November 18, 2020

Introduction

Links

There are several versions of these slides:

If you want to know more, there also exists a more advanced version of these slides (Ph.D. Level), as well as some related research of mine - this is absolutely not exam material:

Related Research. Dynamic inefficiency. Secular stagnation.

Plan

Data on government debt

Worries about government debt

Public Debt and Wars

r and g, Sustainability of Public Debt

2007-2009, 2010-2013 and public debt

Arguments for government debt

Data on Government Debt

Debt to GDP: % or years ?

Standard practice is to express debt to GDP ratios as %.

Mathematically speaking, this does not make much sense: Debt is a Stock (measured in dollars), GDP is a Flow (measured as dollars per year, or dollars per quarter). Dividing a stock by a flow gives you a notion of time (duration), not a %.

So when people say: U.S. public debt is over 100% of GDP, in fact they should be saying: U.S. Debt is over 1 year of production.

Years should then be compared to years: for exemple, the maturity of the debt, etc.

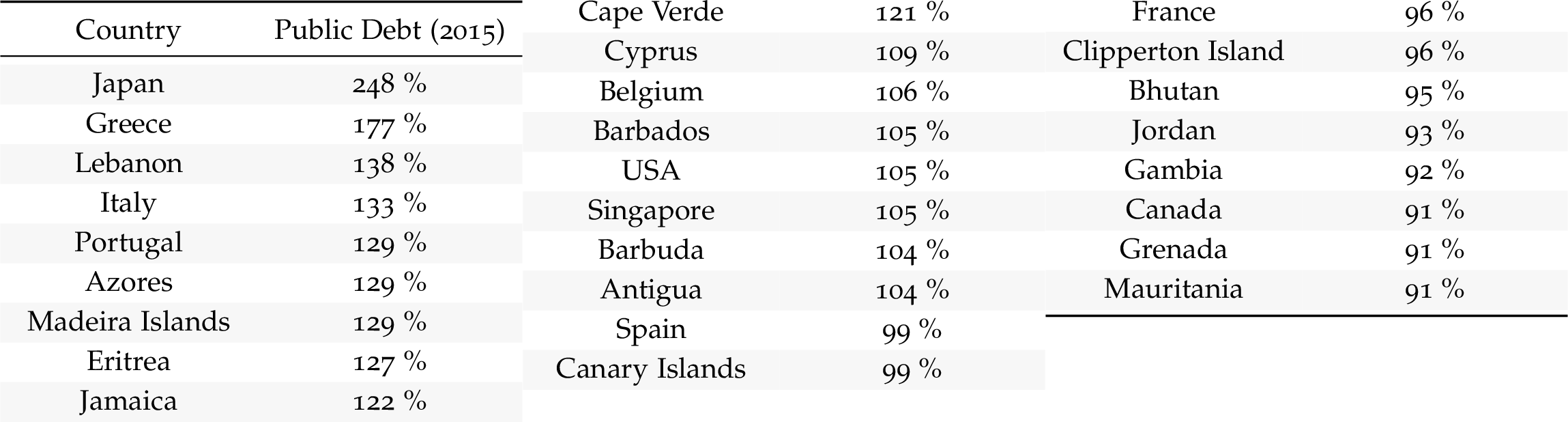

High Debt to GDP Ratios

Low Debt to GDP Ratios

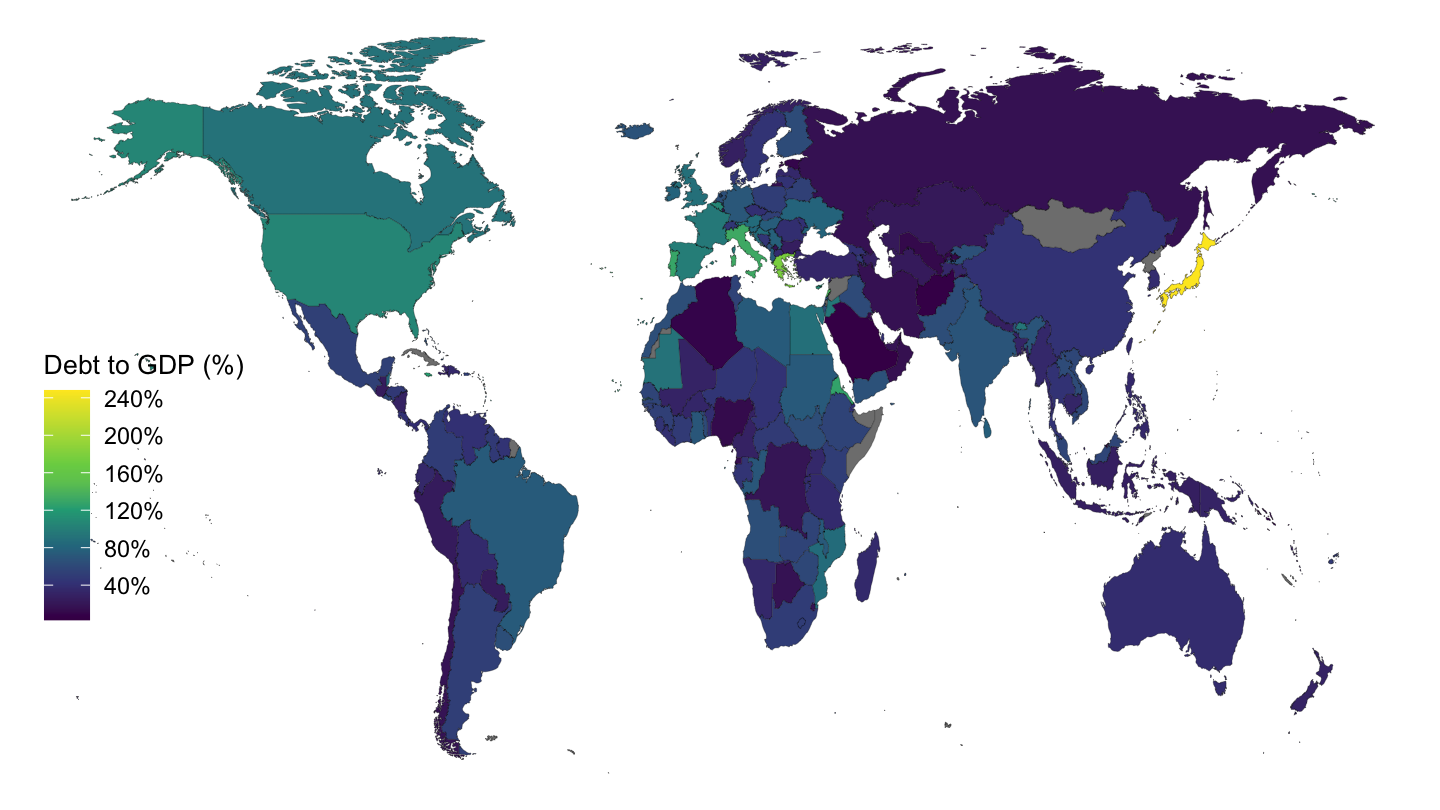

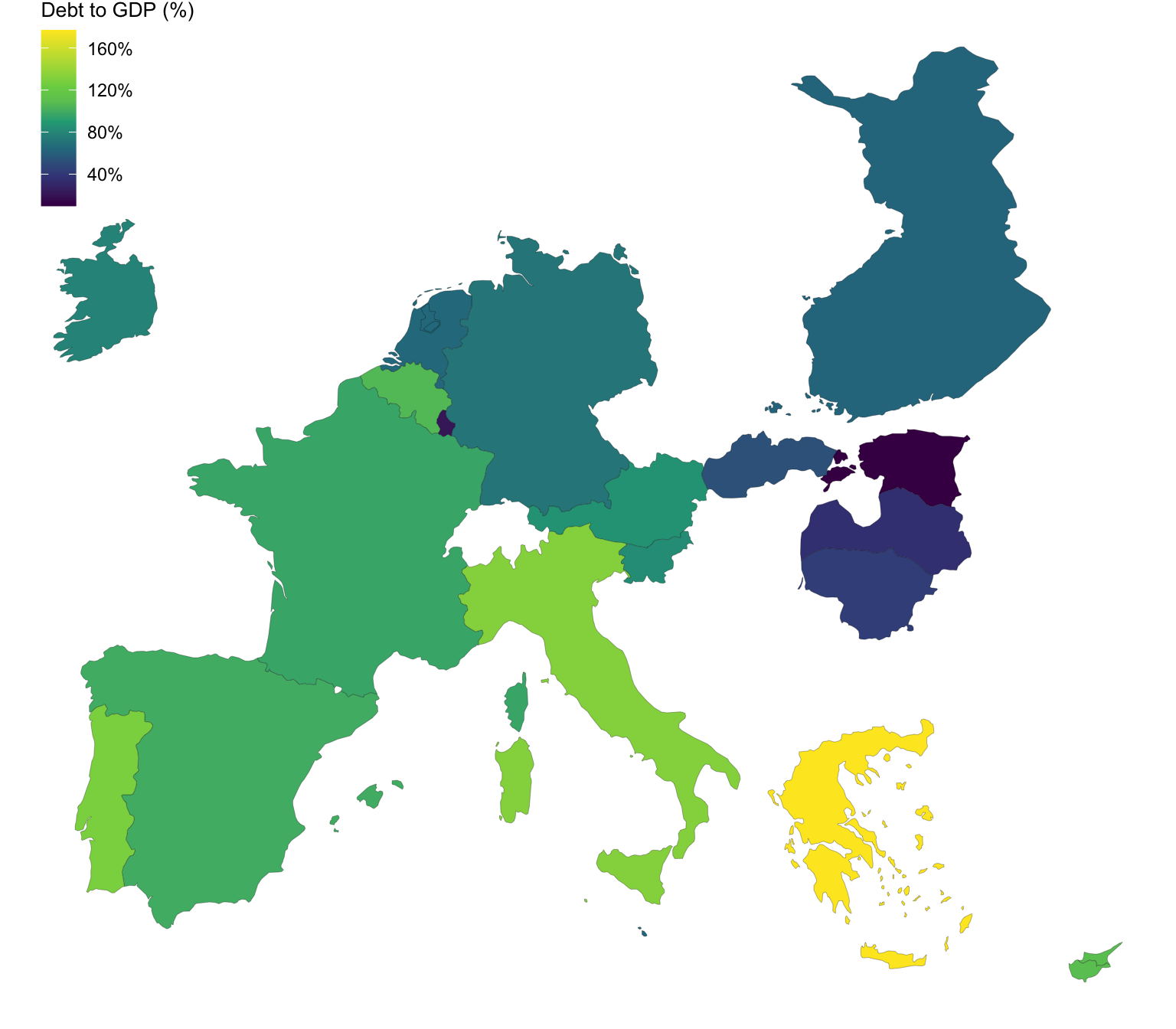

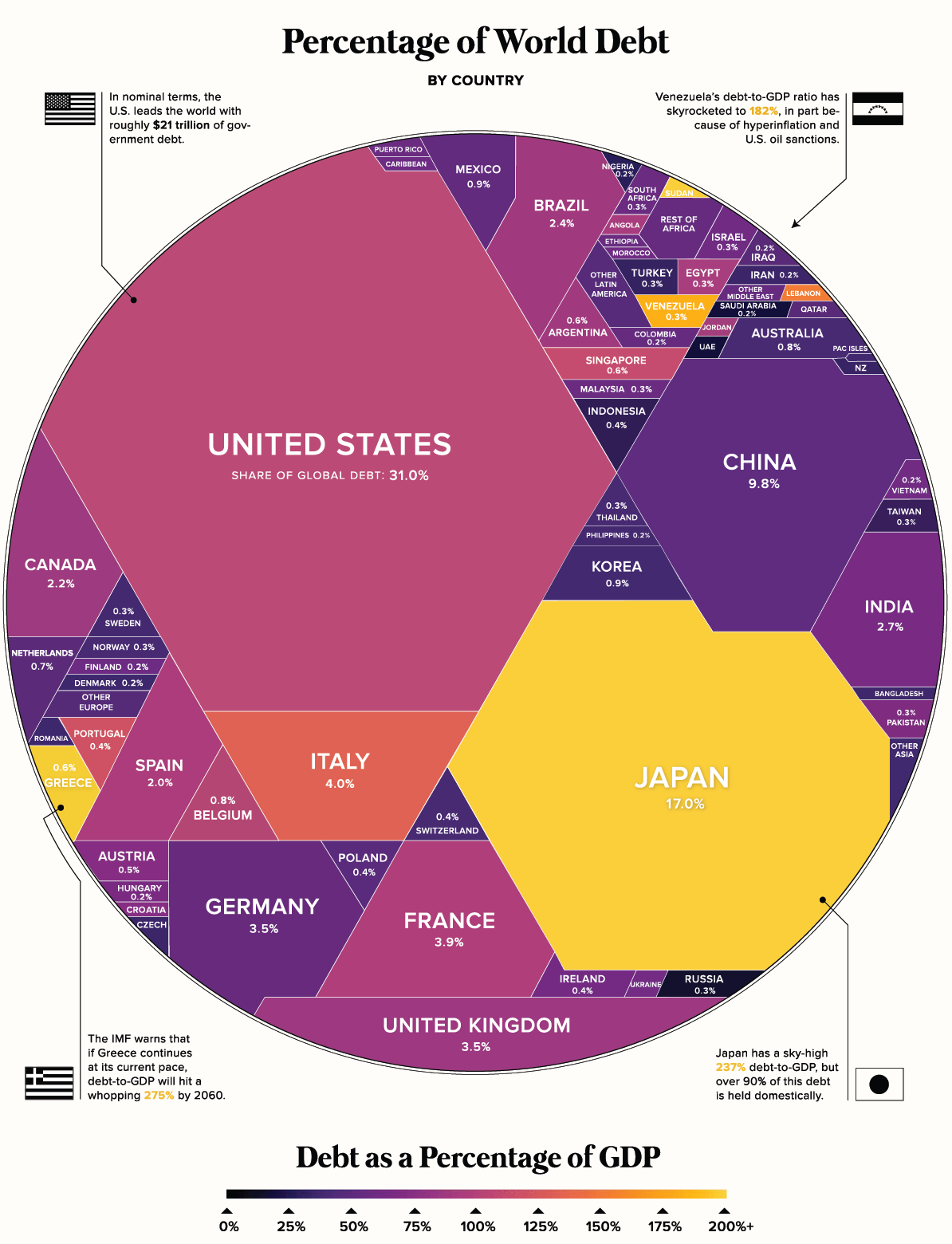

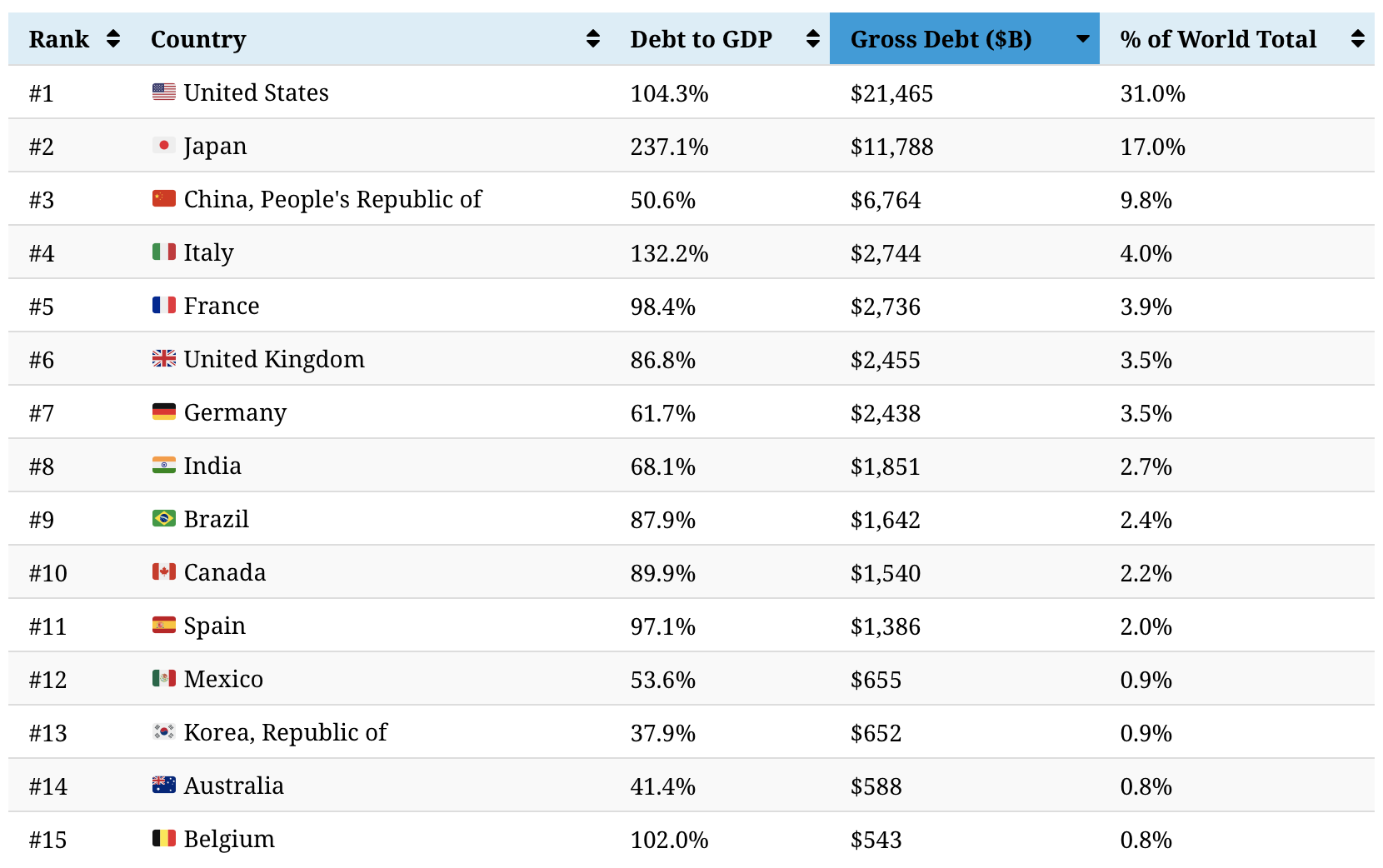

Debt/GDP around the World

Zooming in on Europe

Eurozone

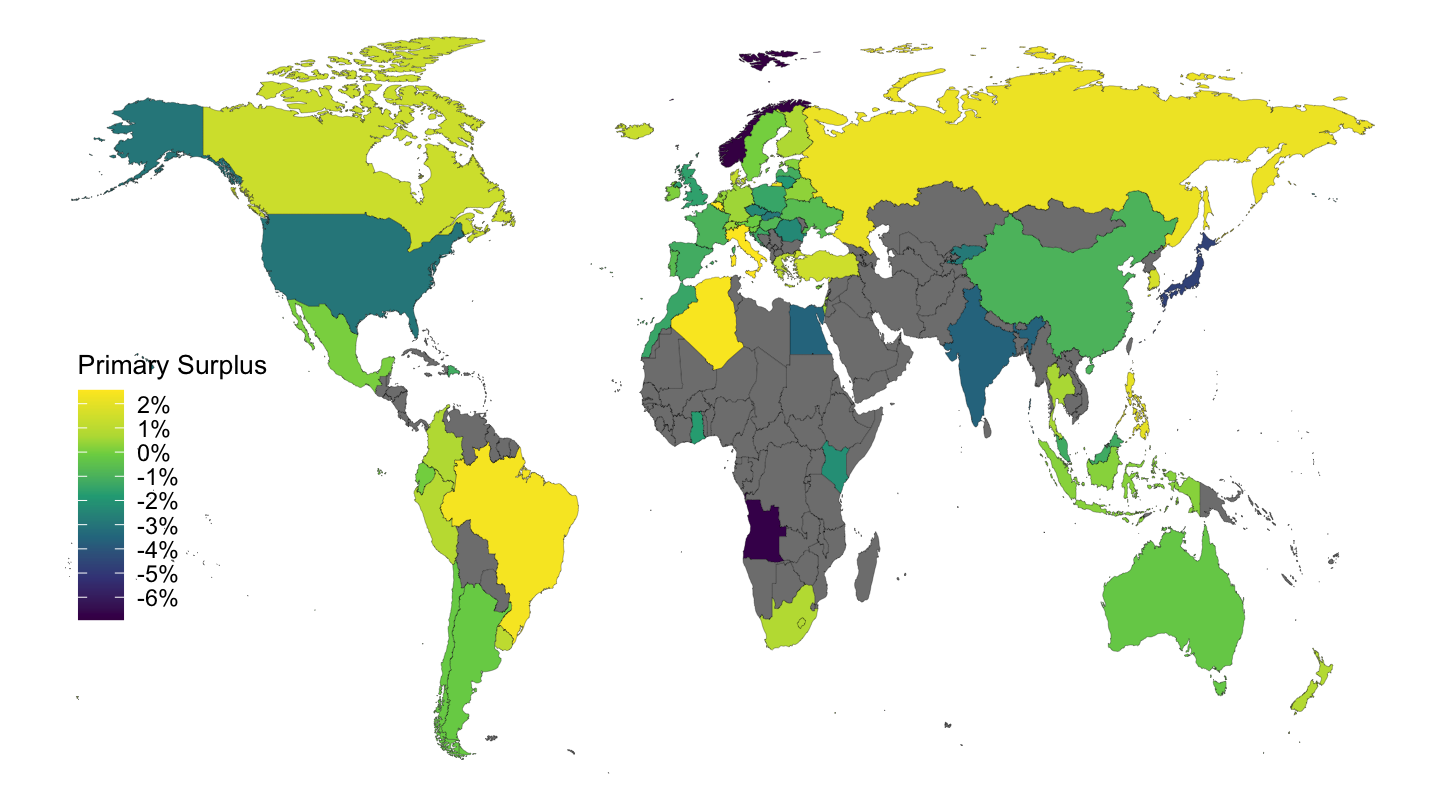

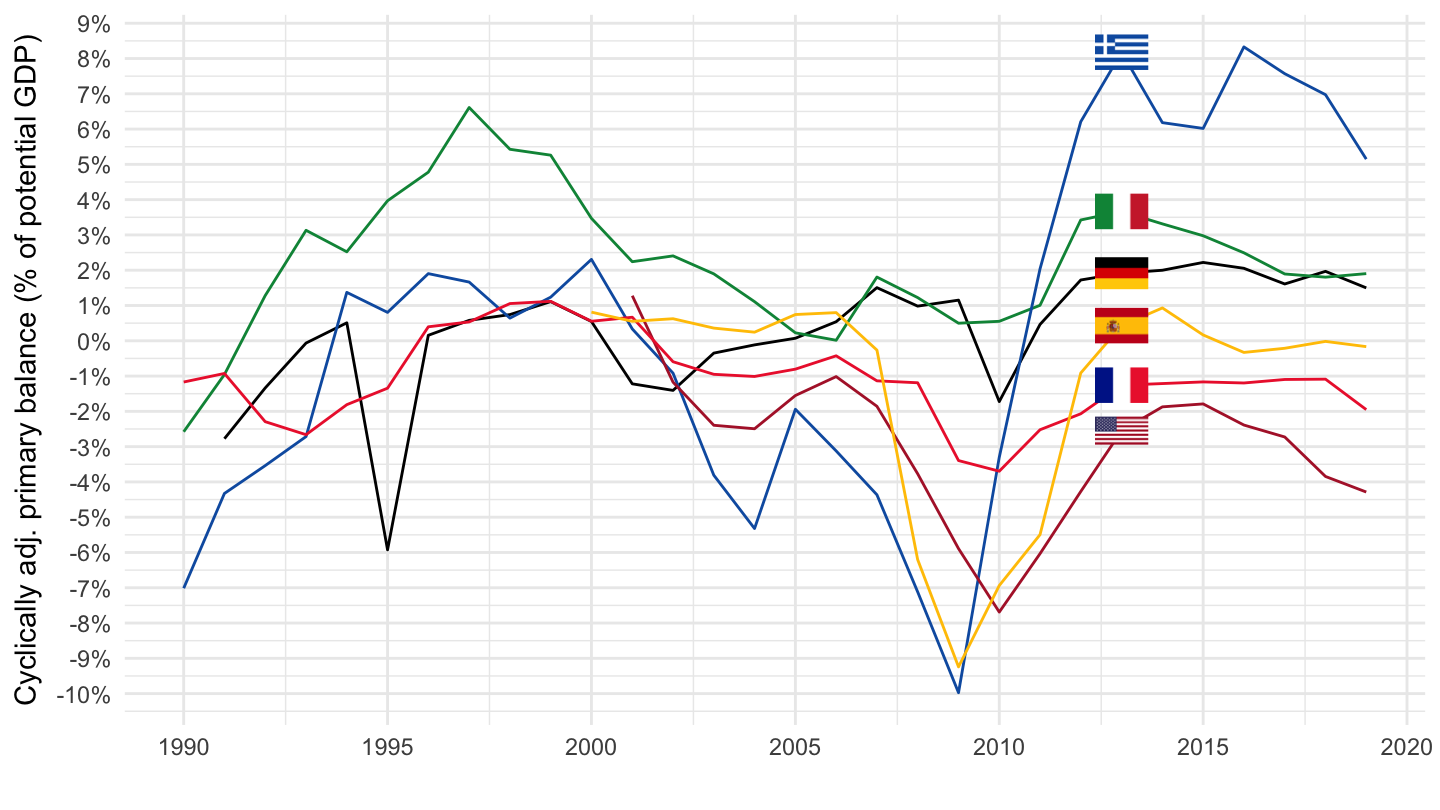

Cycl. Adj. Primary Surplus (% of Pot. GDP)

Cycl. Adj. Primary Deficit (% of Pot. GDP)

