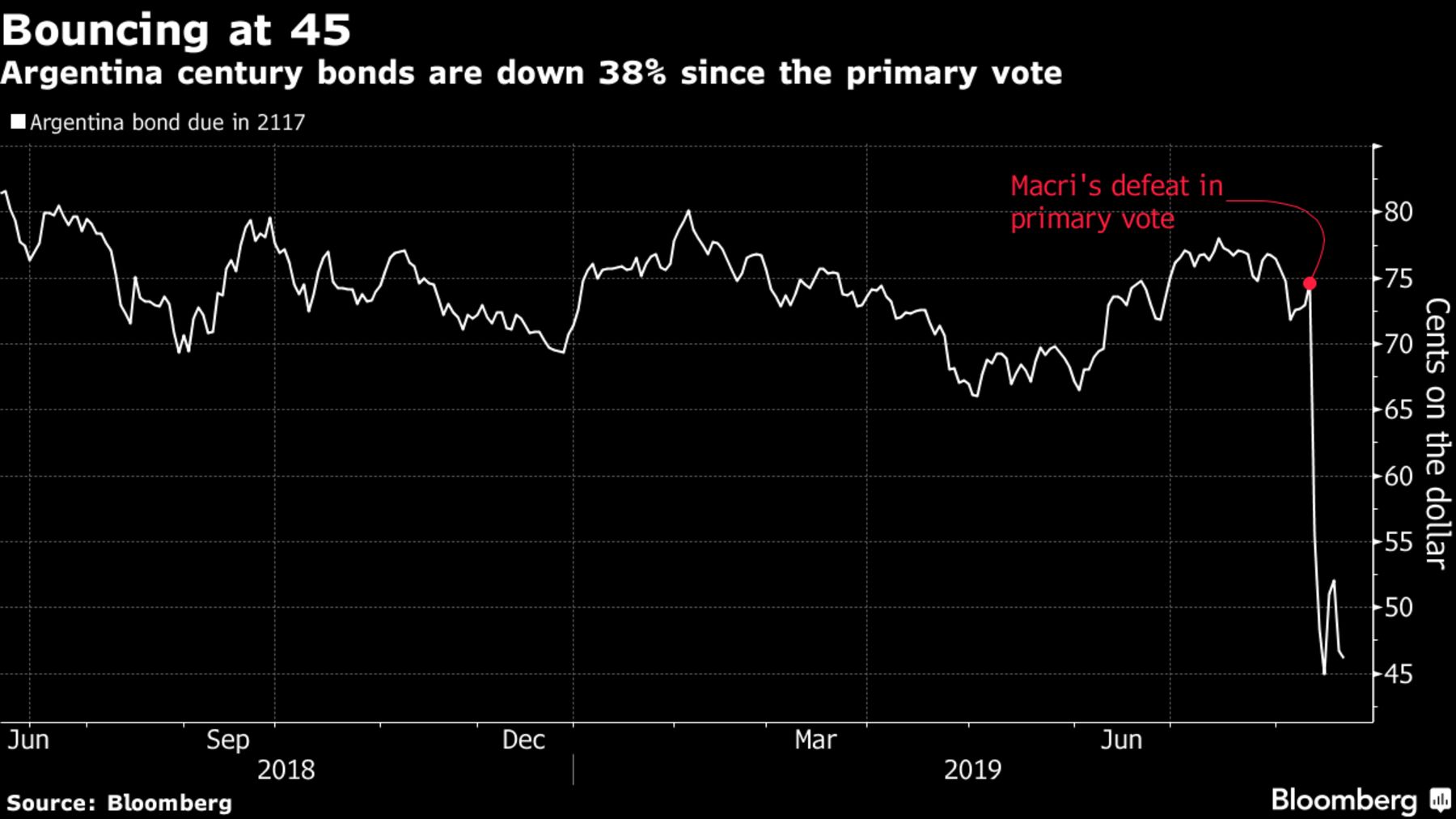

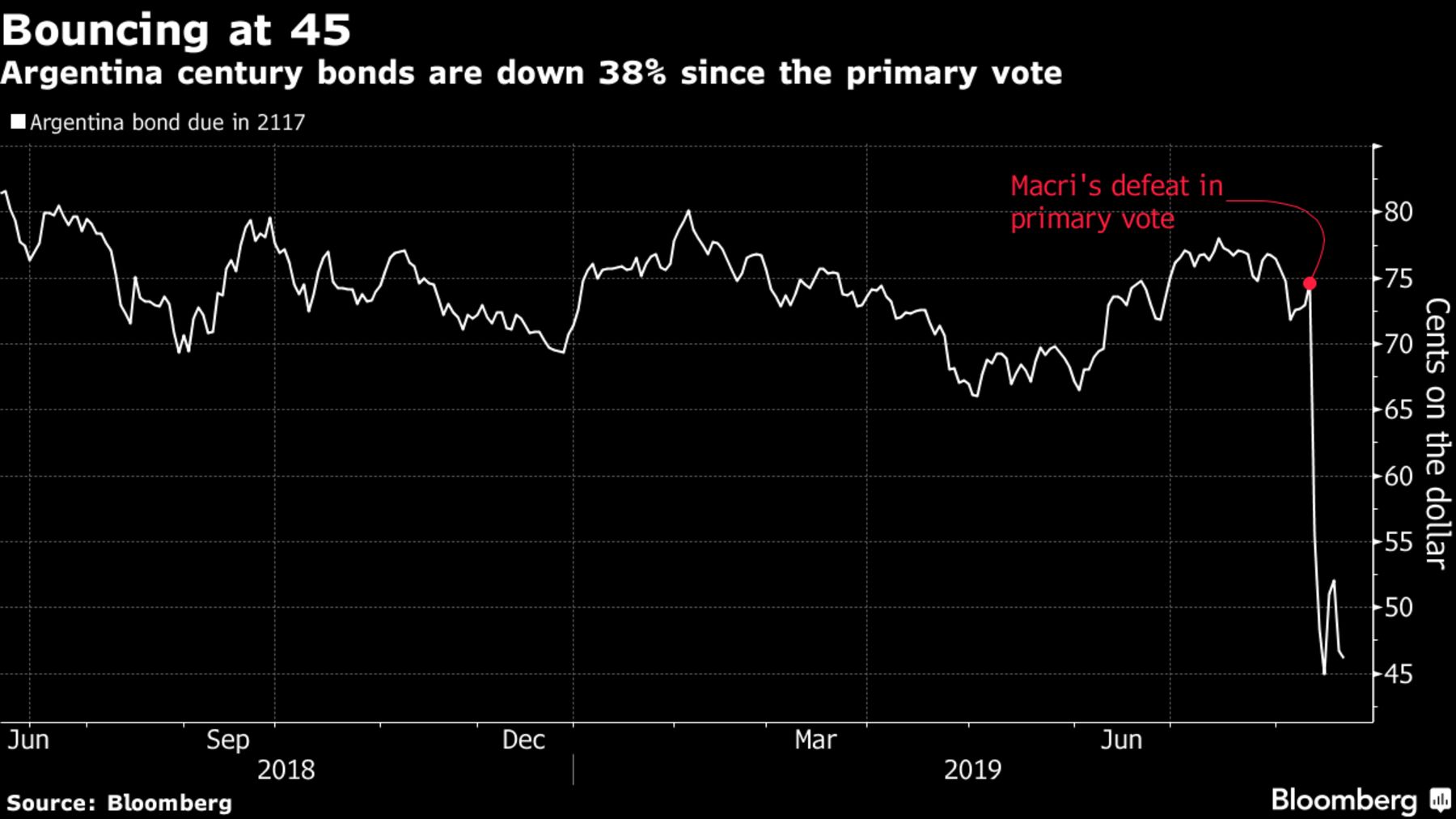

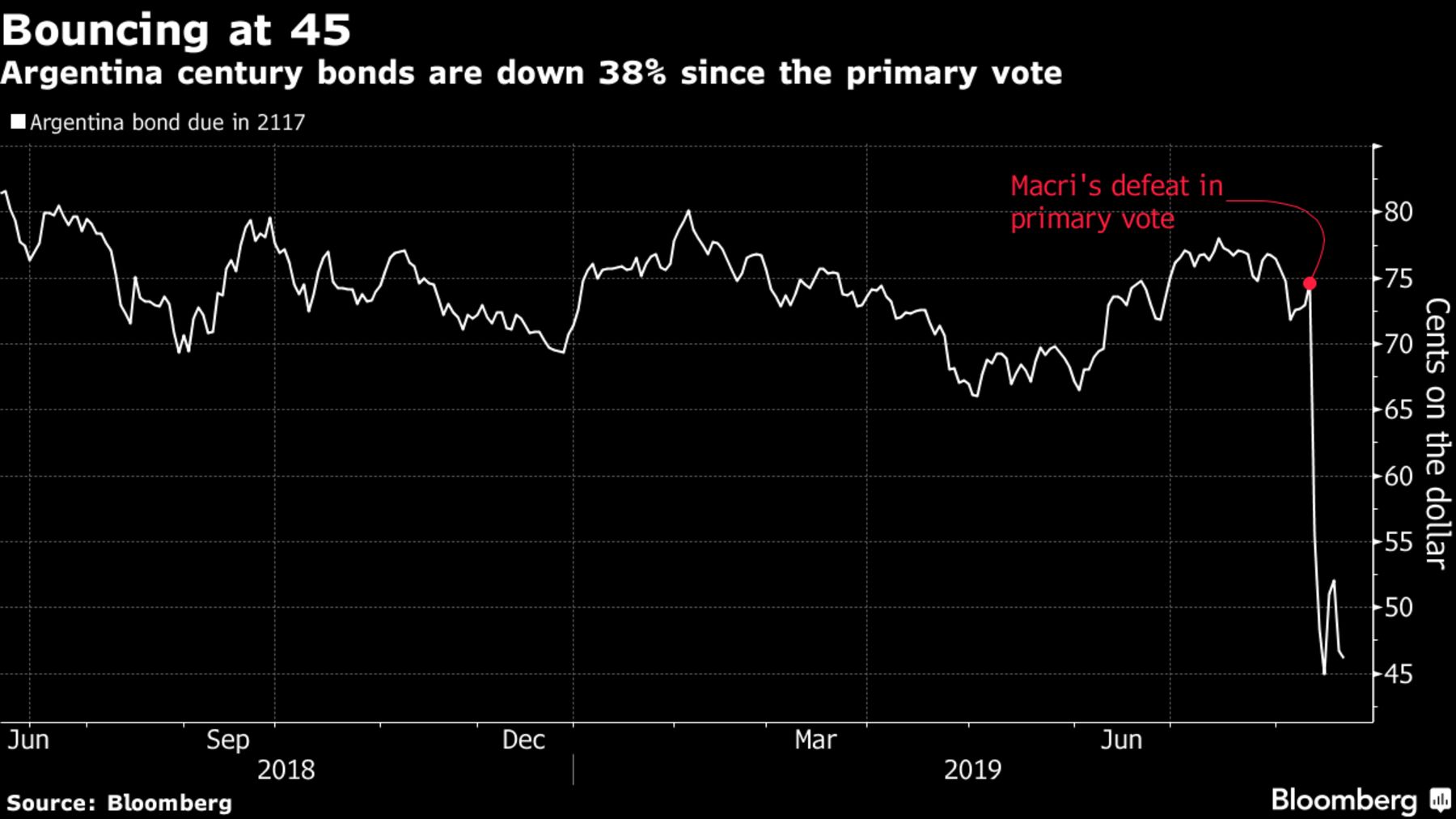

Primary Vote in Argentina

There are several versions of these slides:

Before you read these, here’s some undergraduate material relating to the topic covered in this lecture:

Own Research. Asset Pricing.

