December 6, 2020

Rational “Bubbles” for Infinite Assets

Presentation

There are many readings attached to this lecture, mostly coming from The Economist magazine.

This is (again) one of my pet theories - the title of my Ph.D. dissertation was “Bubbles and Asset Supply” (Geerolf, 2013). It is not universally accepted in the profession, although it is probably more popular in the investment community. Again, there are many controversies in economics, and whether “rational bubbles” are a possibility is one.

“Rational bubbles” sounds like an oxymoron:

“Bubbles” usually refer to something irrational, perhaps even stupid. Robert Shiller: “irrational exuberance.”

There is some reason why people buy overvalued assets, they are not being “stupid.” Low rates and high returns: the “bull market in everything.”

Financial economics

There is a view in finance called “efficient markets.”

Indeed, there are many arbitrage relationships which are satisfied on financial markets. This does not imply that financial markets are efficient. Larry Summers (1985) once mocked finance professors likening financial economics to ketchup economics: “Nonetheless ketchup economists have an impressive research program, focusing on the scope for excess opportunities in the ketchup market. They have shown that two quart bottles of ketchup invariably sell for twice as much as one quart bottles of ketchup except for deviations traceable to transactions costs and conclude from this that the ketchup market is perfectly efficient.”

It is very hard to make sense of the huge fluctuations in stock prices, using “fundamentals” (the discounted sum of dividends)

It is also very hard to explain why the so-called equity premium is so high: why equities have done so well (in the U.S.) compared to bonds.

So in my view, there is ample room for “rational bubbles.”

Low rates lead to high returns?

Reading: “Should egalitarians fear low interest rates?” The Economist, July 11, 2019.

Keynes thought that a “savings glut” would lead to lower rates of return on capital, and erode investors’ bargaining power.

The end result should be the “euthanasia of the rentier”.

Recent episode of low interest rates suggests that in fact, they lead to soaring stock and real estate markets, thereby exacerbating wealth inequality. Therefore, when interest rates go down, the return on existing assets potentially goes up.

Rational bubbles: the missing link?

J.M. Keynes was indeed missing the potential for “rational bubbles”: as interest rates would become lower than \(g\), asset prices and real estate prices could potentially become overvalued, maintaining and even boosting the returns of the investor class, even as interest rates stayed low. In the lecture on overlapping-generations models, we have seen that savings glut are a possibility when interest rates are low.

As The Economist explains, the corresponding boost in house prices has also added to substantial intergenerational tension, as this corresponds to a transfer from the “young” to the “old” generation (#okboomer).

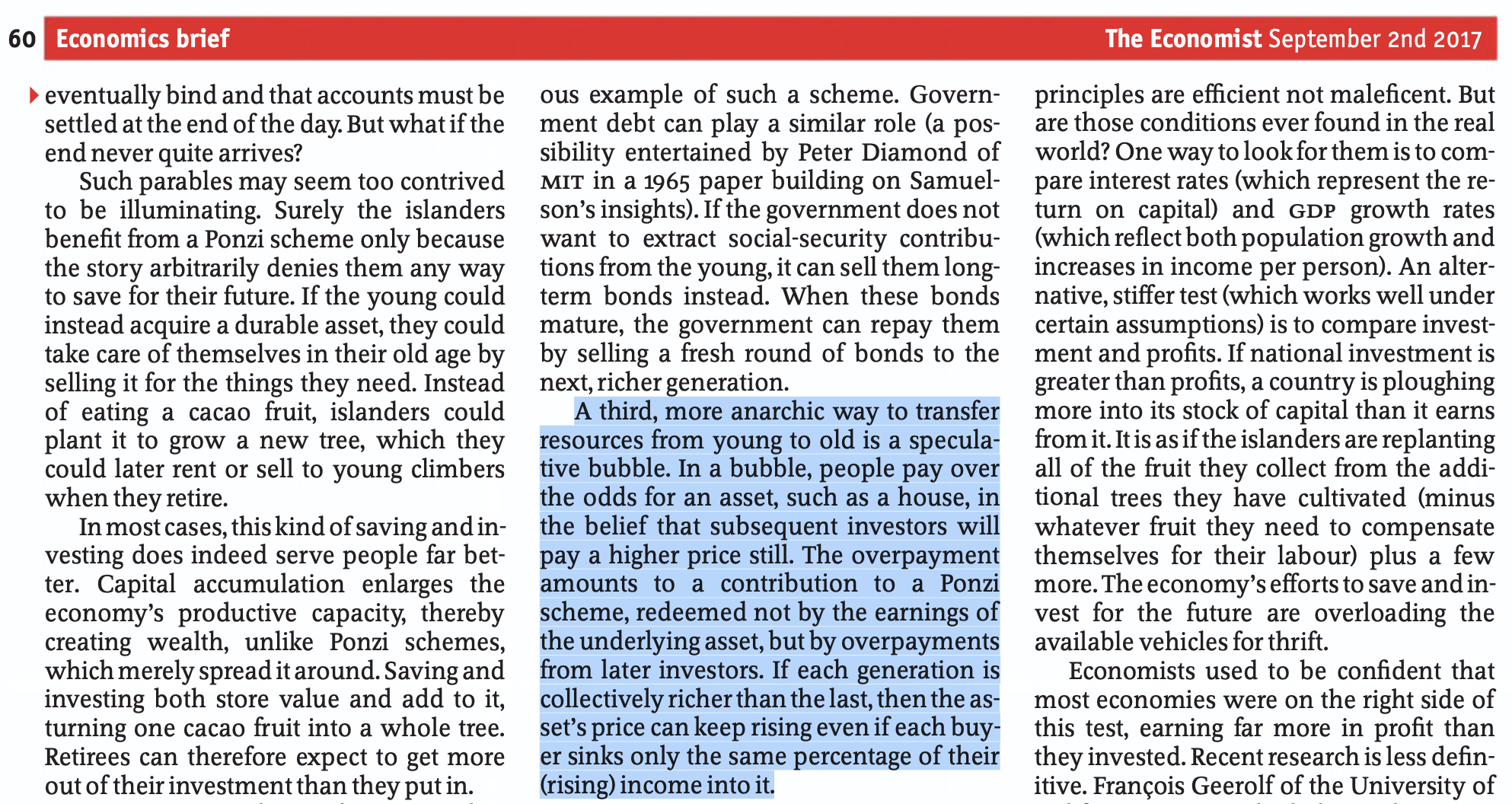

The Economist article: “Kicking down the road down an endless road,” The Economist, September 2, 2017. This can also explain why banks lent so much: there was no other game in town.