Primary Deficits around the World

Cyclically-Adjusted Primary Deficits

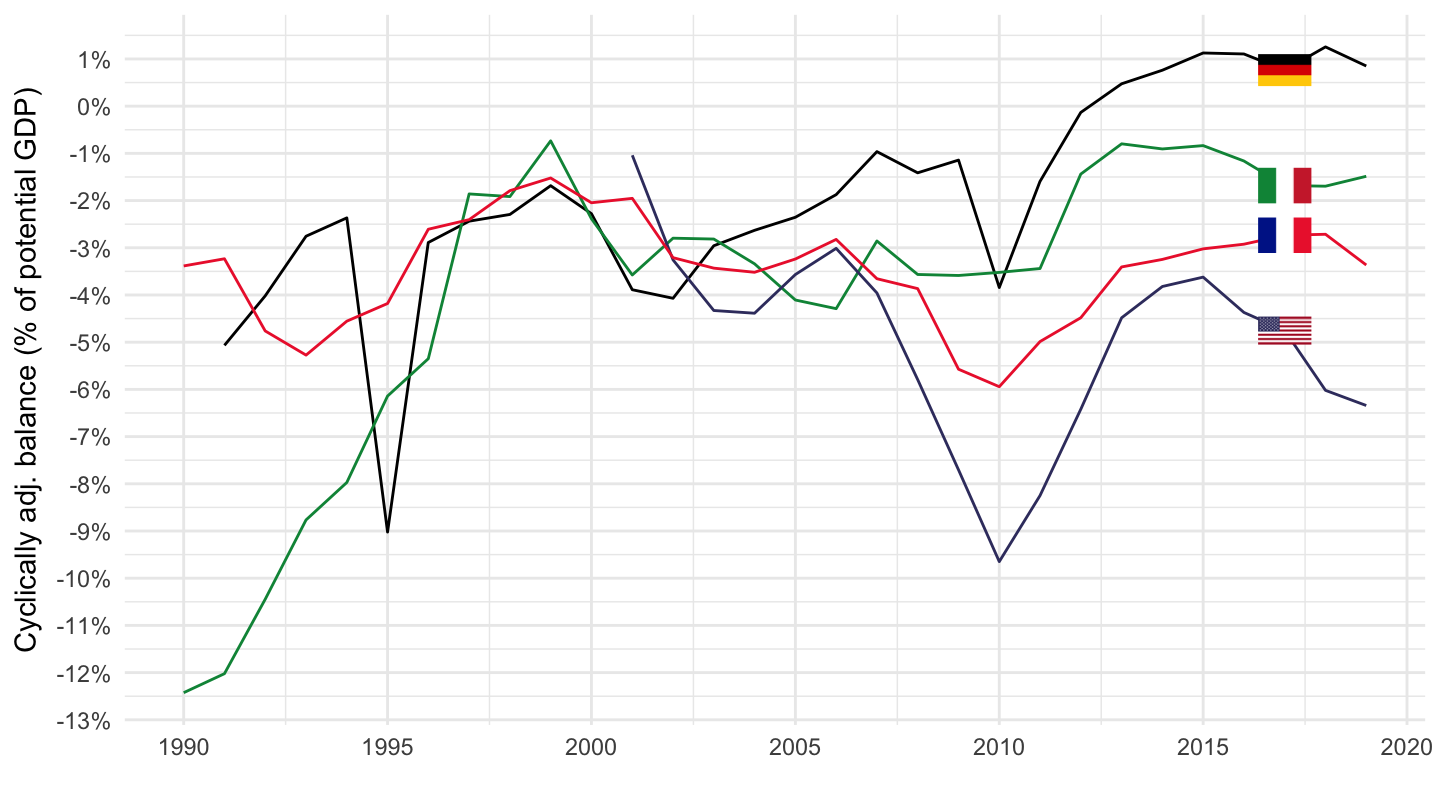

Total Balance

United States (Source: IMF)

United Kingdom (Source: IMF)

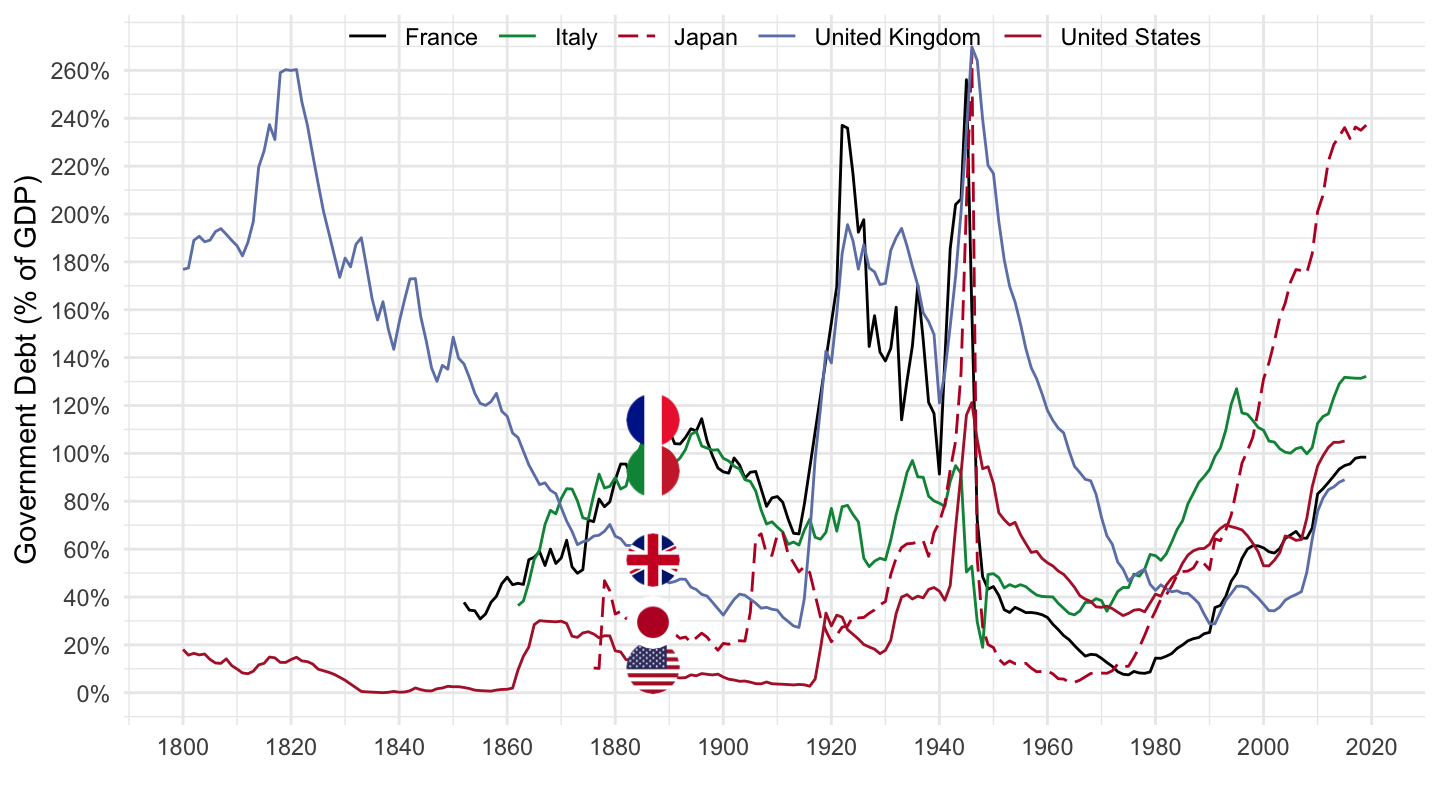

U.S., U.K.

U.S., U.K., France

## U.S., U.K., France, Italy, Japan

## U.S., U.K., France, Italy, Japan

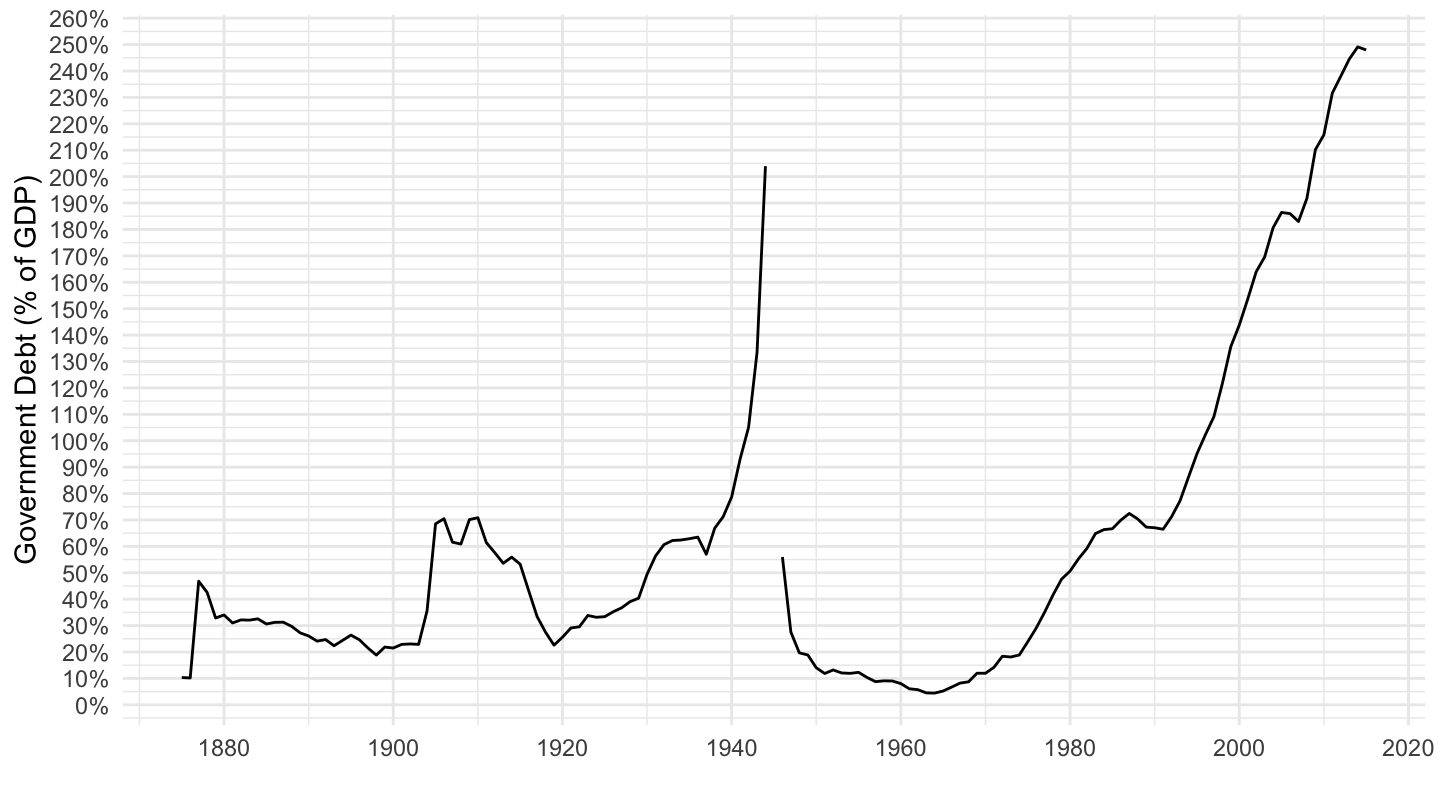

Japan (Source: IMF)

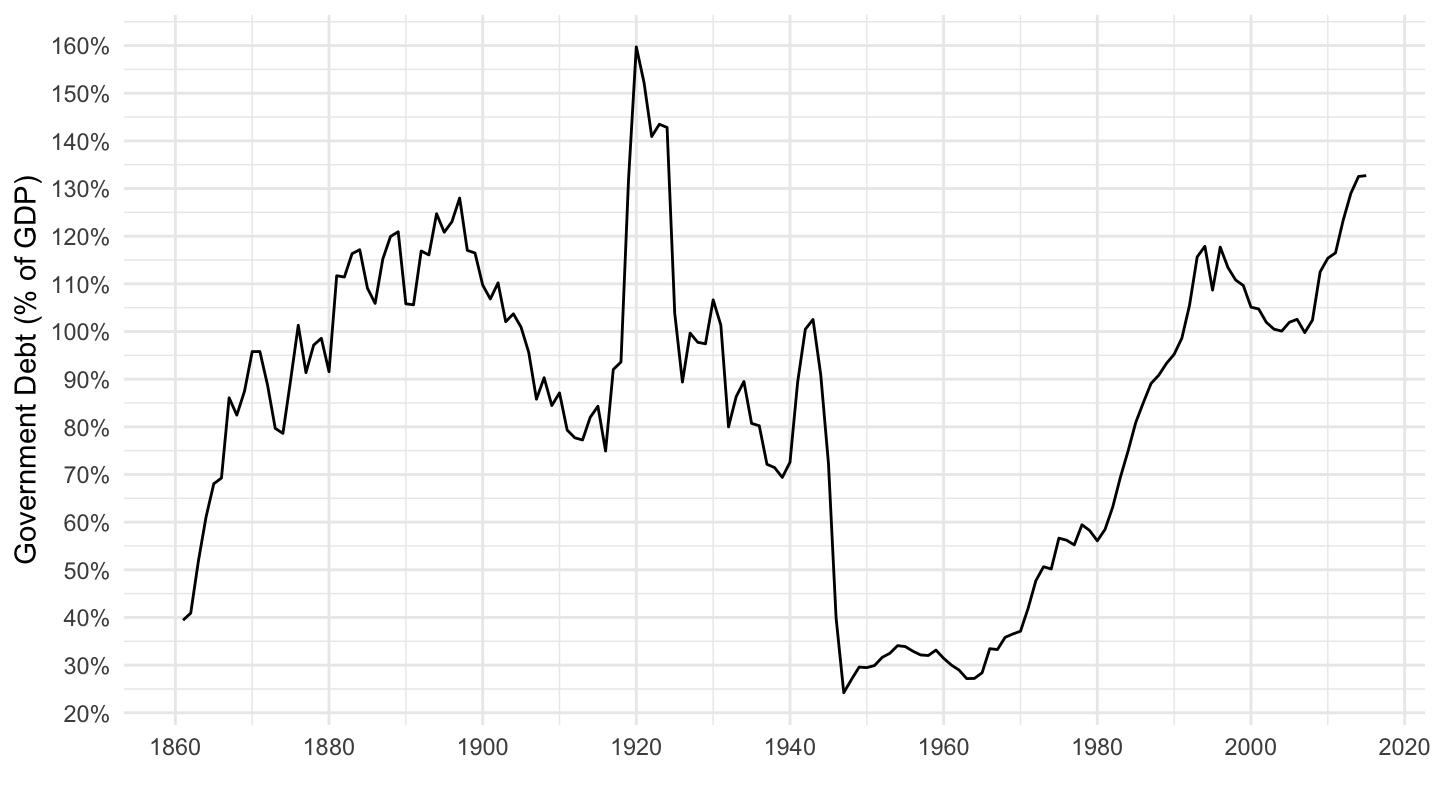

Italy (Source: IMF)