-If you are a financial economist, there are many things they don’t tell you about macro.

Schematically, macroeconomics is (not that) good at explaining quantities, but very bad at predicting prices.

Symmetrically, finance is (not that) good at explaining prices, but fares terrible to predict quantities.

The two types of explanations are usually inconsistent: you need high elasticities for macroeconomics to explain why quantities move a lot. (people should not be very risk averse for instance) However, you need low elasticities to explain why prices move so much.

“valuations are completely based on momentum and inflows and the more money that’s flowing into something the more valuable it gets, and it doesn’t really matter things like price/book or other measures of fundamentals.”

“Anything related to valuation doesn’t matter for traders.”

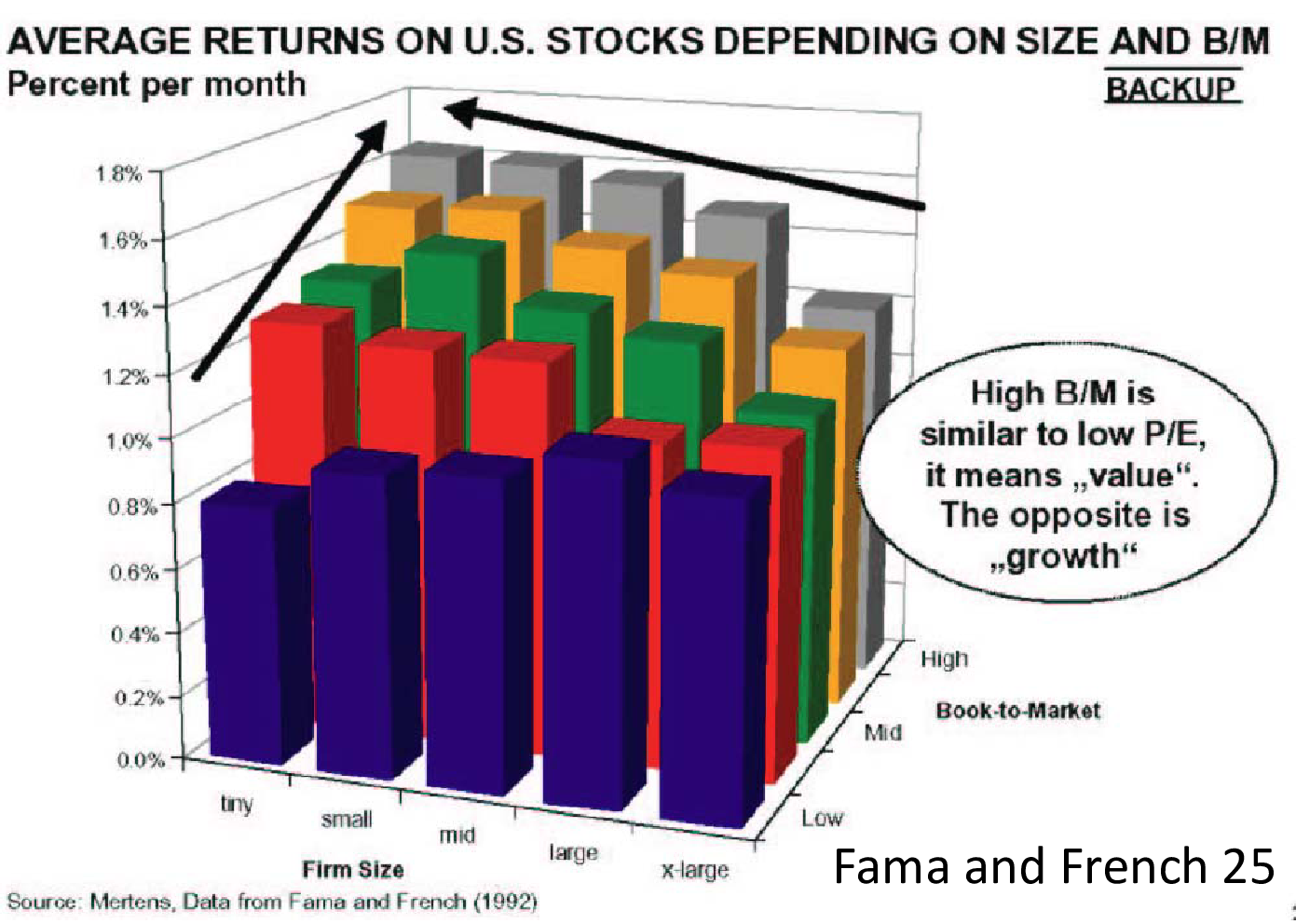

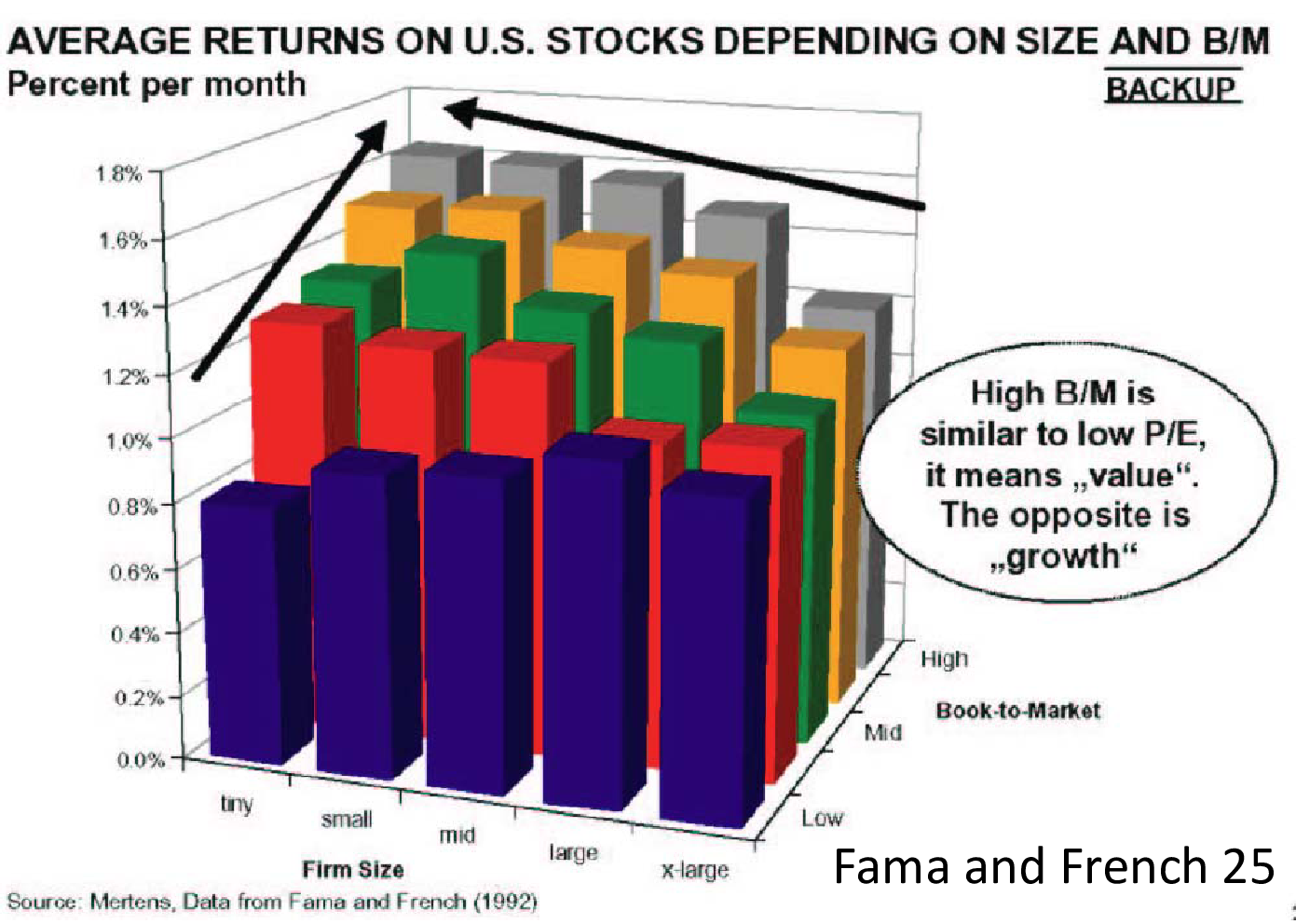

Very little role for \(\beta\).

Other factors predict returns: Book to Market, Size.