Kicking down the road down an endless road

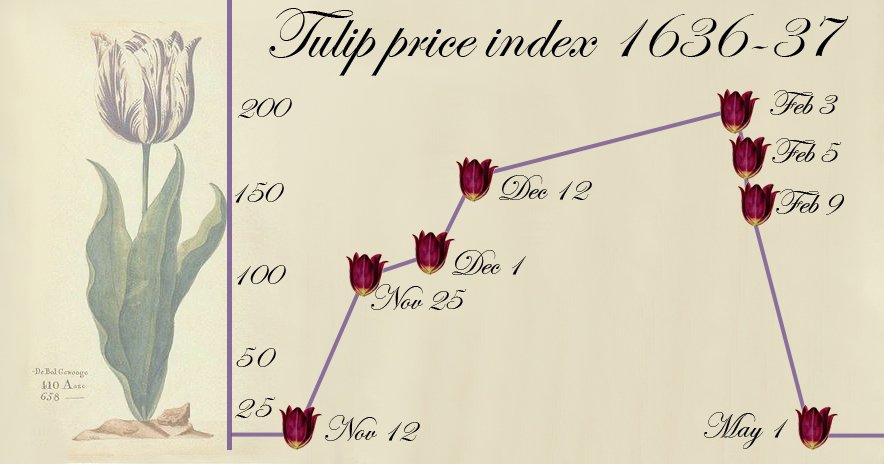

First Bubble: Tulip Bubble

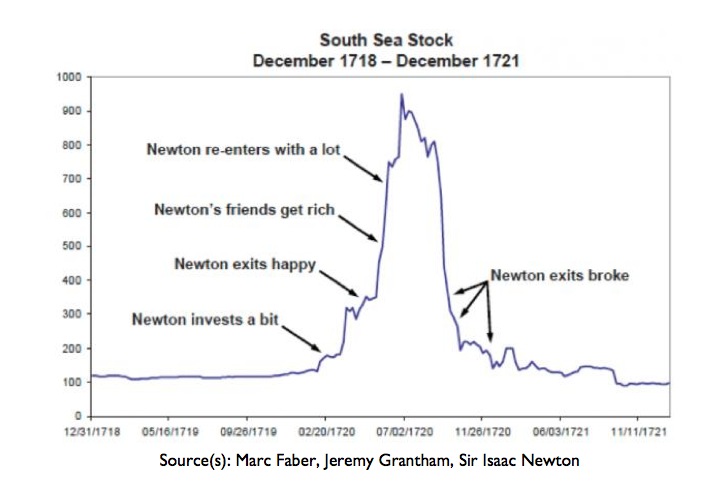

South Sea Bubble

2001 Internet “Bubble”: IPO of Pets.com