France (Source: IMF)

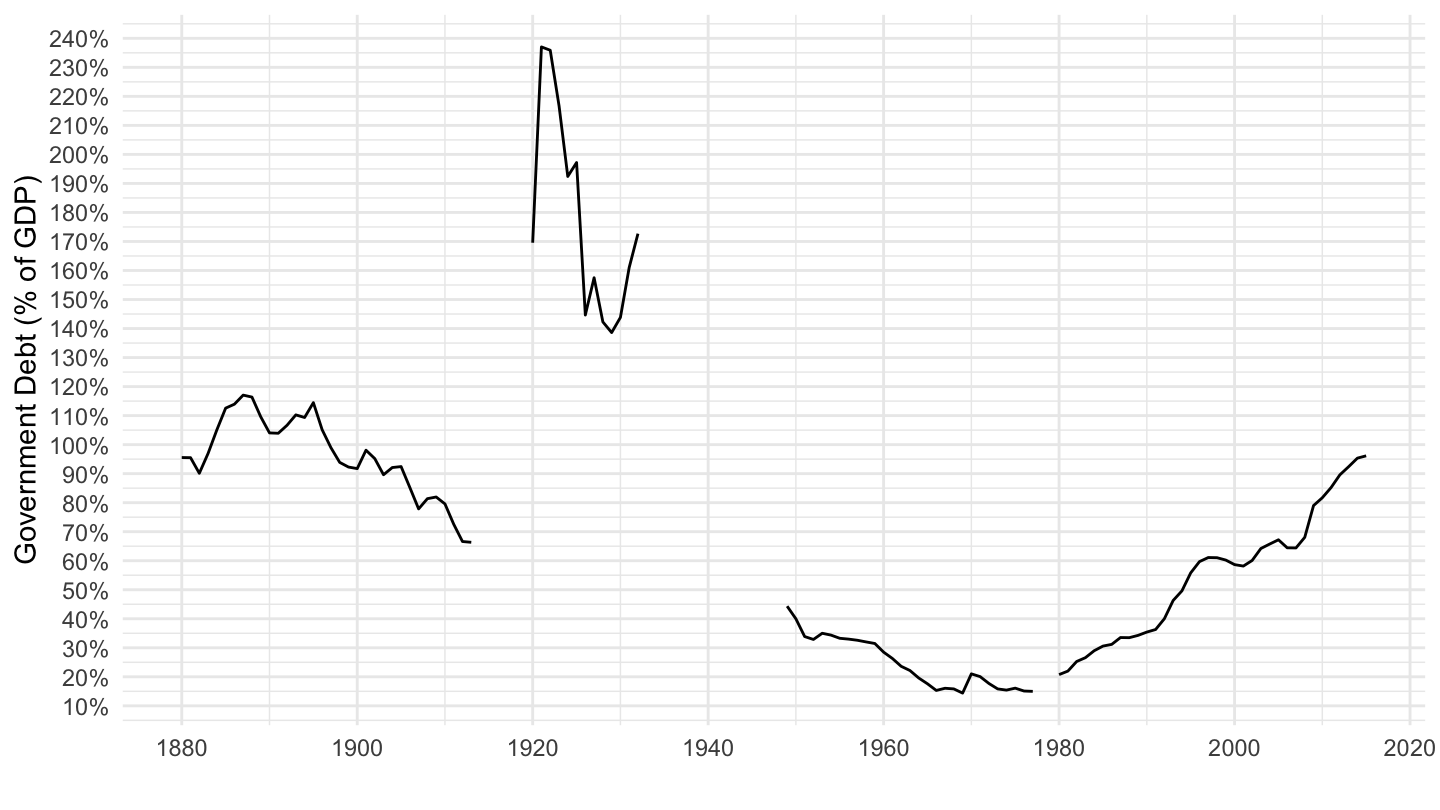

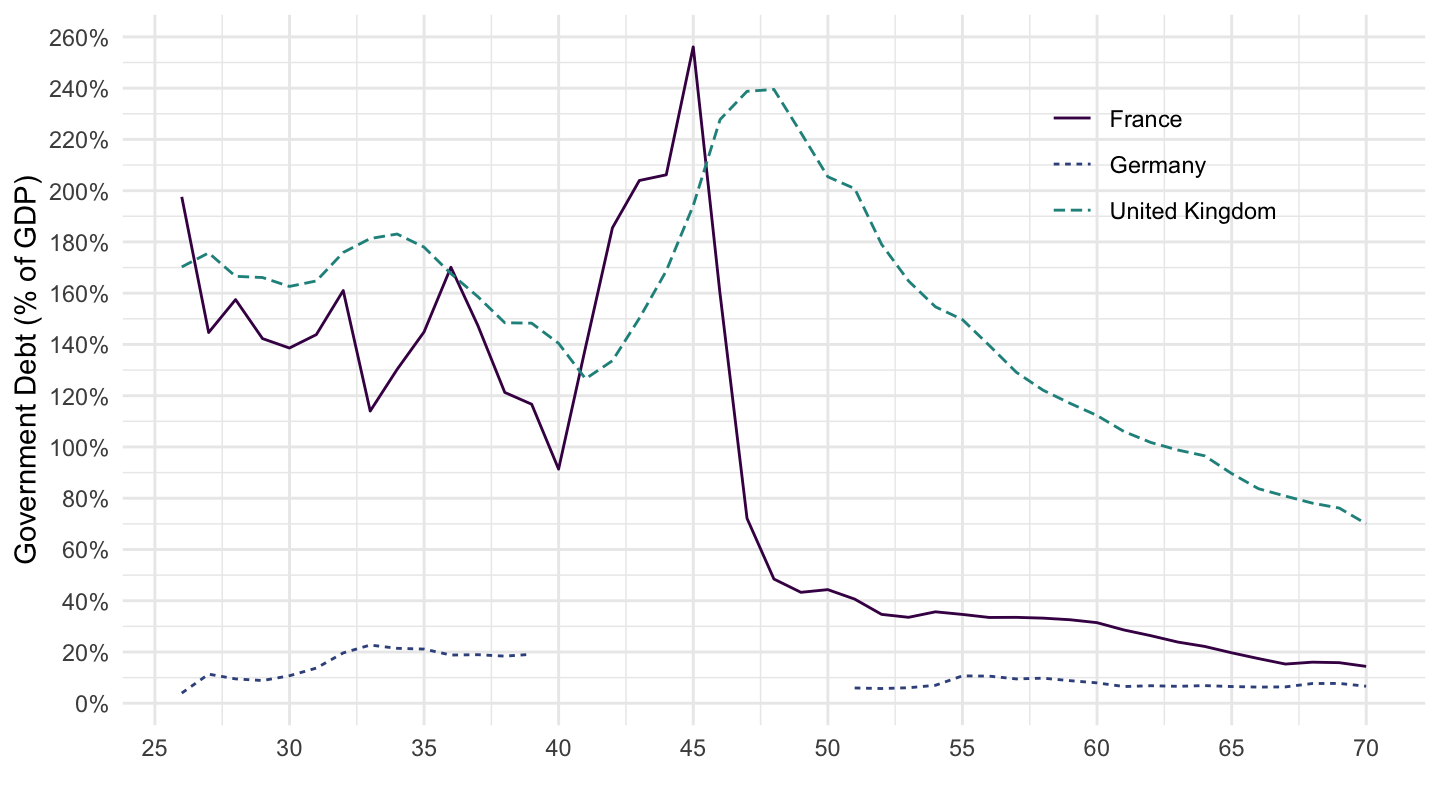

Germany, France, UK (Source: GFD)

World Government Debt

Size of Public Debt

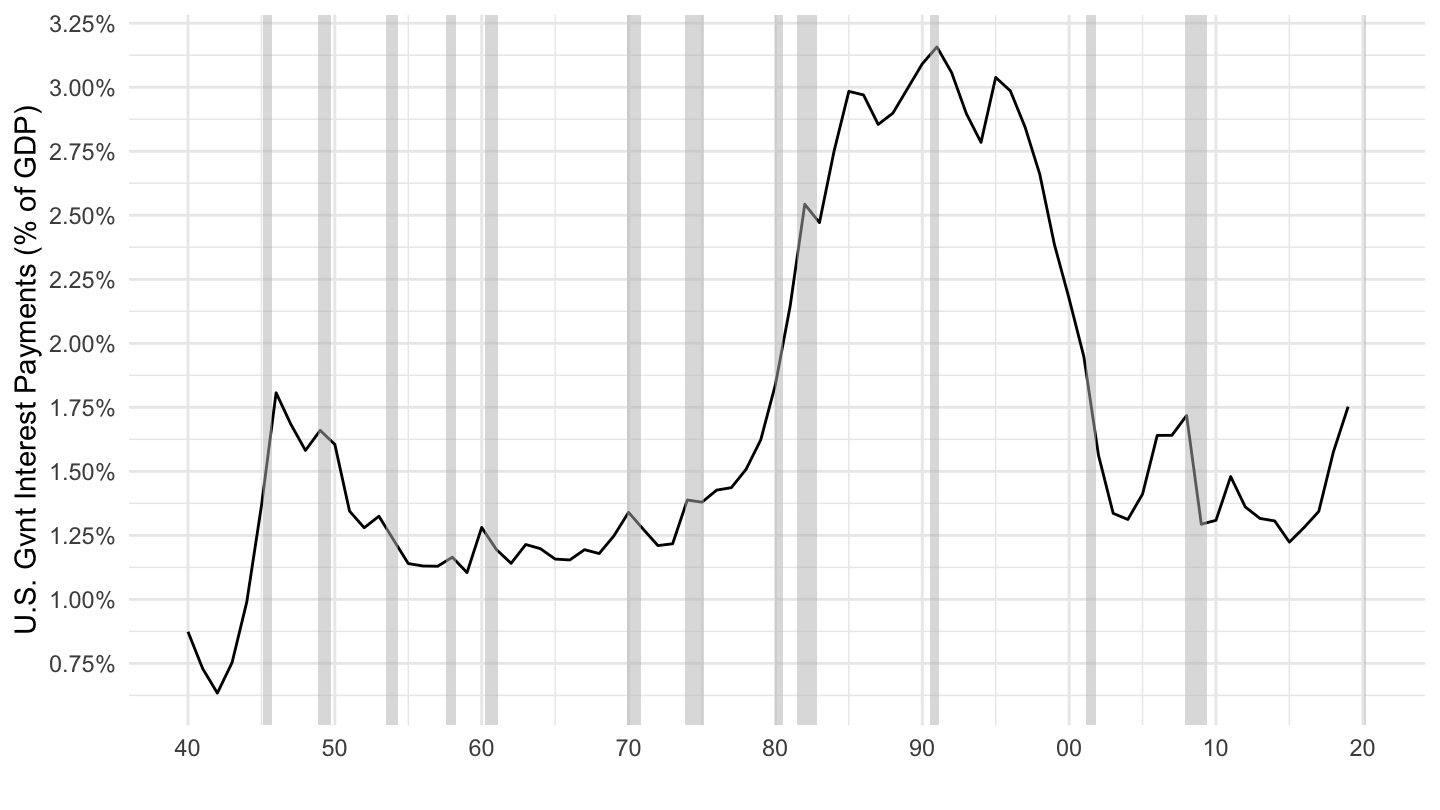

Debt / GDP is not a great measure

GDP is an annual flow.

By contrast, government debt is a stock.

Debt/GDP is a bit misleadingly high because it compares a stock in the numerator, to a flow in the denominator.

It’s much better practice to compute Interest payments / GDP, comparing a flow with a flow.

Or to compute Debt / Wealth, comparing a stock with a stock.

In the following slides, we shall do just that.