They are related to “risk factors” according to Fama, French; but here “risk factors” mean: if you are more correlated to them, you have higher returns.

So it’s just a way of relabeling puzzles, in a theory-consistent way.

My view is there is really no evidence in favor of the CAPM, or even in favor of the risk-return model.

There are many readings attached to this lecture, mostly coming from The Economist magazine.

This is (again) one of my pet theories (the title of my Ph.D. dissertation was “Bubbles and Asset Supply”). It is not universally accepted in the profession, although it is probably more popular in the investment community. Again, there are many controversies in economics, and whether “rational bubbles” are a possibility is one.

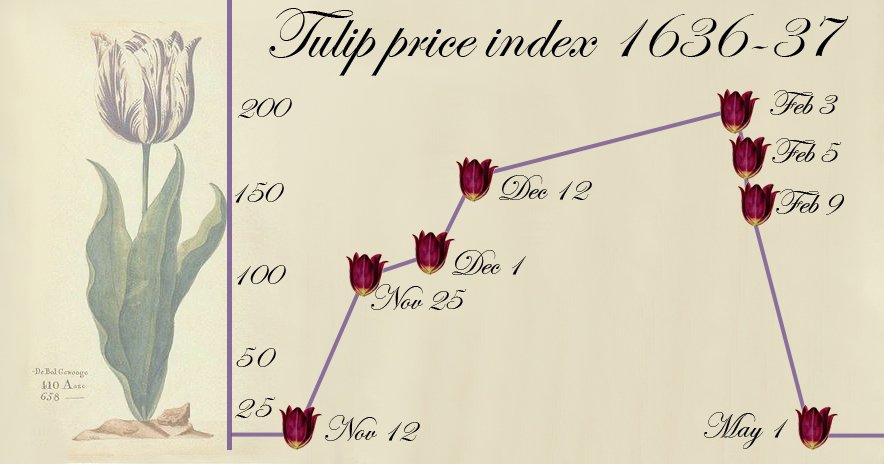

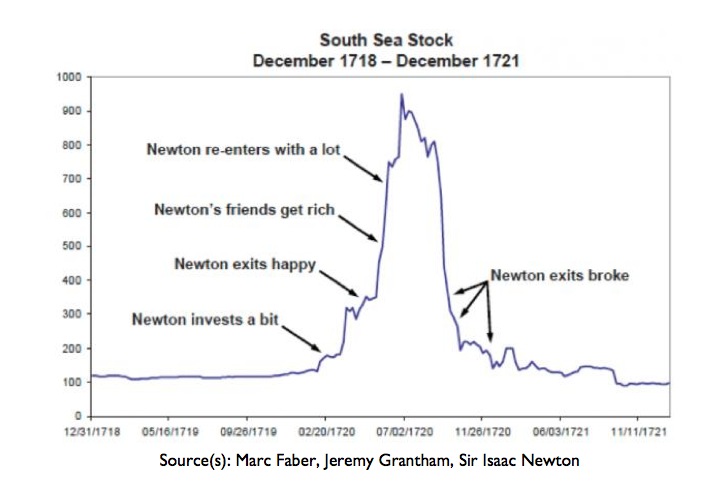

“Rational bubbles” sounds like an oxymoron:

“Bubbles” usually refer to something irrational, perhaps even stupid. Robert Shiller: “irrational exuberance.”