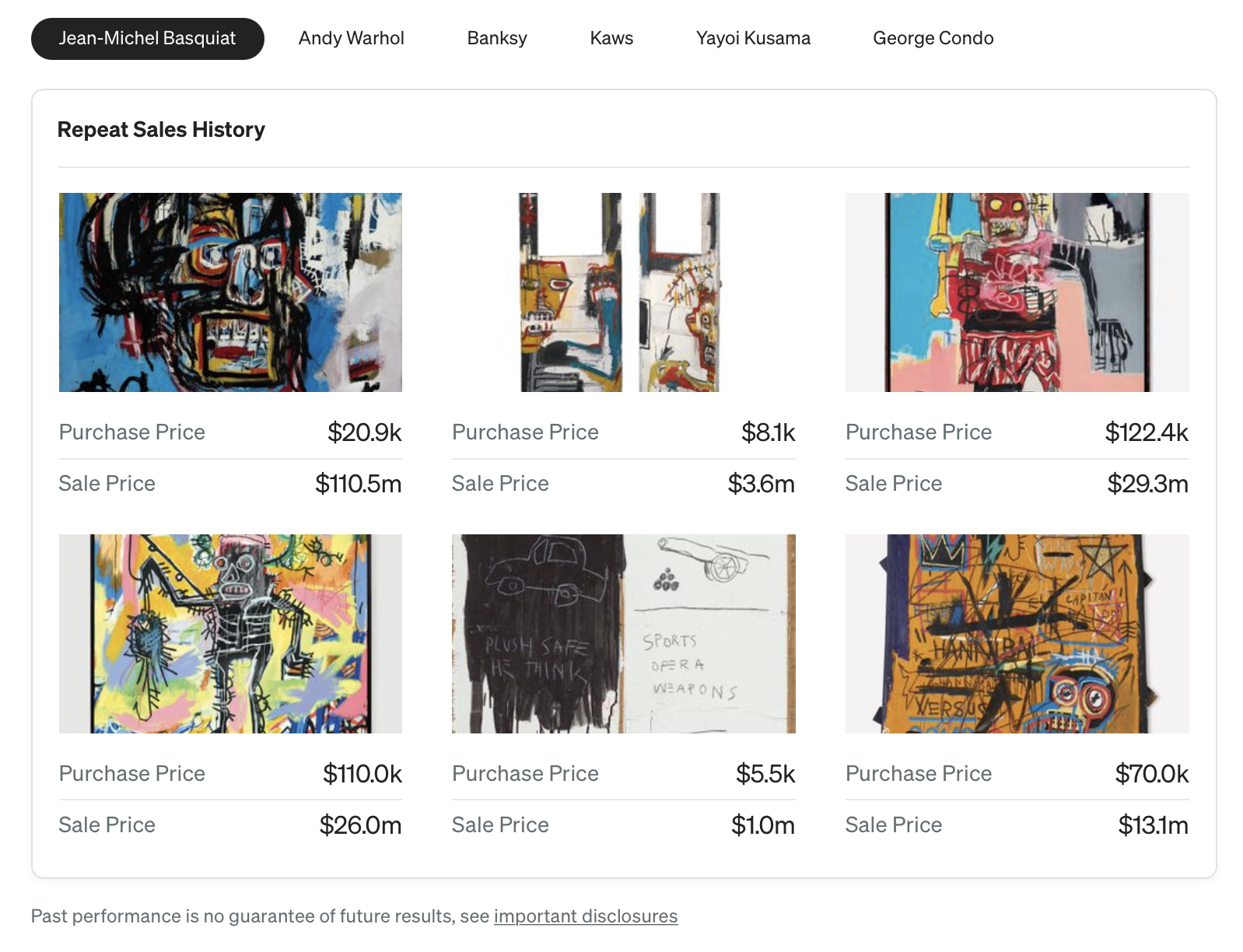

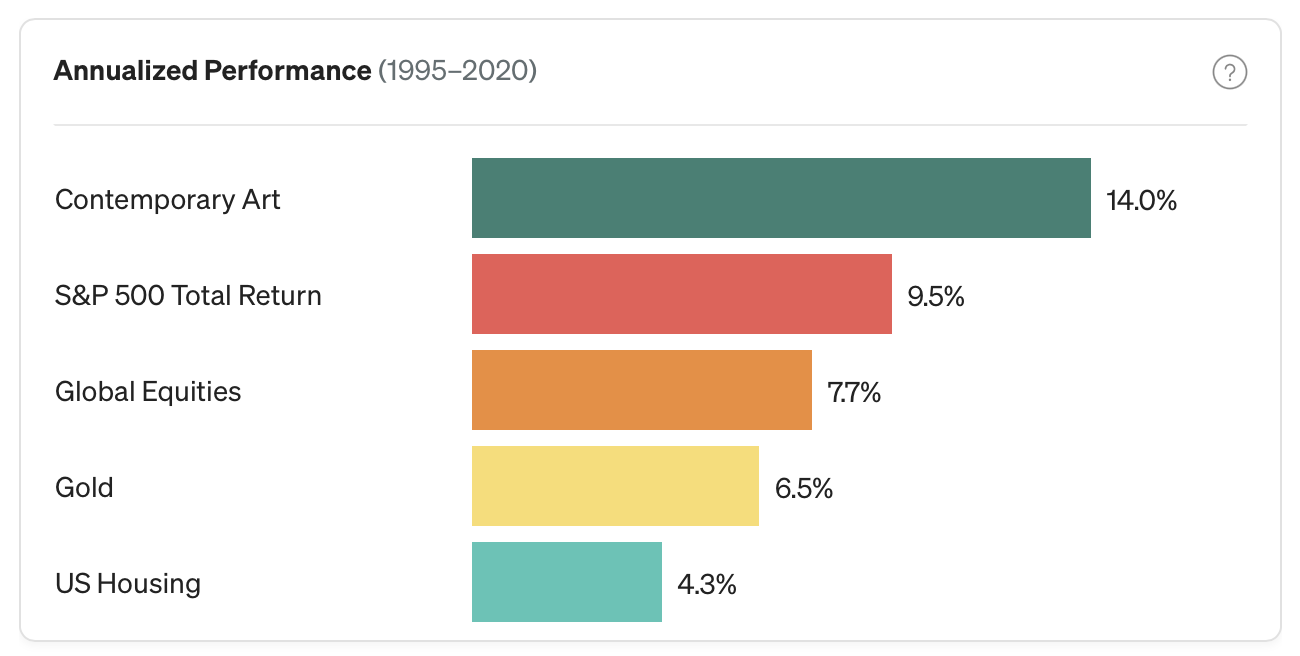

## Art as a store of value ?

## Art as a store of value ?

S&P 500, Art, Real Estate, Gold

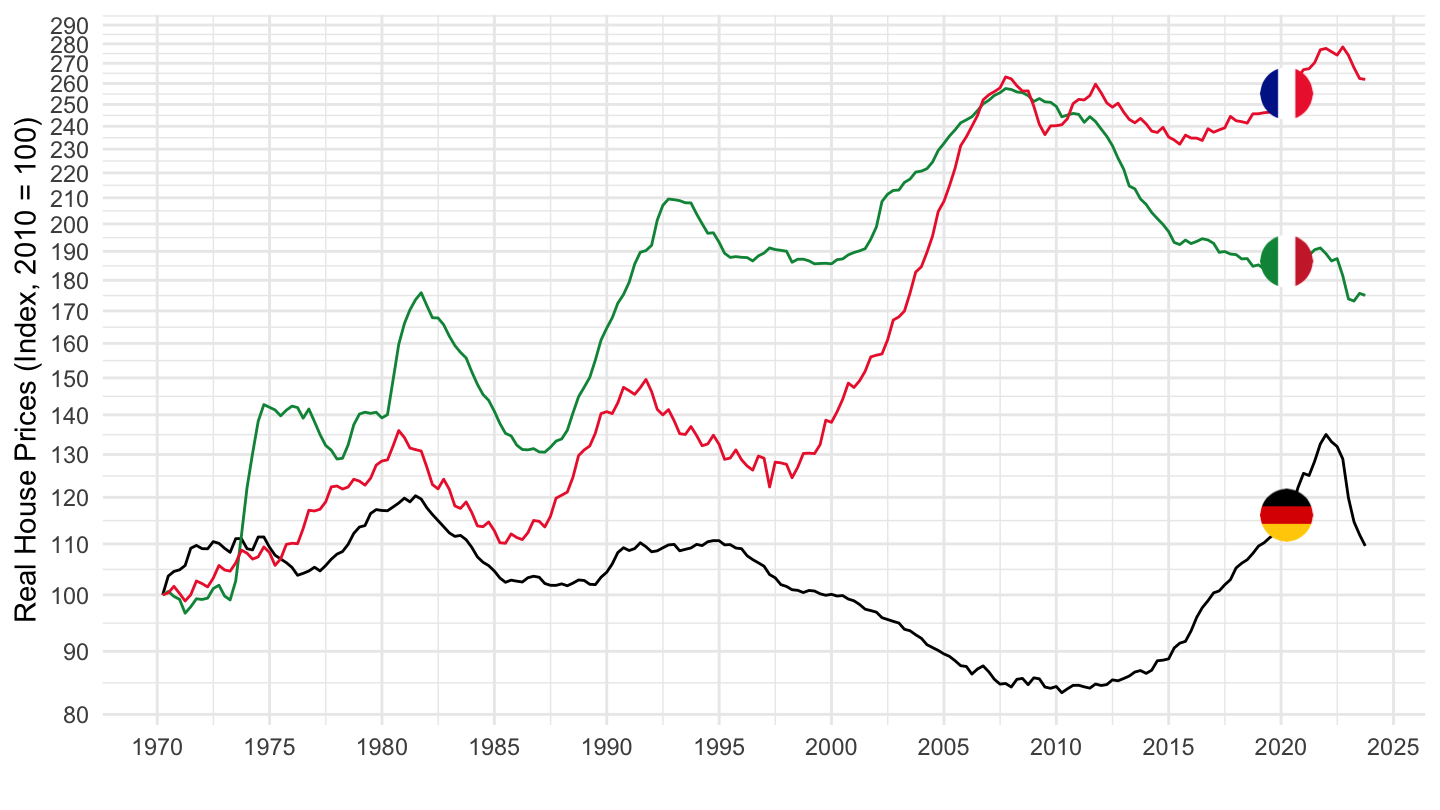

Some Data on House Price “Bubbles”