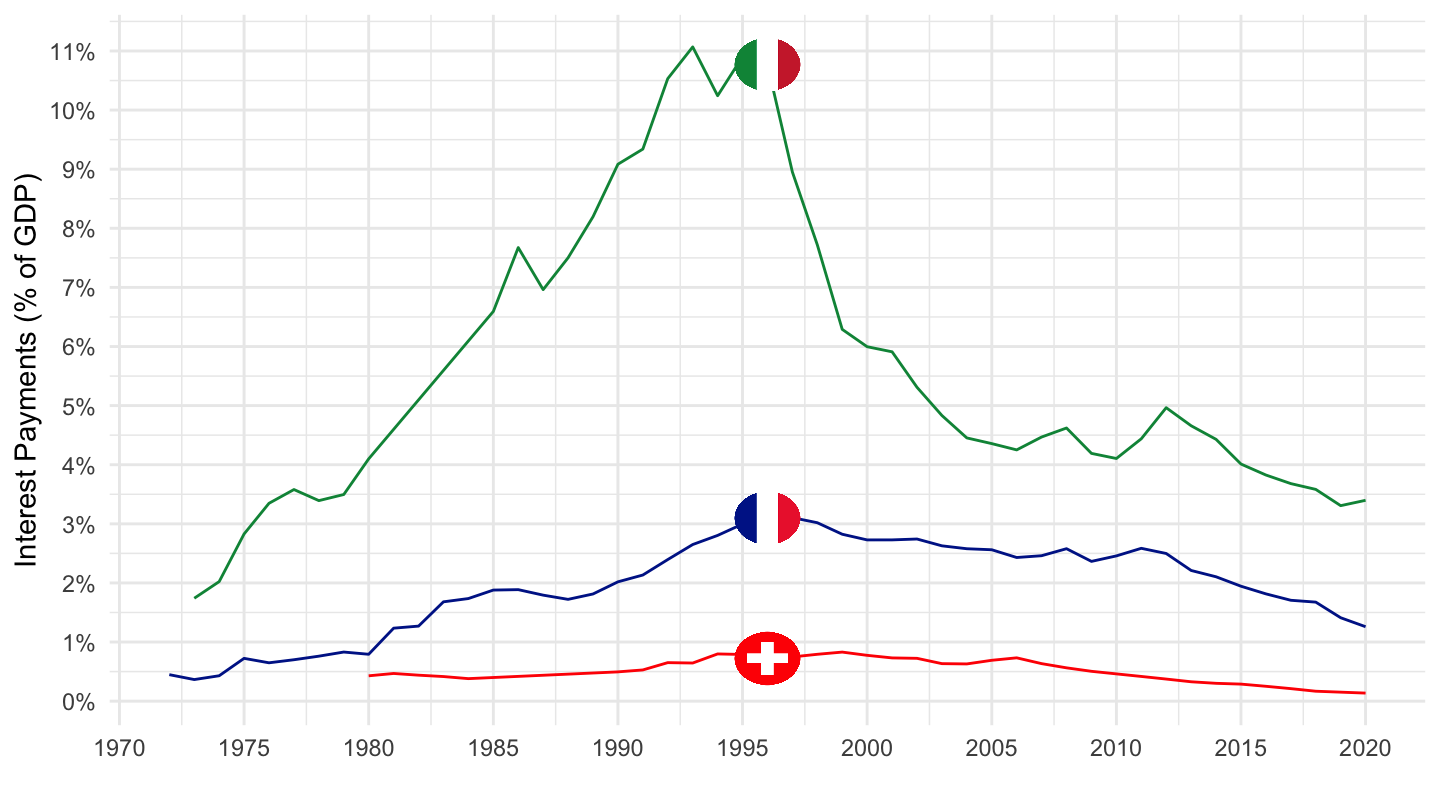

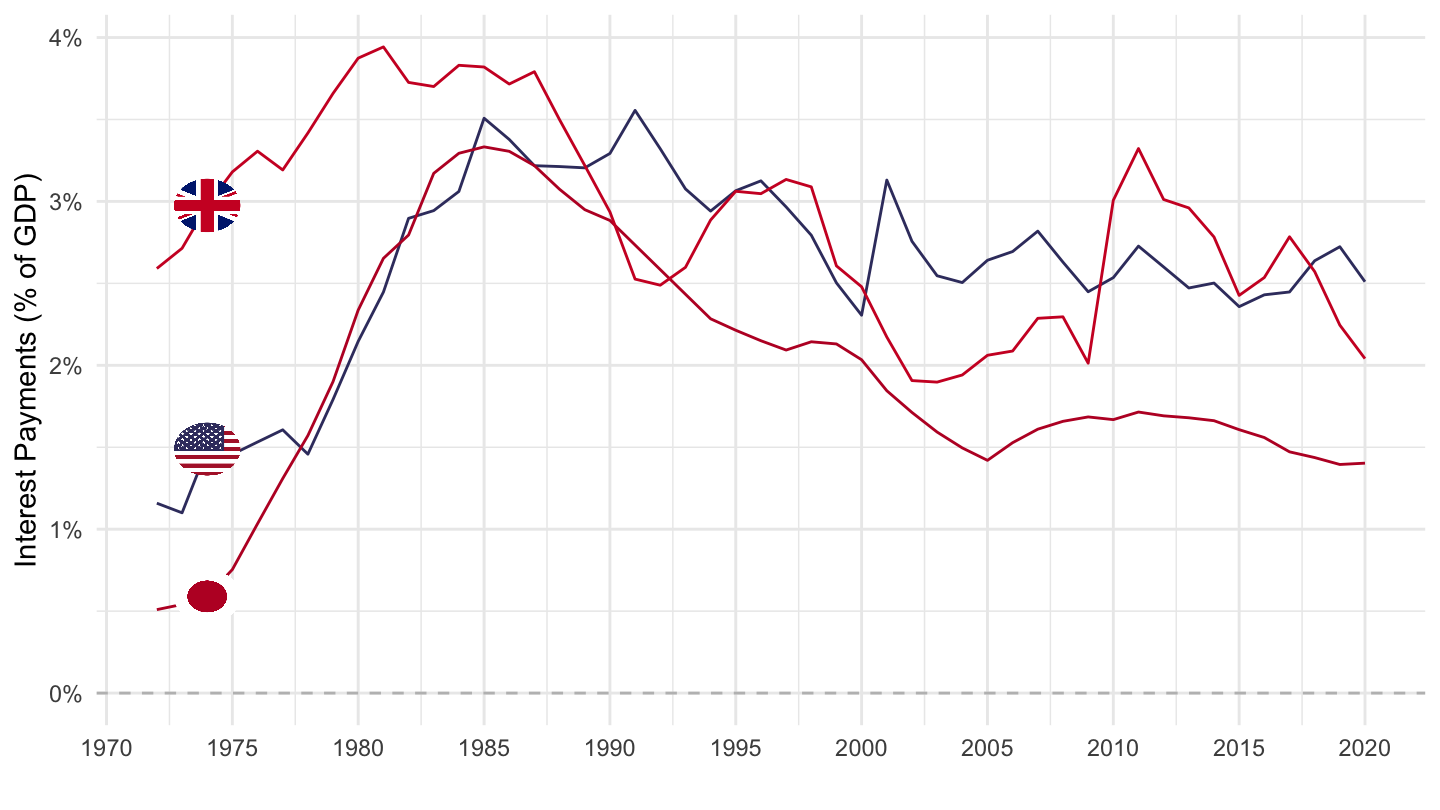

Interest payments / GDP

Interest payments / GDP

Worries about Government Debt

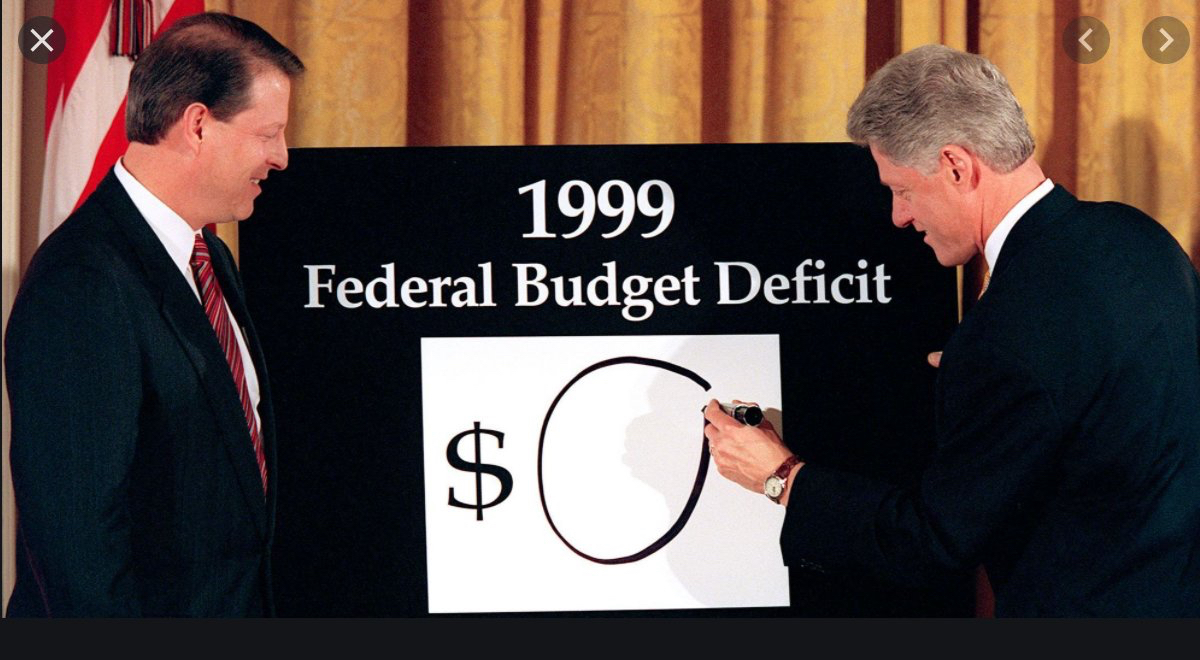

United States

Germany: “Schwarze Null”

Deutschland ist Geldsmeister (Haushalt 2015 ohne neue Schulden)

CDU: Wir stehen zu unserem Fetisch

War es wirklich klug ?

War es wirklich klug ?

German: Frau Pharao, Herr Wesir, sehr beeindruckend, die Schwarze Null. Aber war es wirklich klug, unseren GESAMTEN Etat dafür zu opfern ?

Miss Pharaon, Mr. Wisir, the “black zero.” But was it really wise to sacrifice our ENTIRE budget for it ?

Germans complaining about low interest rates

U.S. National Debt Clock

Popularity of “national debt clocks” shows that at least some people are worried about national debt.

More data: https://www.usdebtclock.org.