There is some reason why people buy overvalued assets, they are not being “stupid.” Low rates and high returns: the “bull market in everything.”

There is a view in finance called “efficient markets.”

Indeed, there are many arbitrage relationships which are satisfied on financial markets. This does not imply that financial markets are efficient. Larry Summers (1985) once mocked finance professors likening financial economics to ketchup economics: “Nonetheless ketchup economists have an impressive research program, focusing on the scope for excess opportunities in the ketchup market. They have shown that two quart bottles of ketchup invariably sell for twice as much as one quart bottles of ketchup except for deviations traceable to transactions costs and conclude from this that the ketchup market is perfectly efficient.”

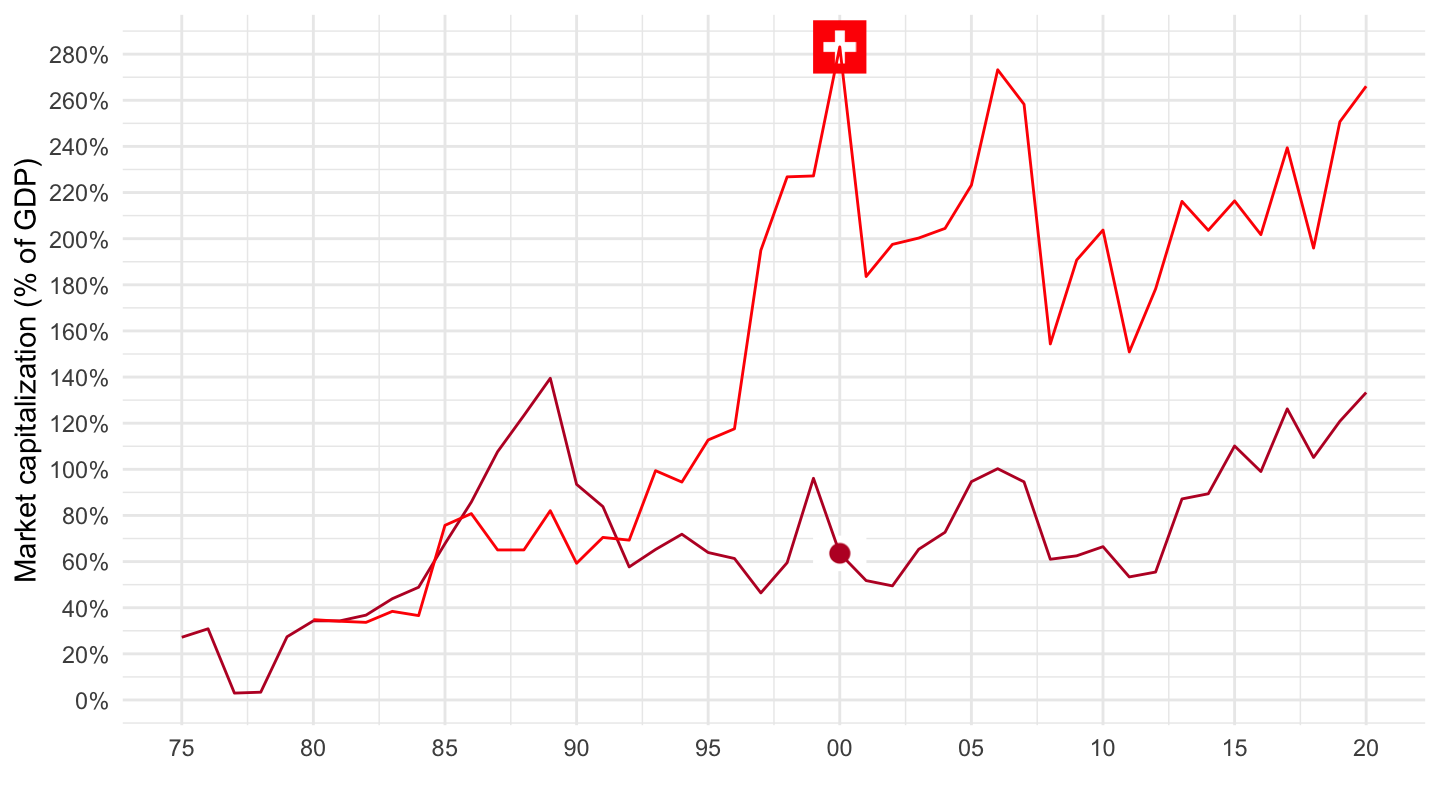

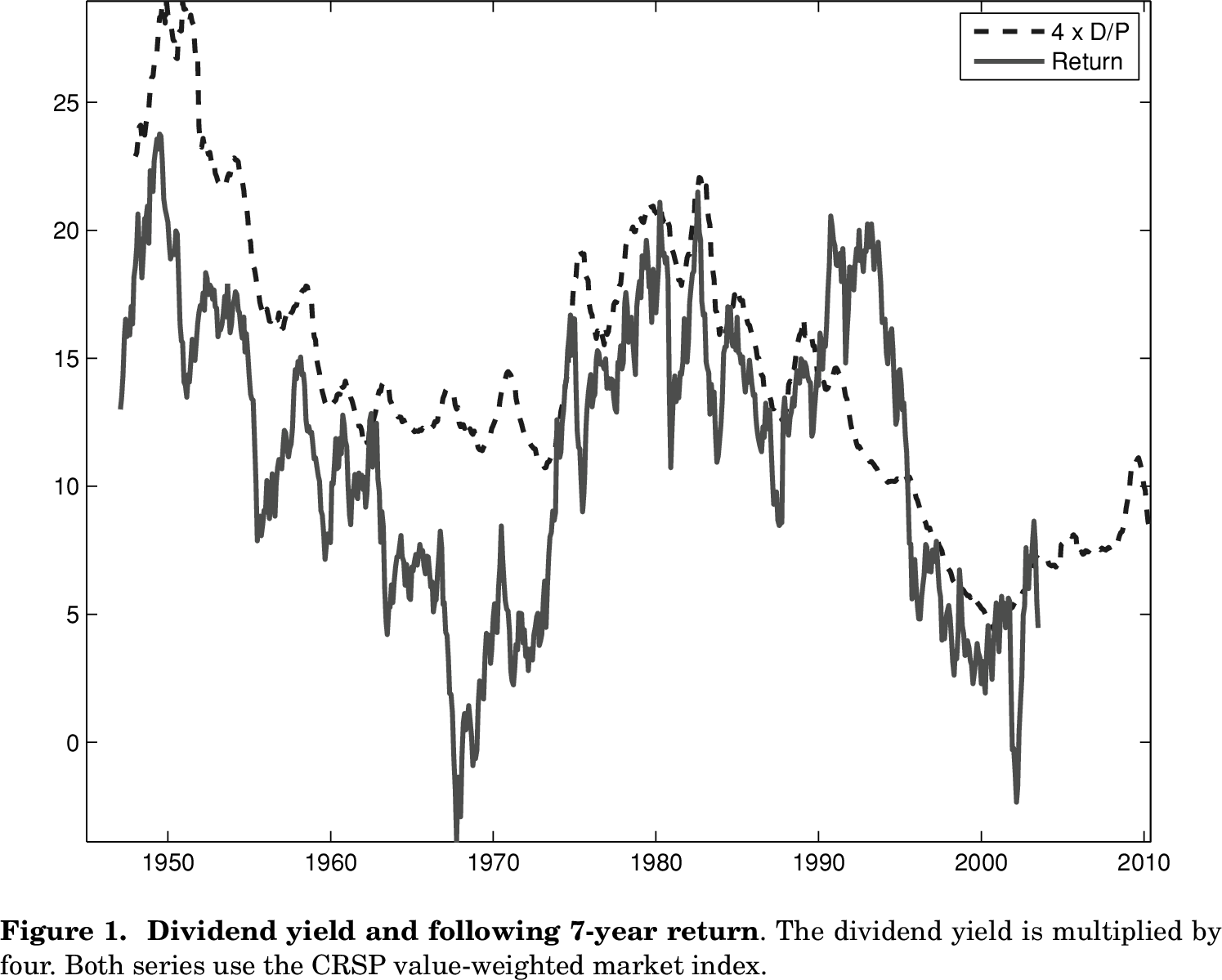

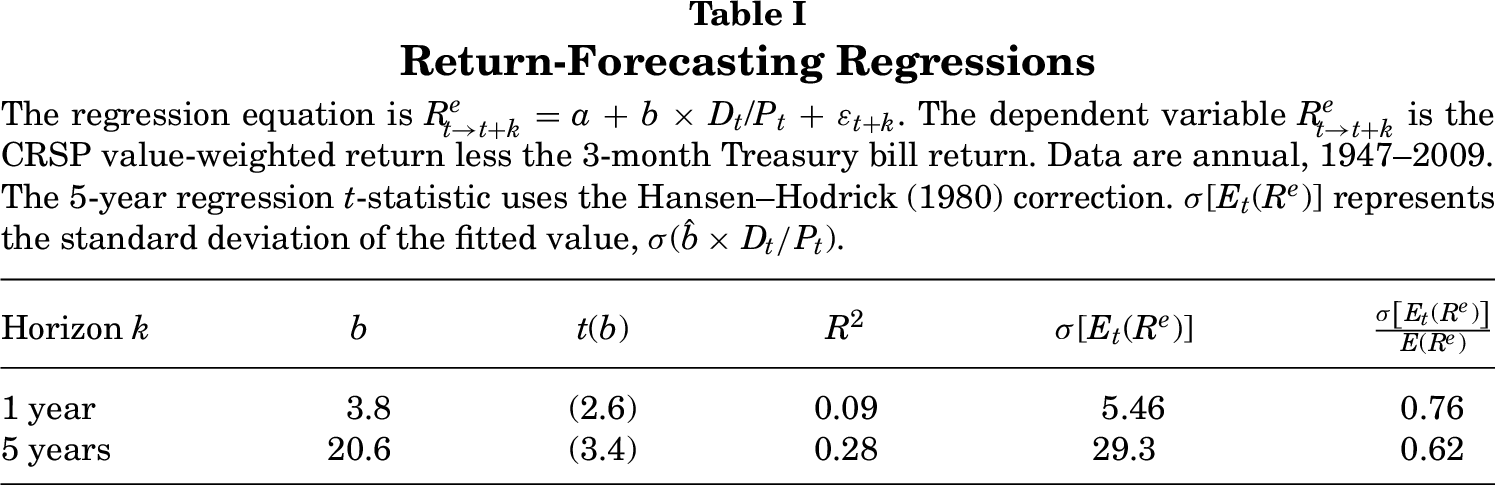

It is very hard to make sense of the huge fluctuations in stock prices, using “fundamentals” (the discounted sum of dividends)

It is also very hard to explain why the so-called equity premium is so high: why equities have done so well (in the U.S.) compared to bonds.

So in my view, there is ample room for “rational bubbles.”

Reading: “Should egalitarians fear low interest rates?” The Economist, July 11, 2019.

Keynes thought that a “savings glut” would lead to lower rates of return on capital, and erode investors’ bargaining power.

The end result should be the “euthanasia of the rentier”.