Japan, United States, United Kingdom

Germany, France, Italy

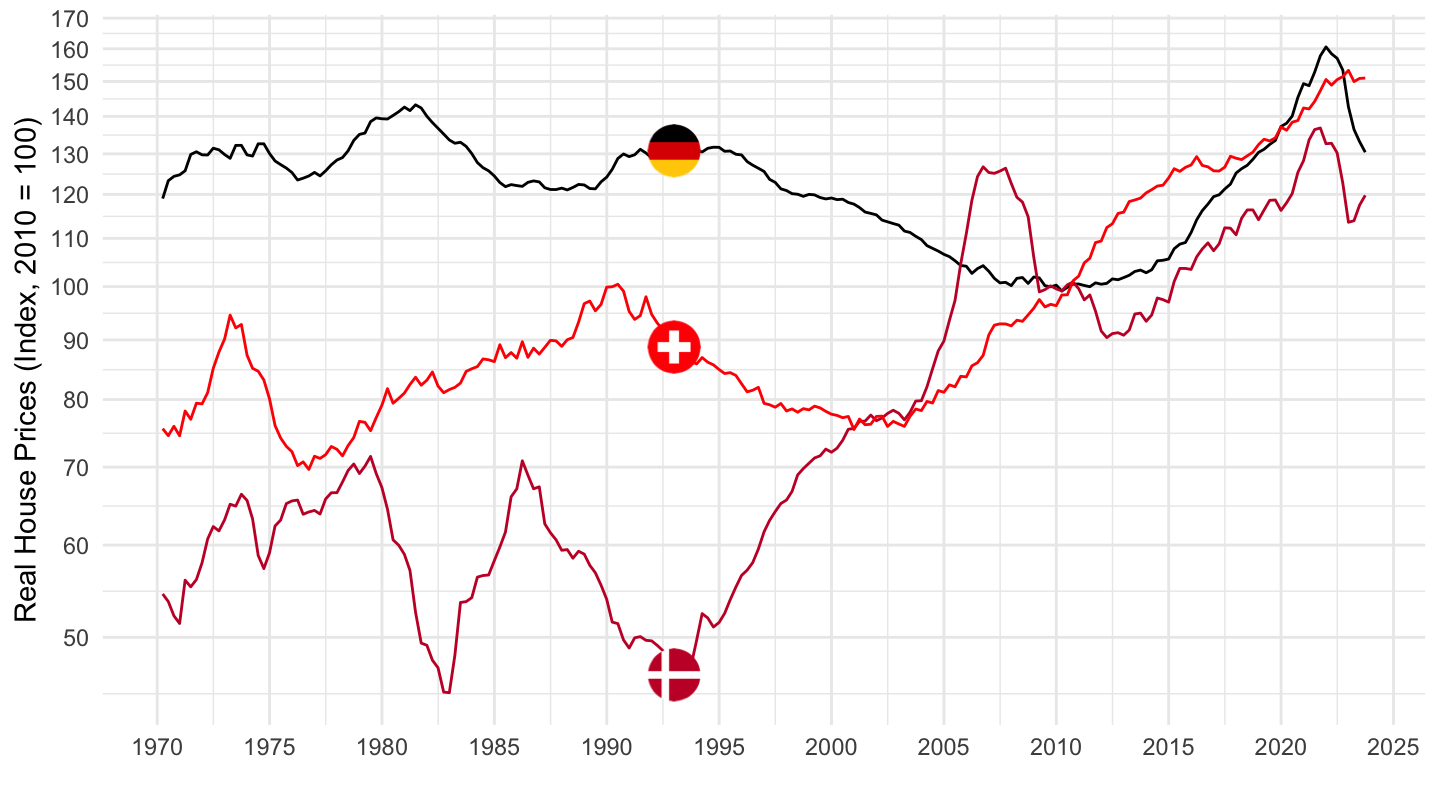

Denmark, Germany, Switzerland

In the U.S., house prices are back

Stock Price “Bubbles” - Data on Stock Prices

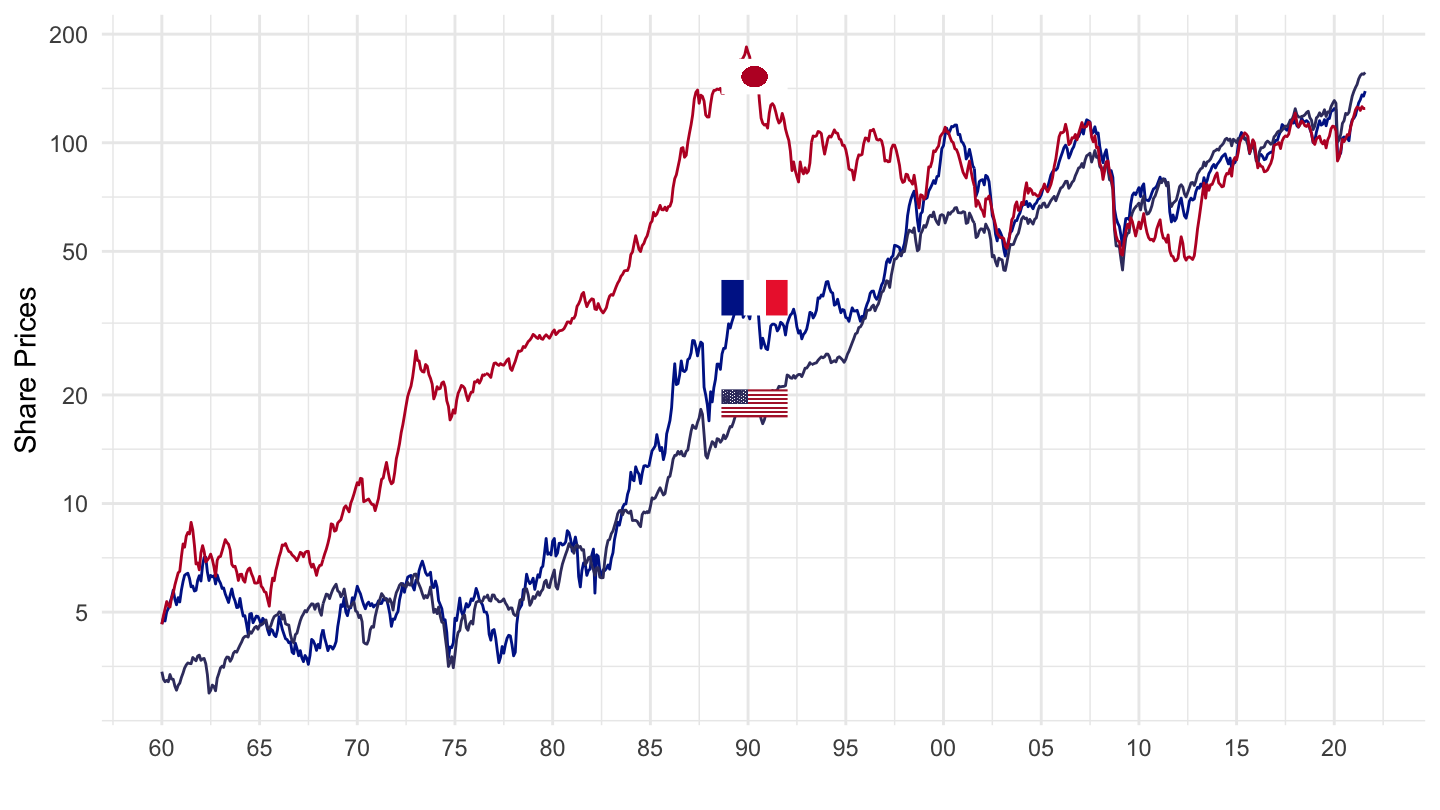

Japan, Switzerland, France

Stock Price “Bubbles” - Data on Market Capitalization

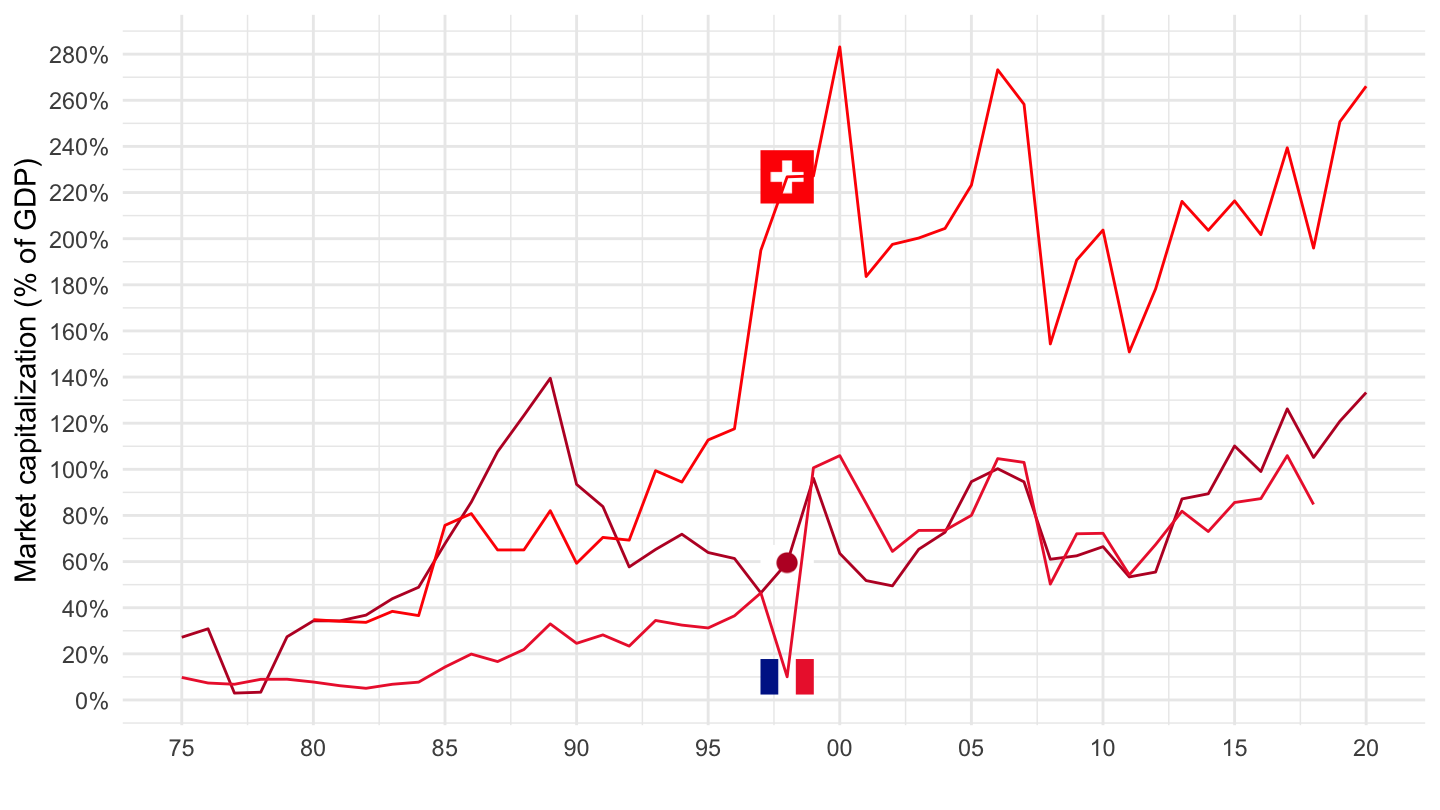

Japan, Switzerland, France