Iphone app (!). Link

United States - National Debt Clock

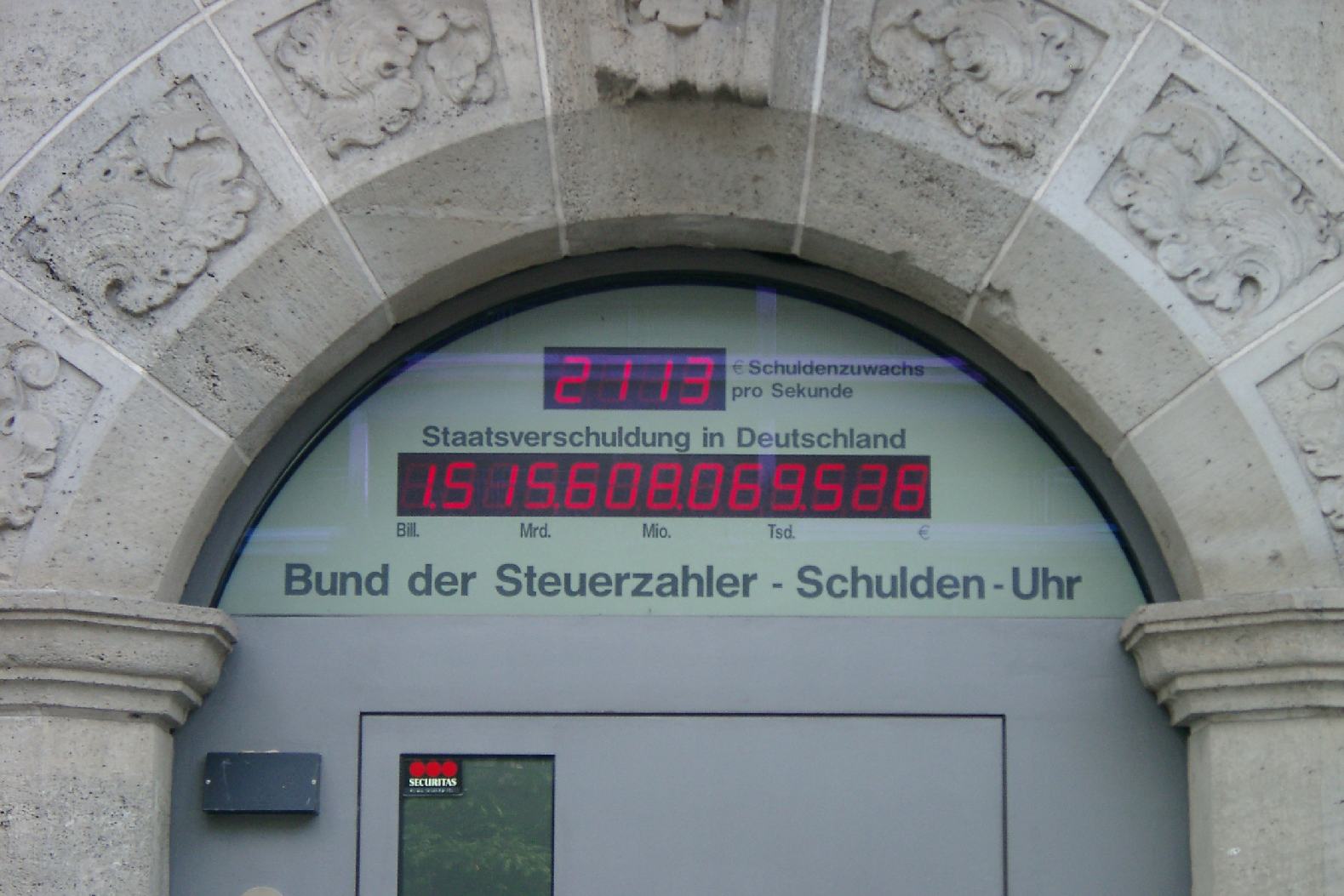

Germany Debt Clock

German tax lobby’s debt clock

German tax lobby’s debt clock

Public debt and dictatorships

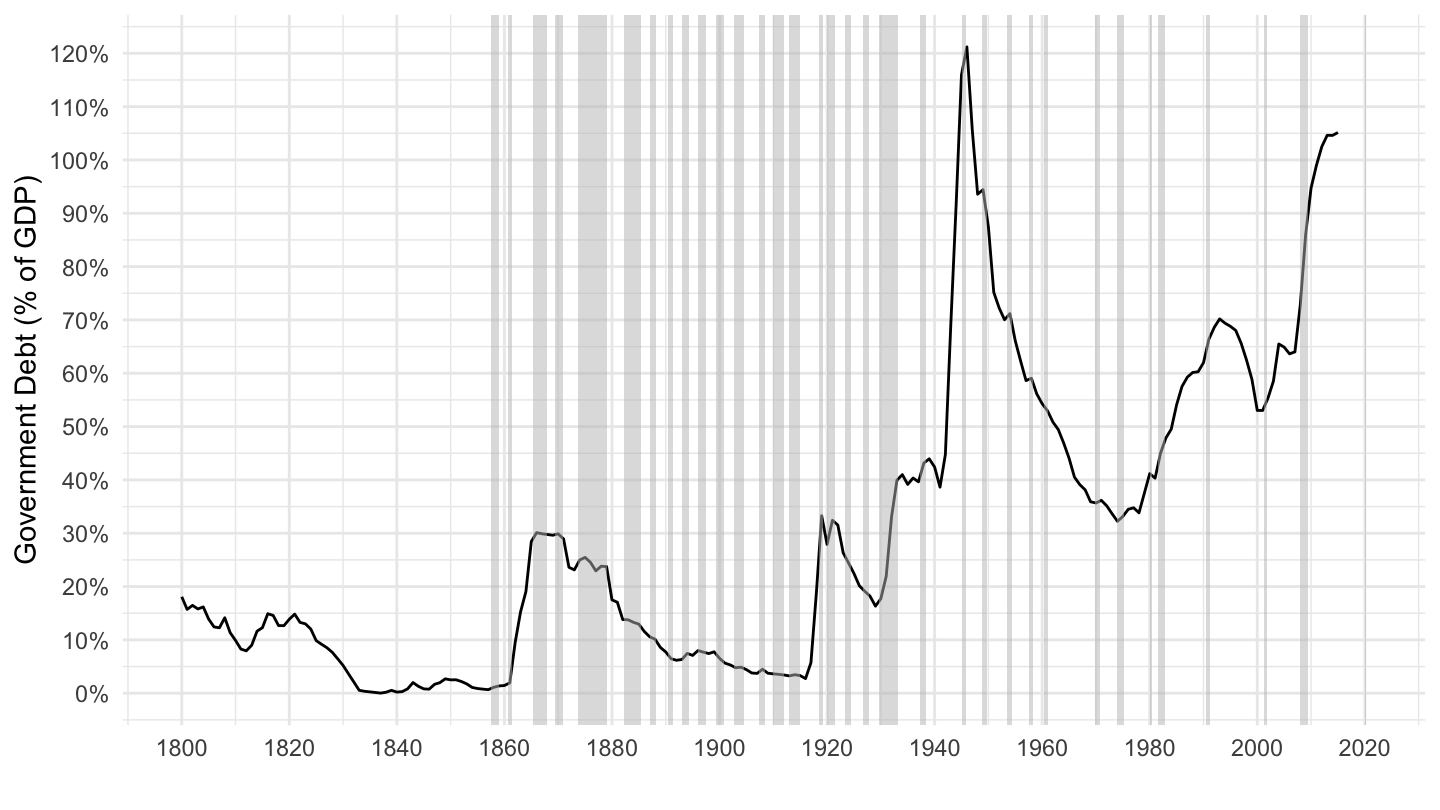

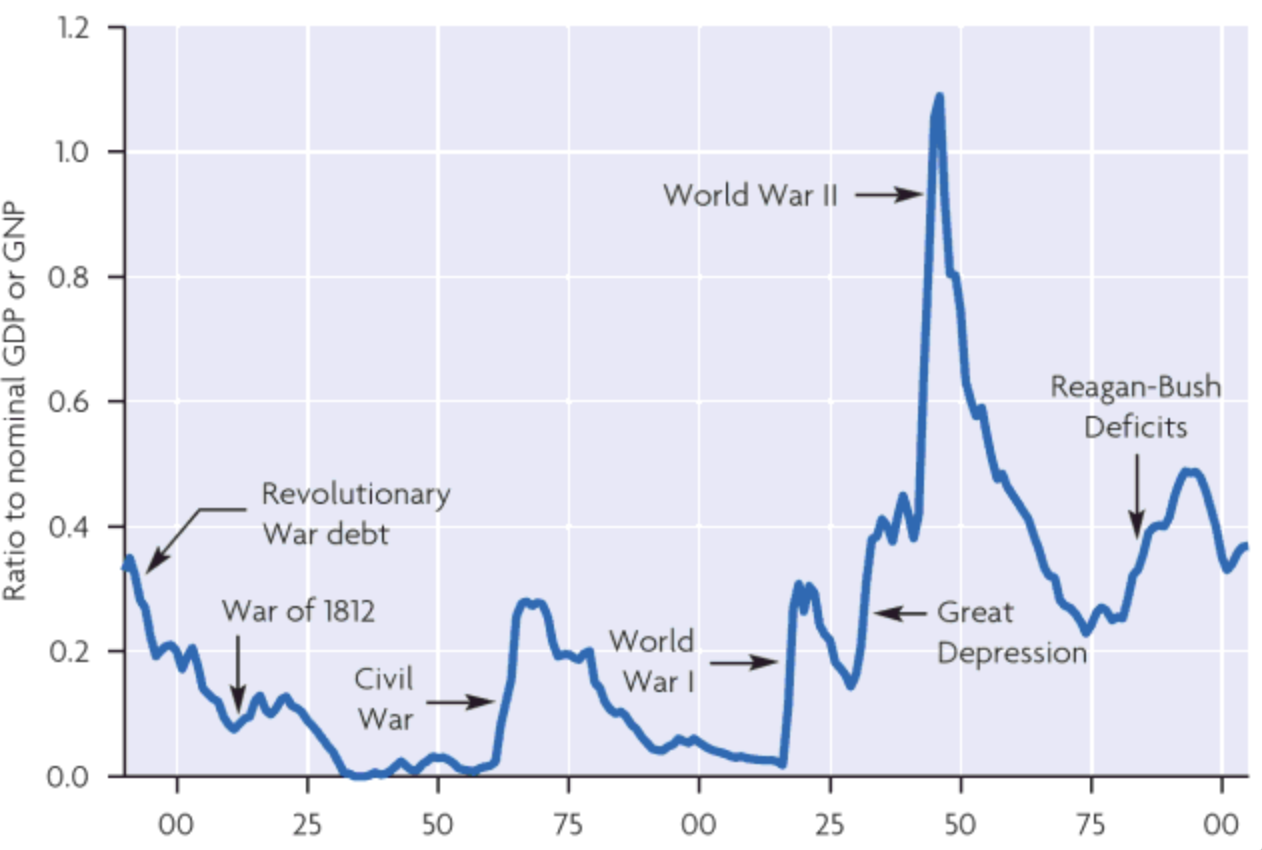

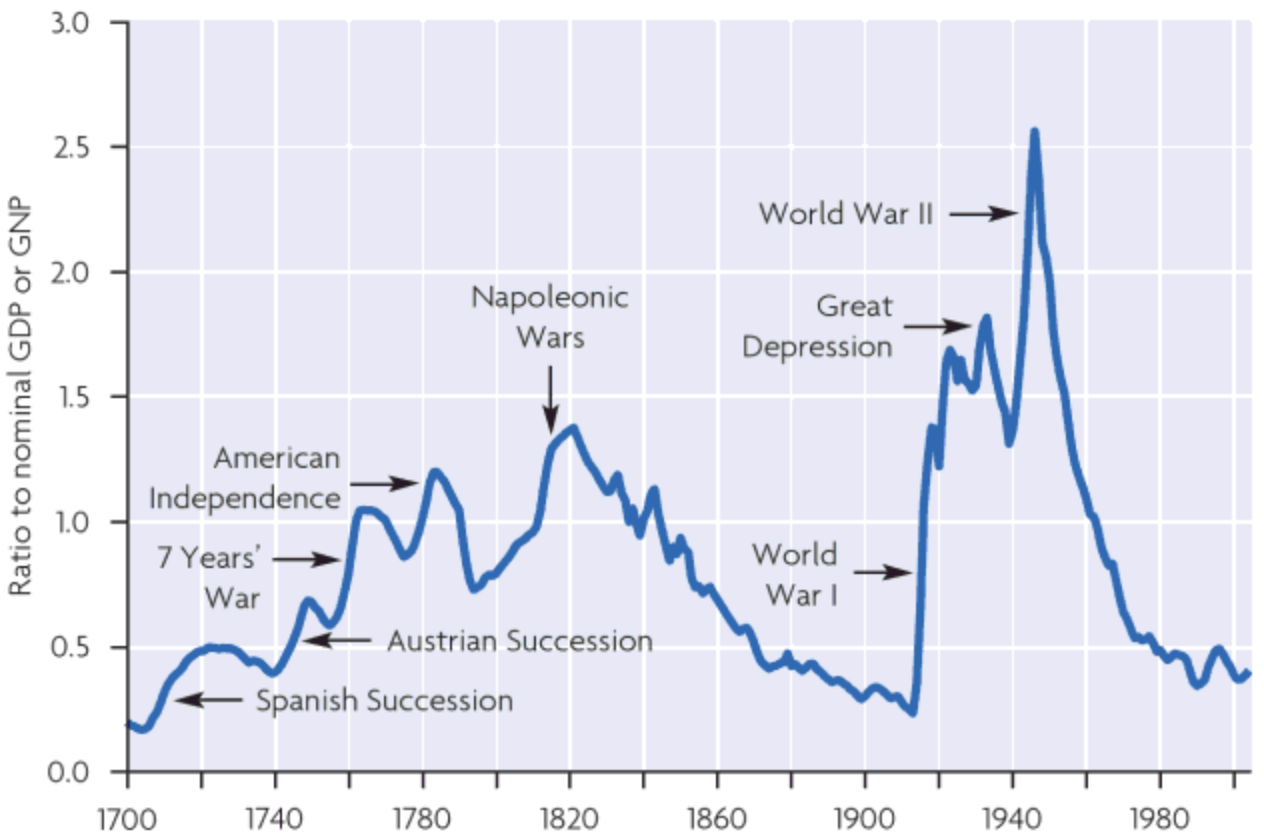

Public Debt and Wars

Context

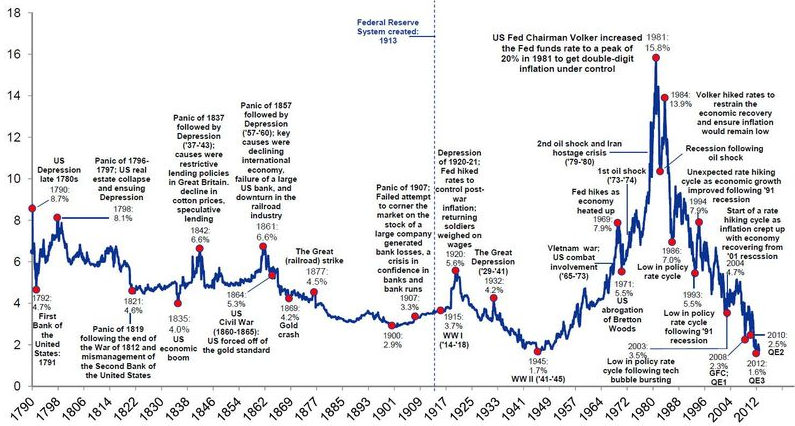

Historically, large increases in public debt have been used to finance wars.