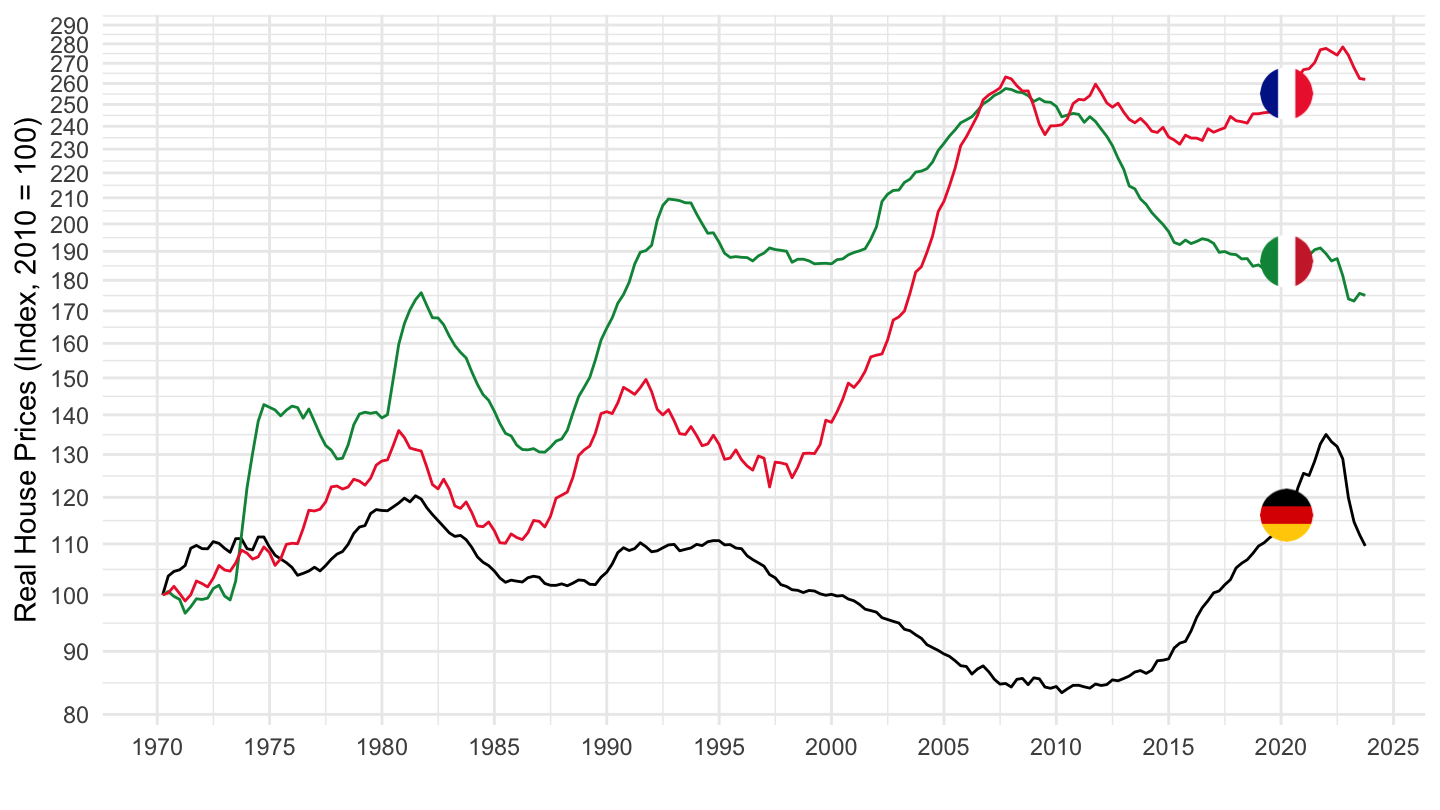

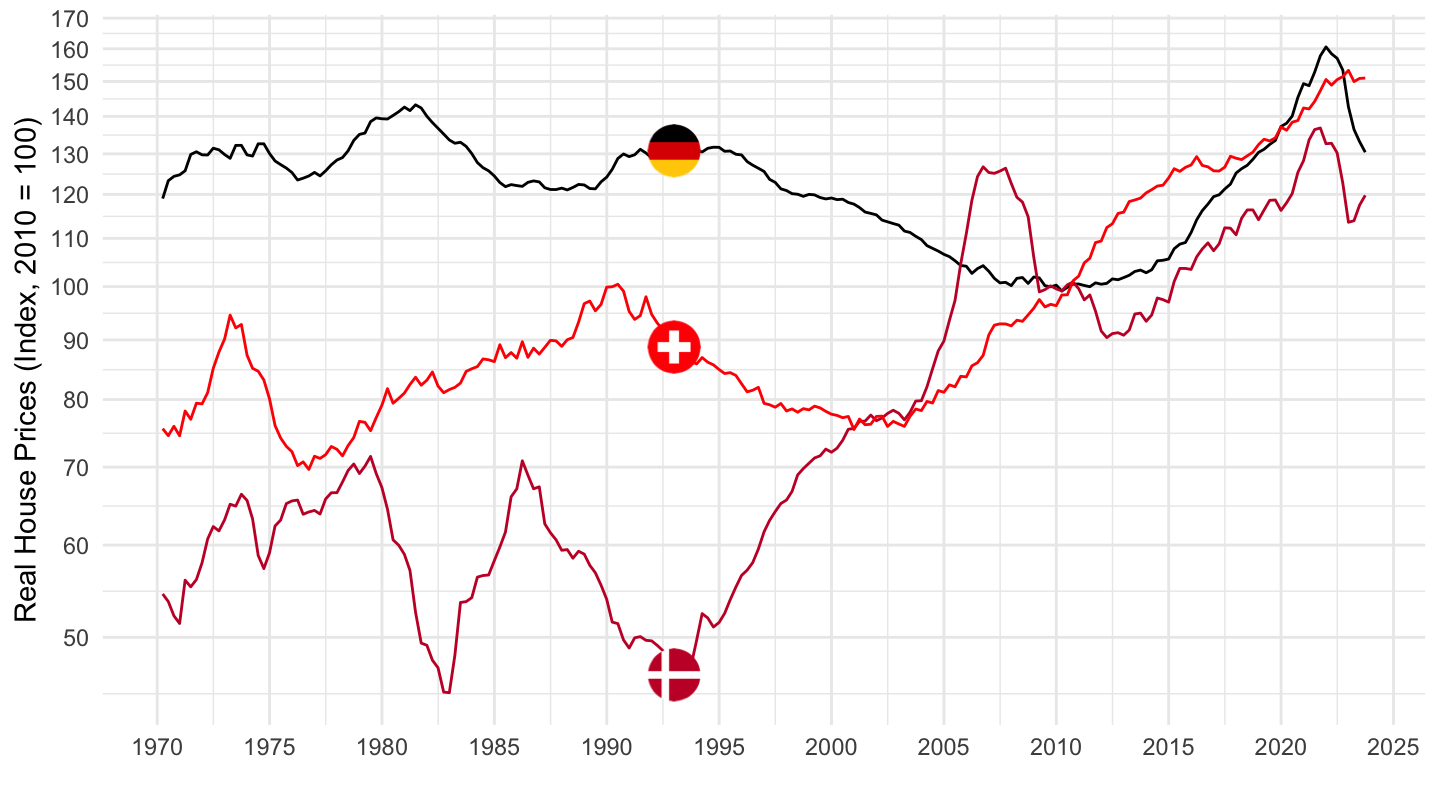

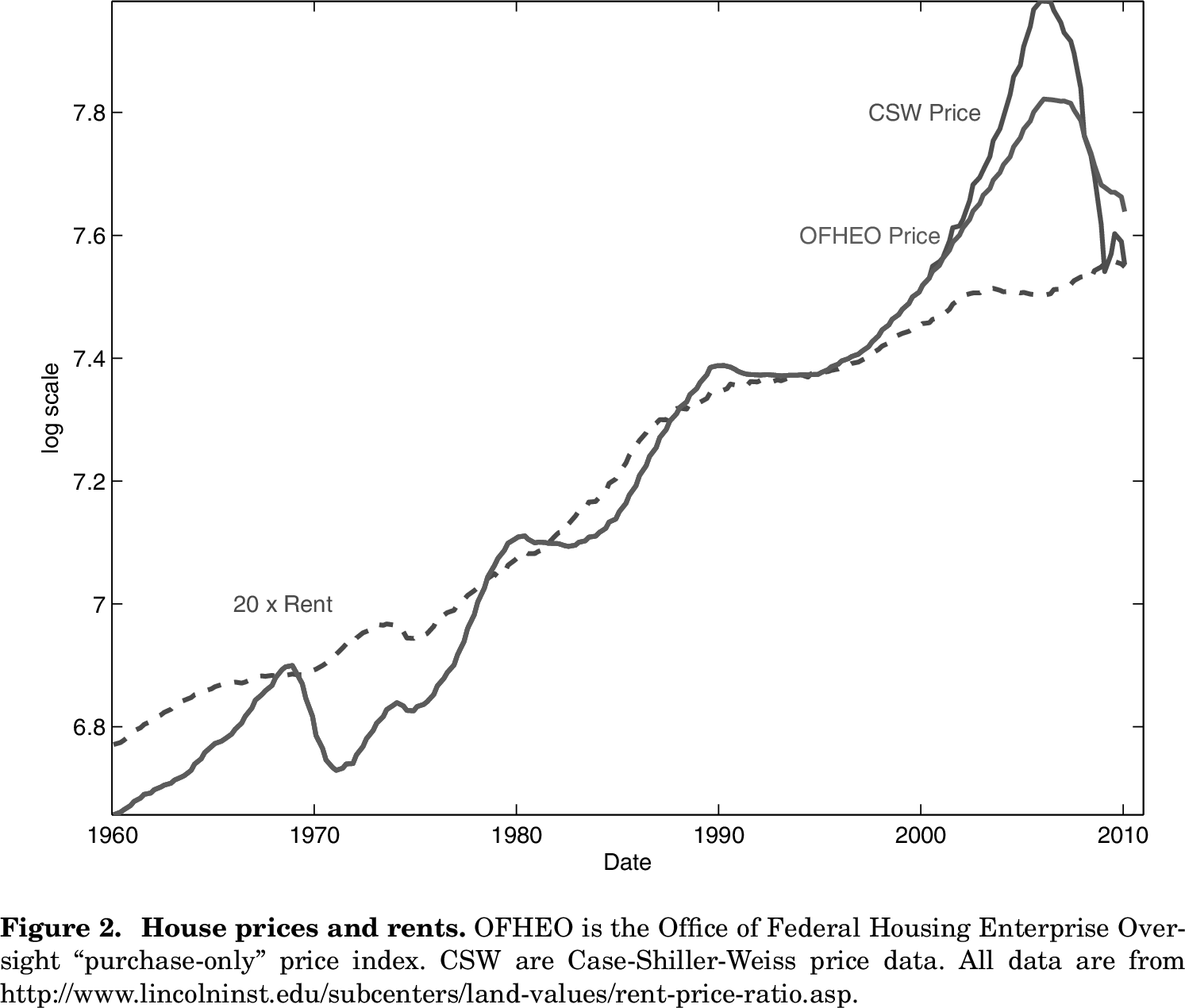

Recent episode of low interest rates suggests that in fact, they lead to soaring stock and real estate markets, thereby exacerbating wealth inequality. Therefore, when interest rates go down, the return on existing assets potentially goes up.

J.M. Keynes was indeed missing the potential for “rational bubbles”: as interest rates would become lower than \(g\), asset prices and real estate prices could potentially become overvalued, maintaining and even boosting the returns of the investor class, even as interest rates stayed low.

In the lecture on overlapping-generations models, we have seen that savings glut are a possibility when interest rates are low.

As The Economist explains, the corresponding boost in house prices has also added to substantial intergenerational tension, as this corresponds to a transfer from the “young” to the “old” generation (#okboomer).

This can also explain why banks lent so much: there was no other game in town.