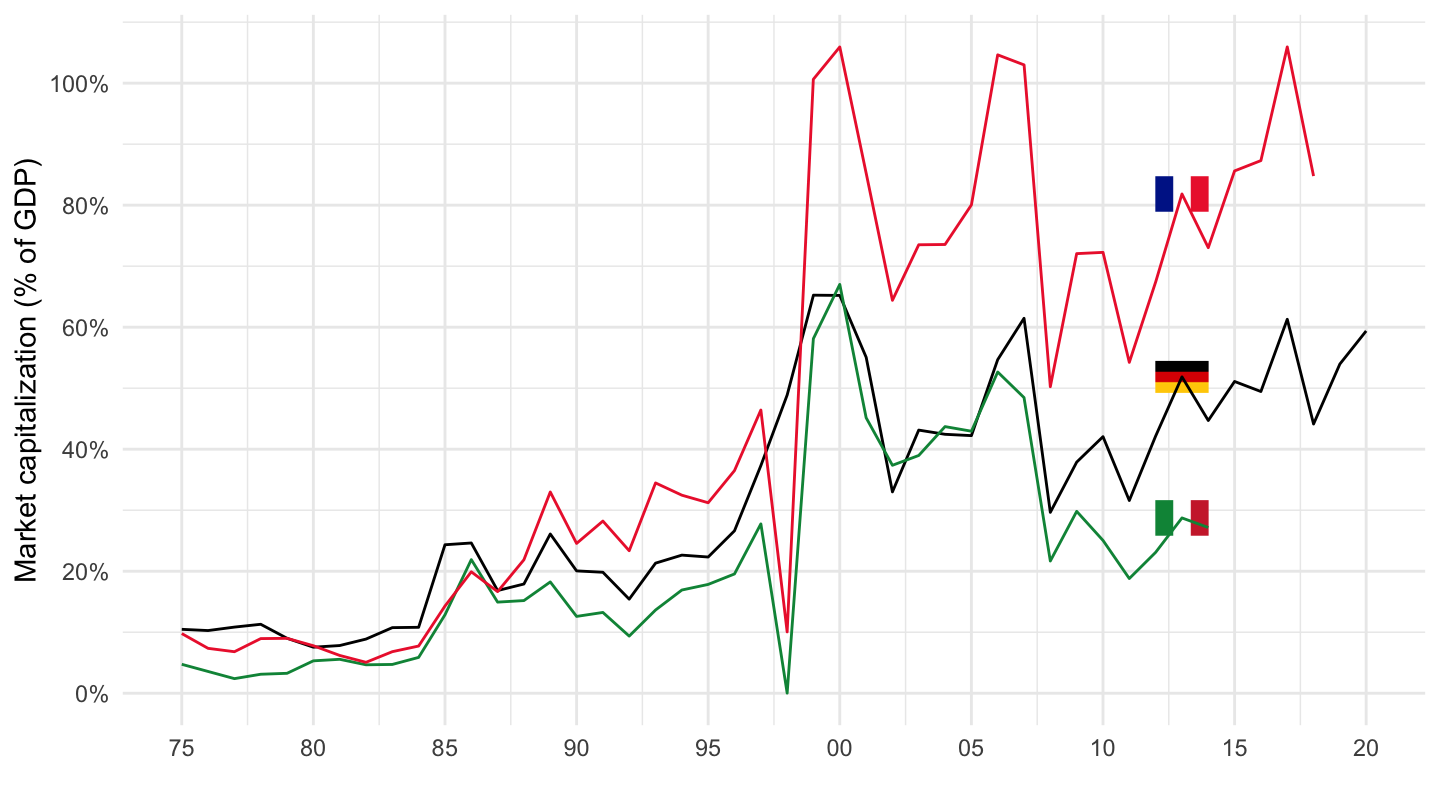

France, Germany, Italy

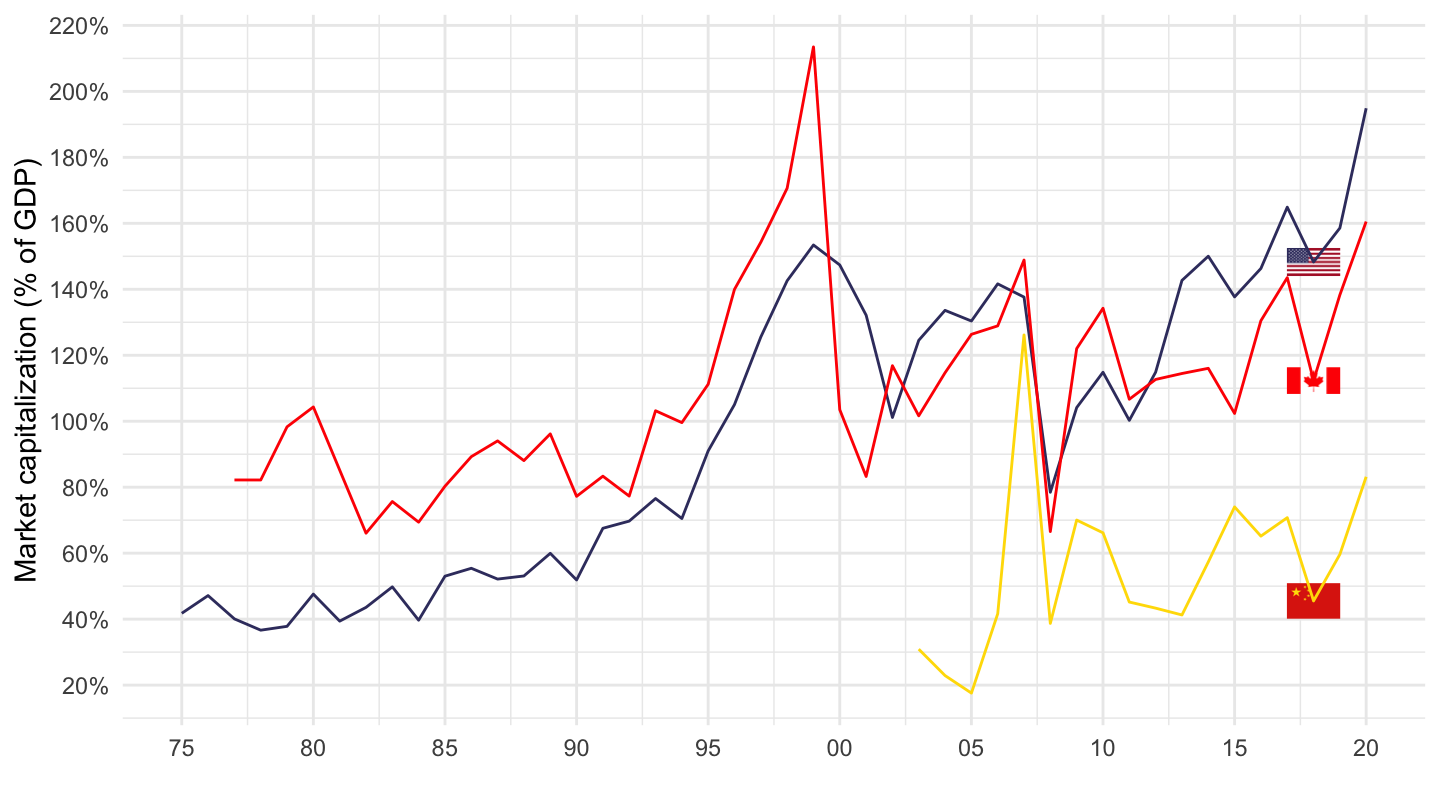

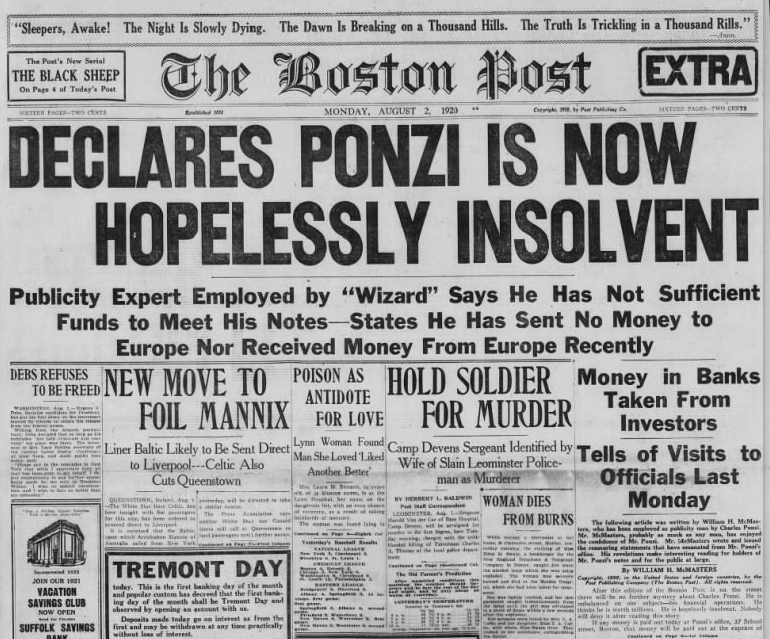

China, United States, Canada

China, United States, Canada

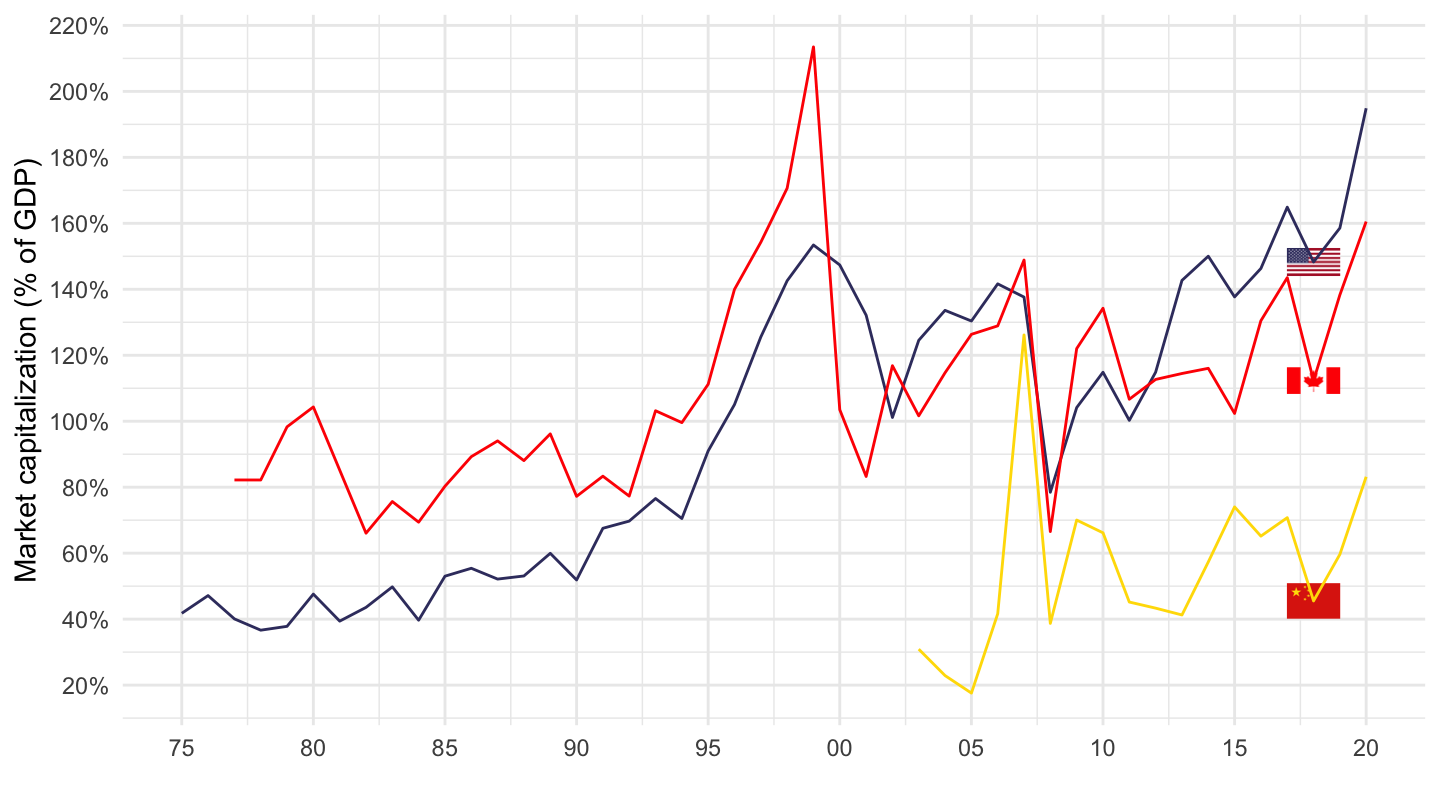

“Bubbles” everywhere

Bitcoin Mother of all bubbles

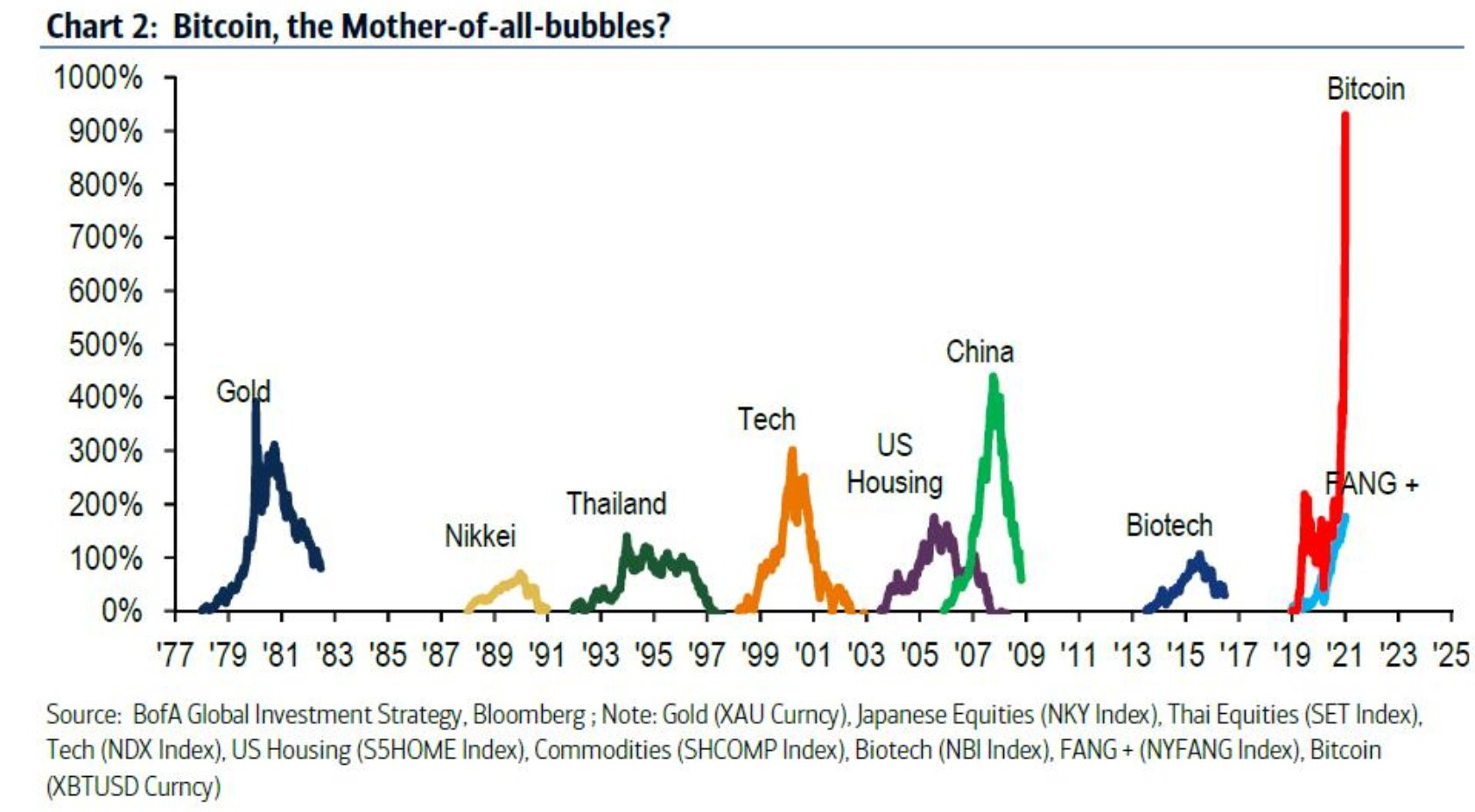

Declares Ponzi is now Hopelessly Insolvent

Ponzi investors try to retrieve money