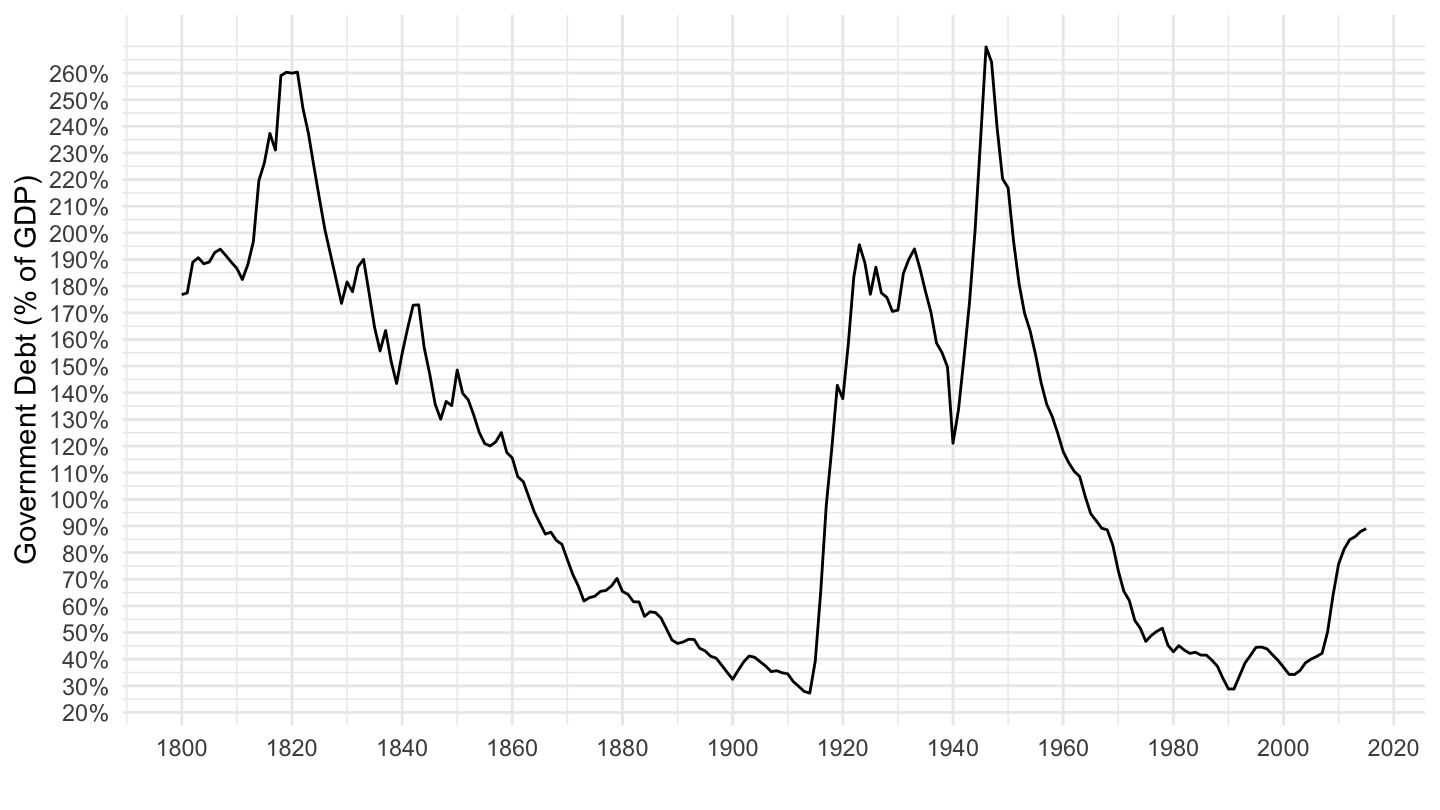

United Kingdom in 1820: 260% of GDP.

1820-1910: Public debt = 260% of GDP to 30% of GDP.

As we shall see later, this is perhaps also the cause of excess savings at the end of the XIXth century, start of the XXth century.

Alternative to taxation of wealth during wars: buying bonds is “voluntary.”

United States (Source: Barro)

Costs of U.S. wars from How much

-5ed7.jpg)

United Kingdom (Source: Barro)

Buy Victory Bonds

Government Debt to Finance the War

Buying a bond is no sacrifice

r and g, Sustainability of Public Debt

Assumptions

We denote everything in terms of goods (that is, in real terms), to avoid thinking about the complicated issues surrounding inflation.

\(G_t\) : government spending at period \(t\).

\(T_t\) : taxes in period \(t\).

\((G_t-T_t)\) the government (primary) deficit in period \(t\), which is the excess of government expenditures over taxes levied by the government.

When \(G_t-T_t>0\), there is a primary deficit in the budget, so that the government must borrow.

When \(T_t-G_t<0\), there is a primary surplus in the budget.

Law of motion

If the interest rate that the government pays is given by \(r_t\), then the law of motion of government debt is given by: \[B_{t}=(1+r_t)B_{t-1}+G_{t}-T_{t}.\]

Total government deficit, which is equal to the change in government debt \(\Delta B_{t}\), is equal to the sum of interest payments and the primary deficit \(G_{t}-T_{t}:\) \[\text{Deficit}_{t}=\Delta B_{t}=B_{t}-B_{t-1}=\underbrace{r_tB_{t-1}}_{\text{Interest Payments}}+\underbrace{G_{t}-T_{t}}_{\text{Primary Deficit}}\]

Law of motion for debt to GDP ratio 1/2

From the above equation, the evolution of the debt to GDP ratio \(B_{t}/Y_{t}\): \[\frac{B_{t}}{Y_{t}}=(1+r_t)\frac{Y_{t-1}}{Y_{t}}\frac{B_{t-1}}{Y_{t-1}}+\frac{G_{t}-T_{t}}{Y_{t}}.\]

Let us denote the debt to GDP ratio by \(b_t\): \[b_t \equiv \frac{B_t}{Y_t}.\]

Law of motion for debt to GDP ratio 2/2

Therefore: \[b_t = (1+r_t)\frac{Y_{t-1}}{Y_{t}}b_{t-1}+\frac{G_{t}-T_{t}}{Y_{t}}.\]

Assuming that GDP grows at rate \(g\), we have that: \[\frac{Y_t}{Y_{t-1}}=1+g.\]

Therefore: \[\boxed{b_t = \frac{1+r_t}{1+g}b_{t-1}+\frac{G_{t}-T_{t}}{Y_{t}}}.\]

Condition for Sustainability of Public Debt

Imagine that all future primary surpluses were equal to zero after \(t=t_0\), that is: \[\text{for all }t\geq t_{0},\quad G_{t}=T_{t},\]

Assume that interest rates are constant after \(t \geq t_0\): \[r_t=r.\]

Debt to GDP Ratio

We then have: \[\text{for all }t\geq t_{0},\quad b_t = \frac{1+r}{1+g}b_{t-1}.\]

Debt to GDP ratio would be given by: \[\boxed{\text{for all }t\geq t_{0},\quad b_t=\left(\frac{1+r}{1+g}\right)^{t-t_{0}}b_{t_0}}\]

3 possible cases

There are three possible cases, depending on how r (real interest rate) and g (real growth rate) compare:

If \(r<g\) - a situation called dynamic inefficiency - the debt to GDP ratio goes to 0. (Indeed, when \(a<1\), \(a^{t}\to 0\) when \(t \to +\infty\).) Therefore, the debt to GDP ratio goes to zero.

If \(r=g\), the debt to GDP ratio stays constant. Then, the debt to GDP ratio stays constant.

If \(r>g\), a situation called dynamic efficiency, the debt to GDP ratio goes to infinity. Indeed, when \(a>1\), \(a^{t}\to+\infty\) when \(t \to +\infty\). Then, the debt to GDP ratio goes to infinity. Therefore, we have a snowballing of government debt.

U.S.: Dynamically inefficient

Which of these three cases is relevant for the U.S. economy? \(=\) Is public debt sustainable in the U.S.?

How do the real interest rate \(r\) and the growth rate of GDP \(g\) compare?

Up until now, I would argue that it’s fair to say that \(r<g\).

Therefore, the snowballing effect of government debt actually is negative. So a Ponzi Scheme is much easier to run in these conditions.