Keynes again, Chapter 12

Declares Ponzi is now Hopelessly Insolvent

Economist cover

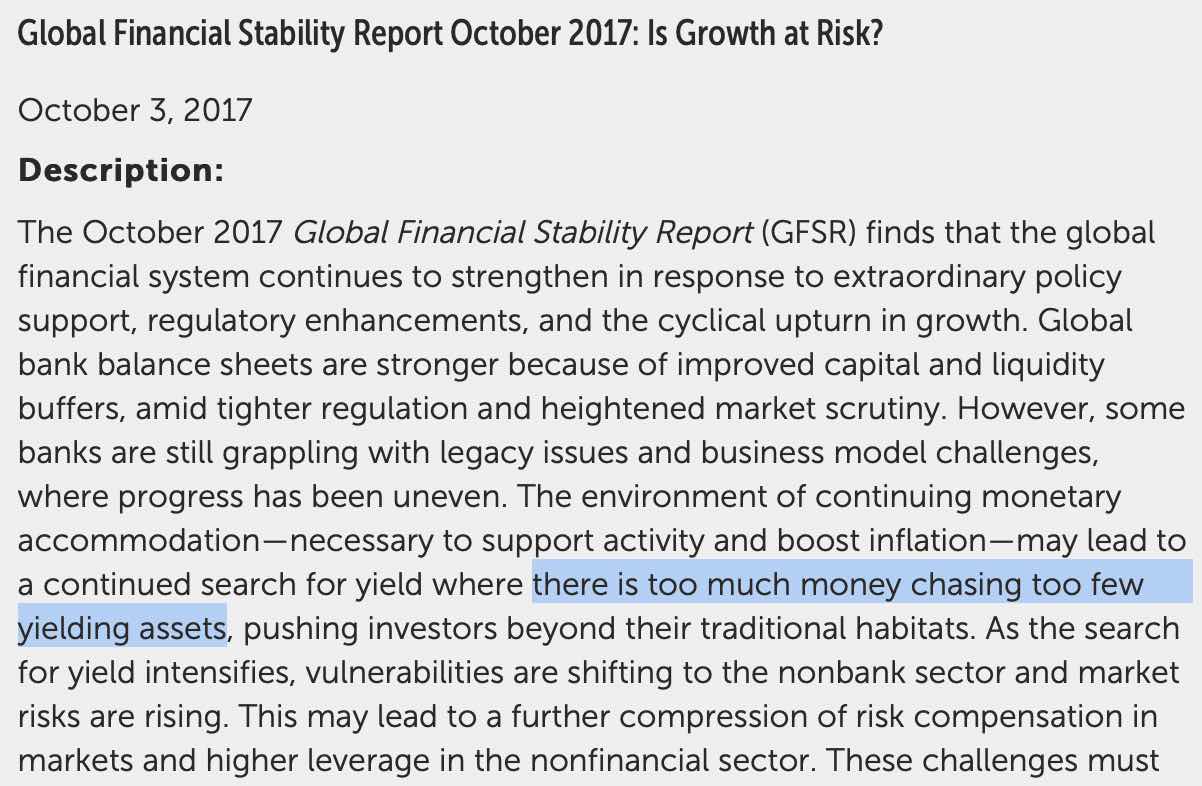

Too much cash is chasing too few desirable assets

People fear they’ve got too much cash

Too much money chasing too few assets

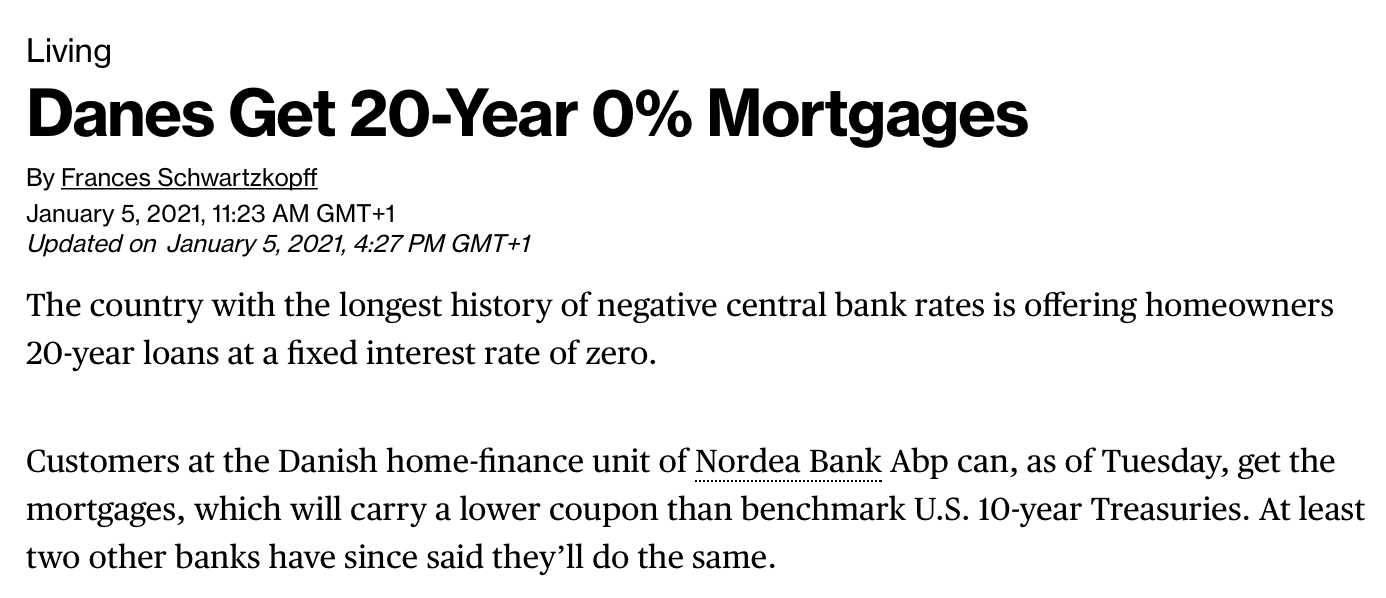

Danes get 20-year 0% Mortgages

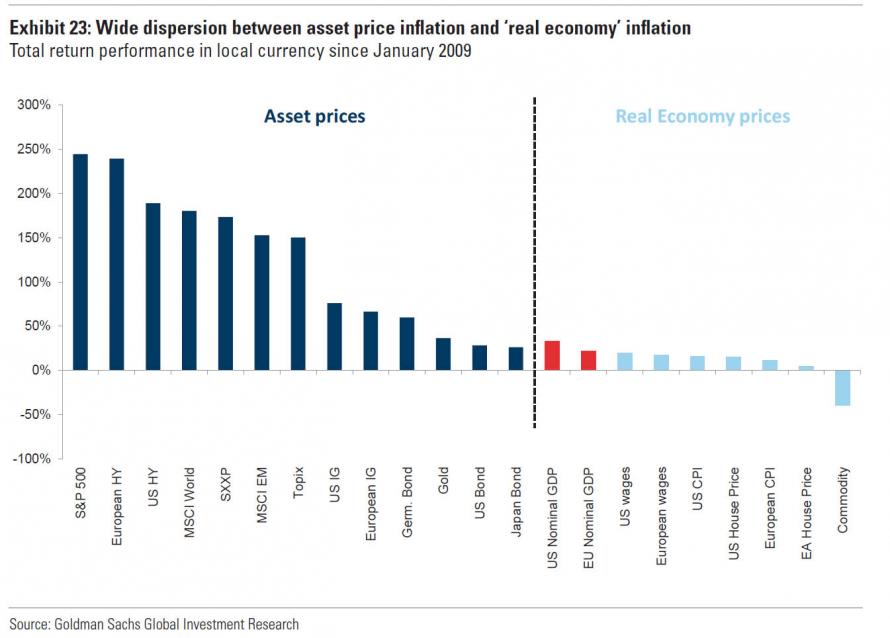

Inflation of different asset prices

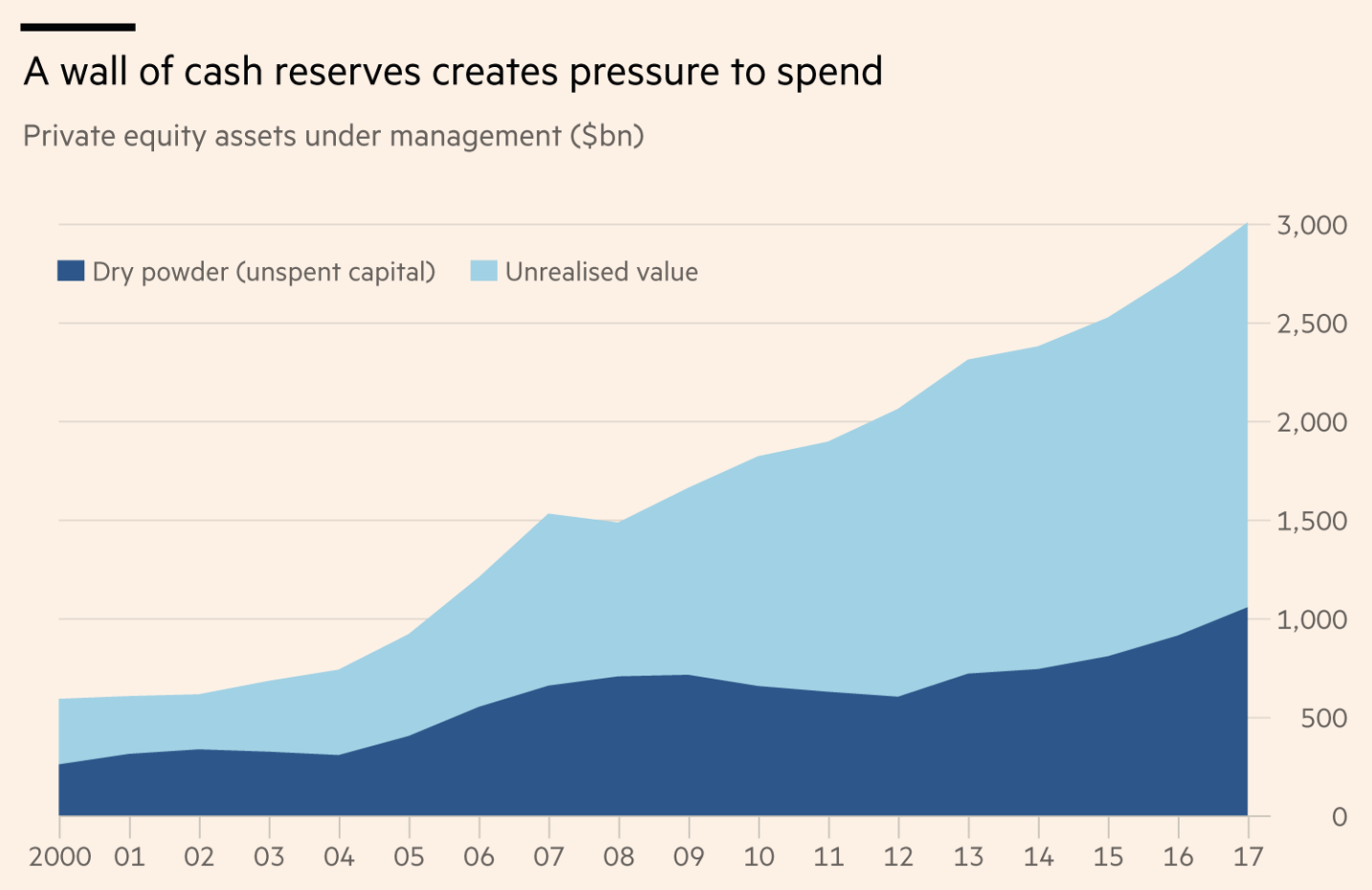

Private equity: flood of cash and buyout bubble fears

Private equity: wall of cash reserves

Also in China

“Bubbles” in Sovereign Debt

Investment Bubble ?

IMF Aid Requested

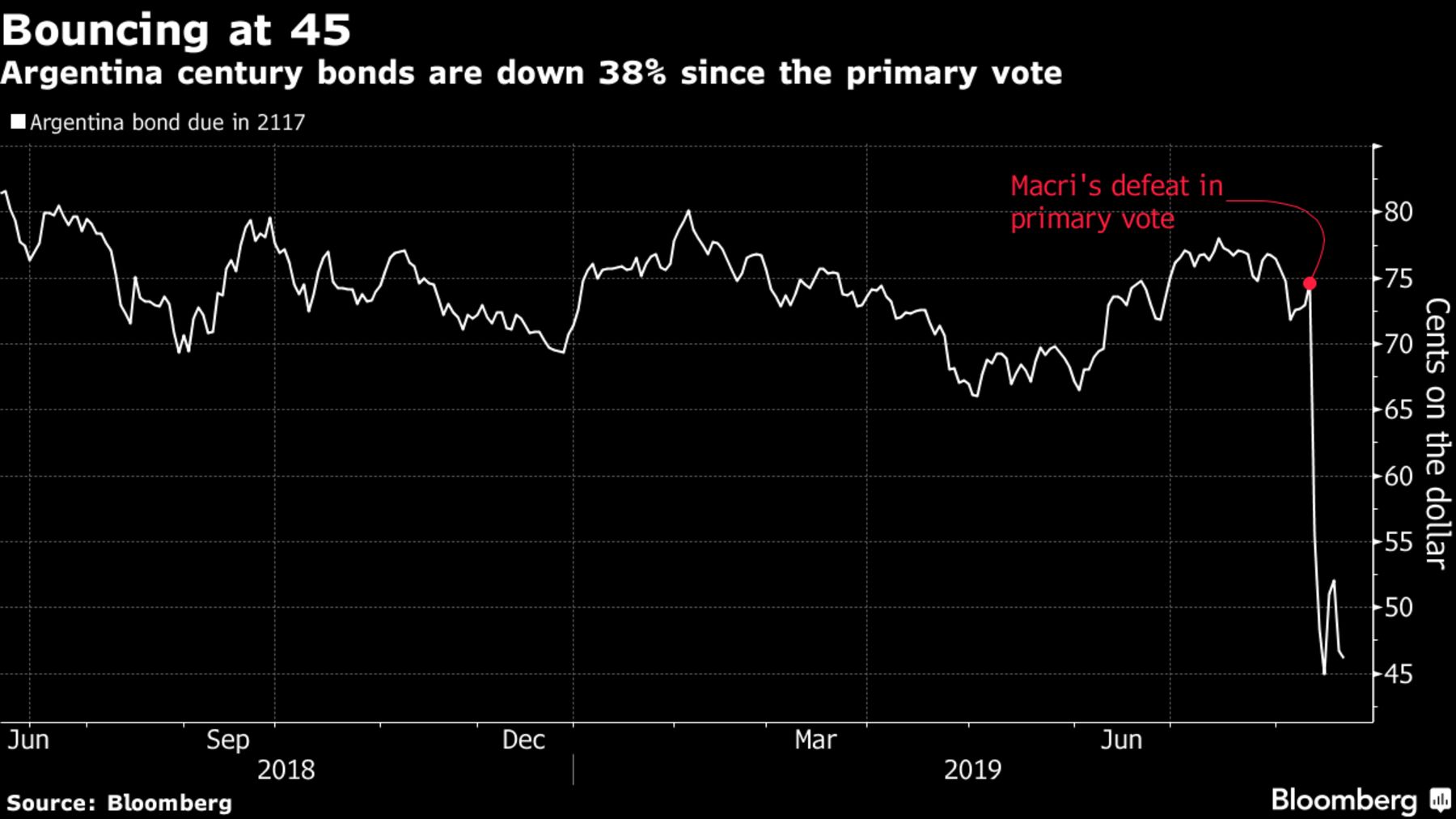

Primary Vote in Argentina

“Rational bubble” in Public Debt ?

Again, as I told you, I do not believe that public debt is a big issue. You can really think of public debt as a bubble.

Public debt is a stable alternative to private bubbles, either credit or housing / equity.

Is the problem in booms or in busts ?

Very much the question between Austrian and Keynesian economics. Watch the video which follows, which you might already know about.

Also watch the debate with Furman, Summers, Bernanke, Rogoff and Blanchard, who almost reach an agreement that public debt is probably not that bad.

Economist cover