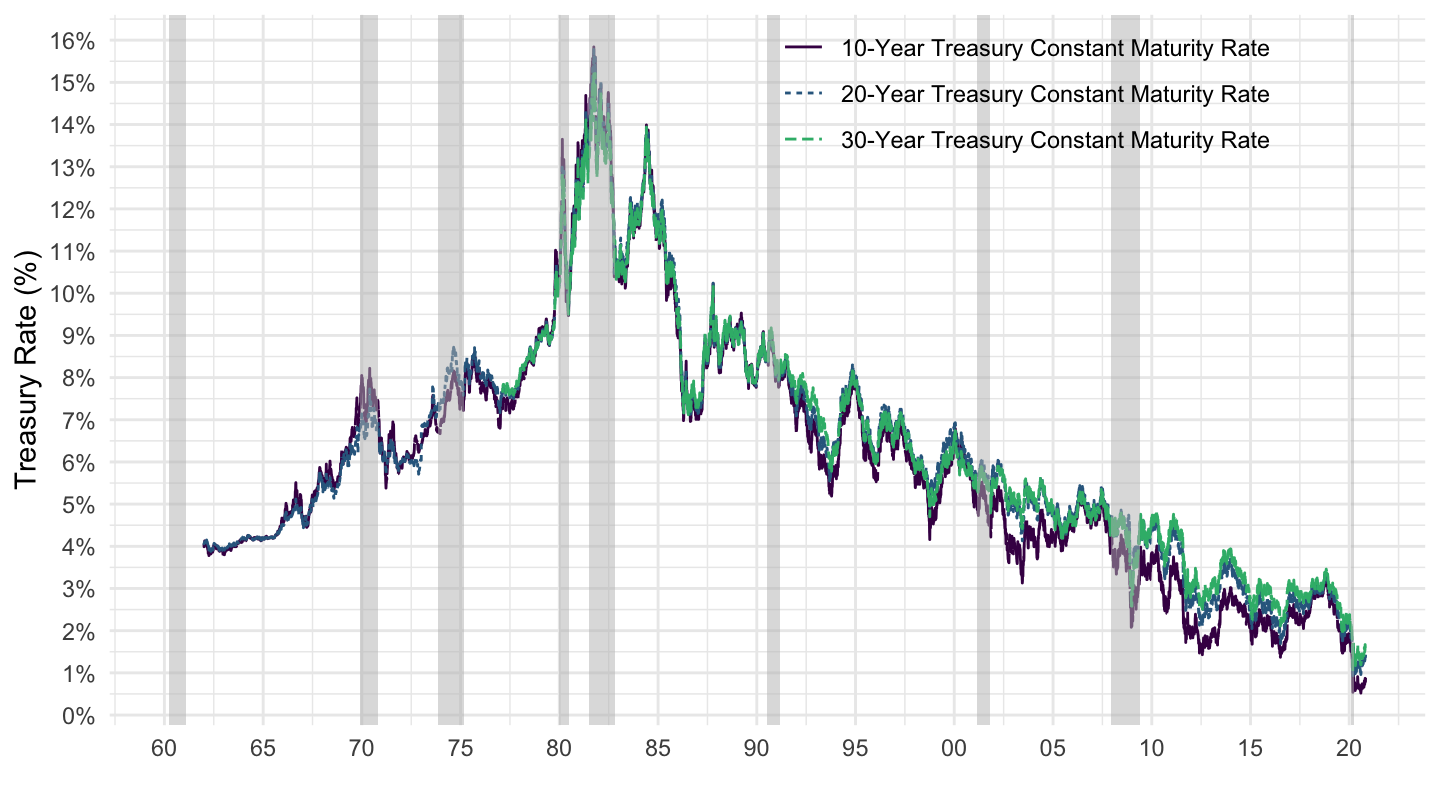

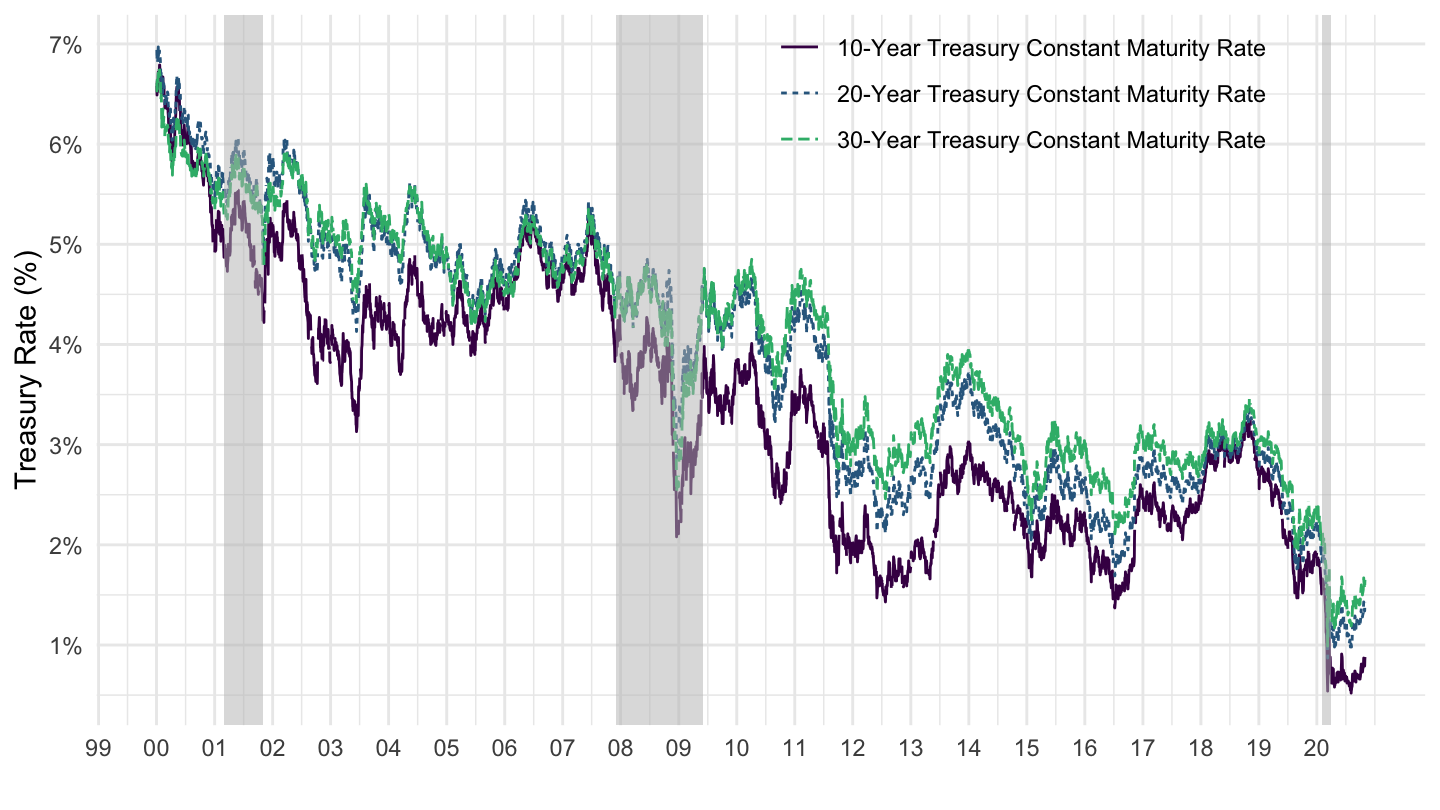

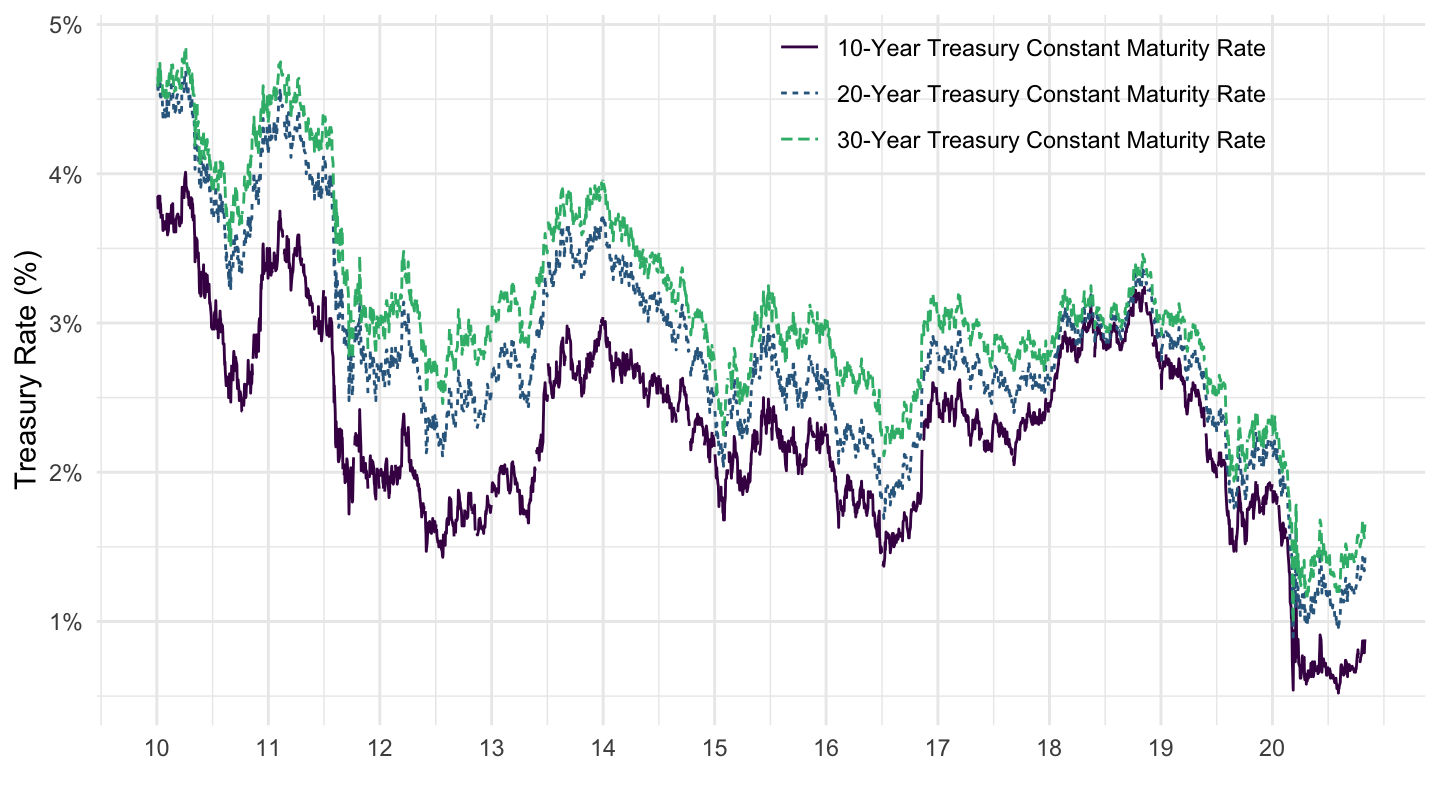

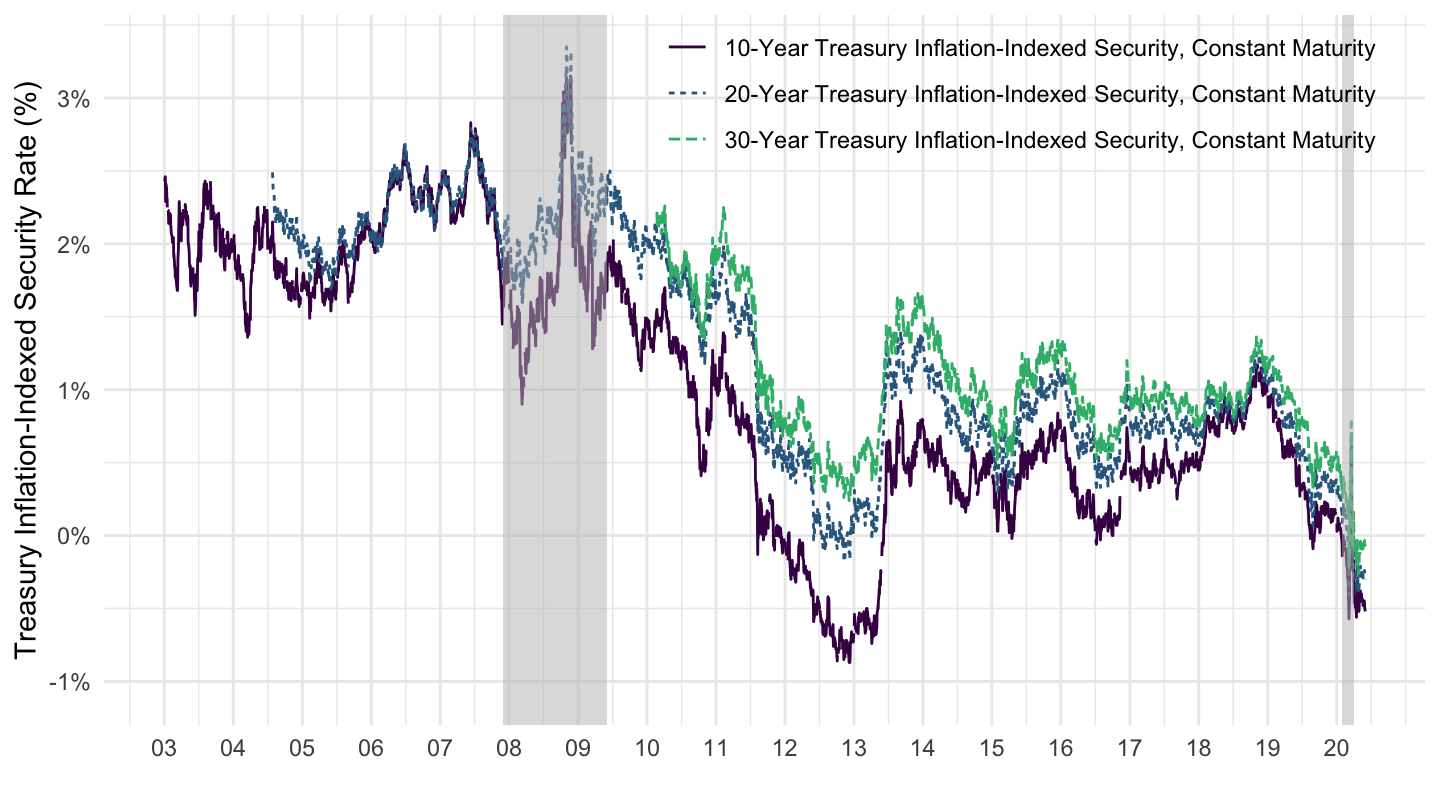

U.S. 10Y, 20Y, 30Y Treasury Rate

Since 2000

Since 2010

Treasury Inflation Protected Securities

U.S. Longer Run

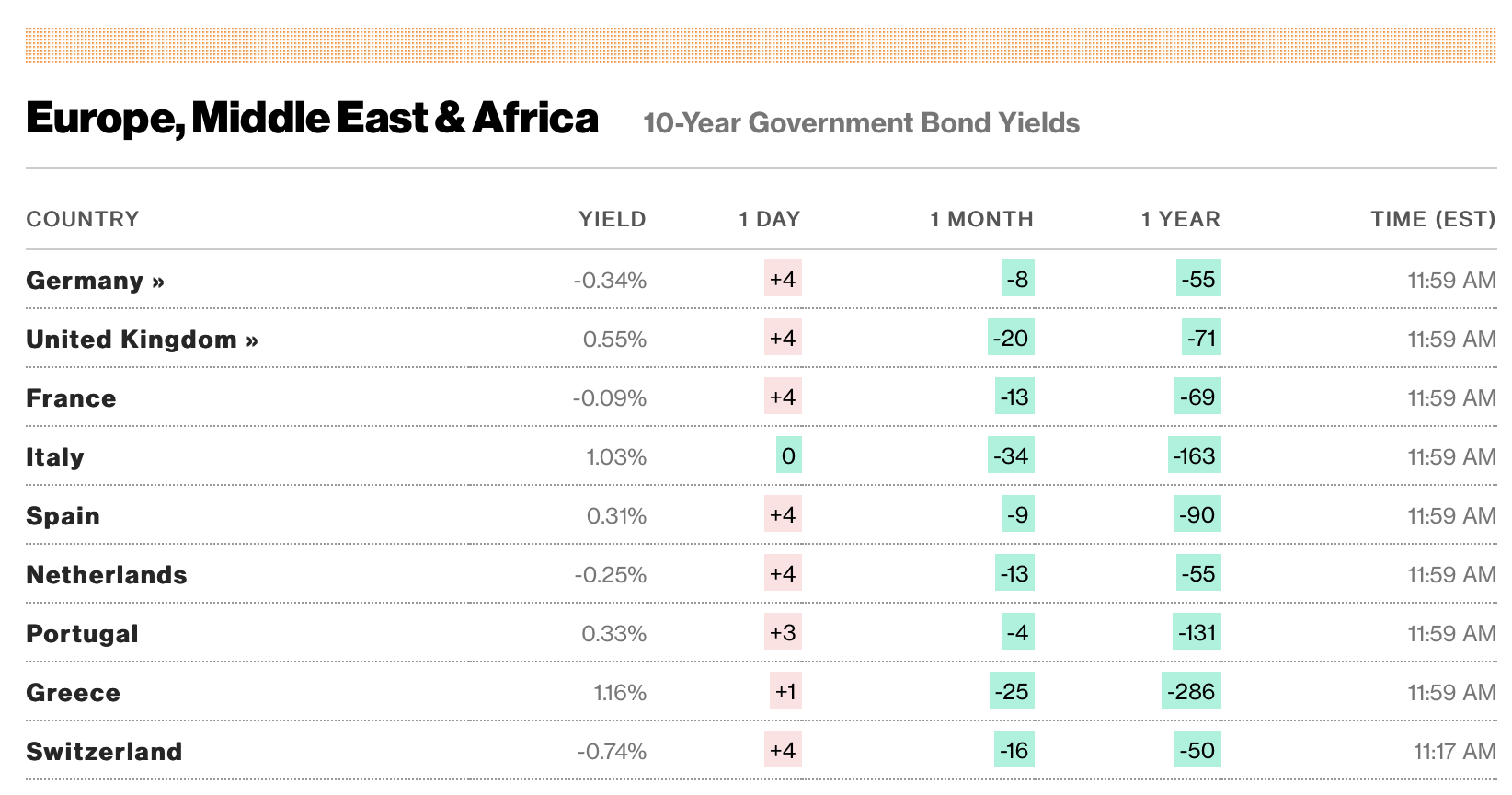

10-Year Government Bond Yields in Europe

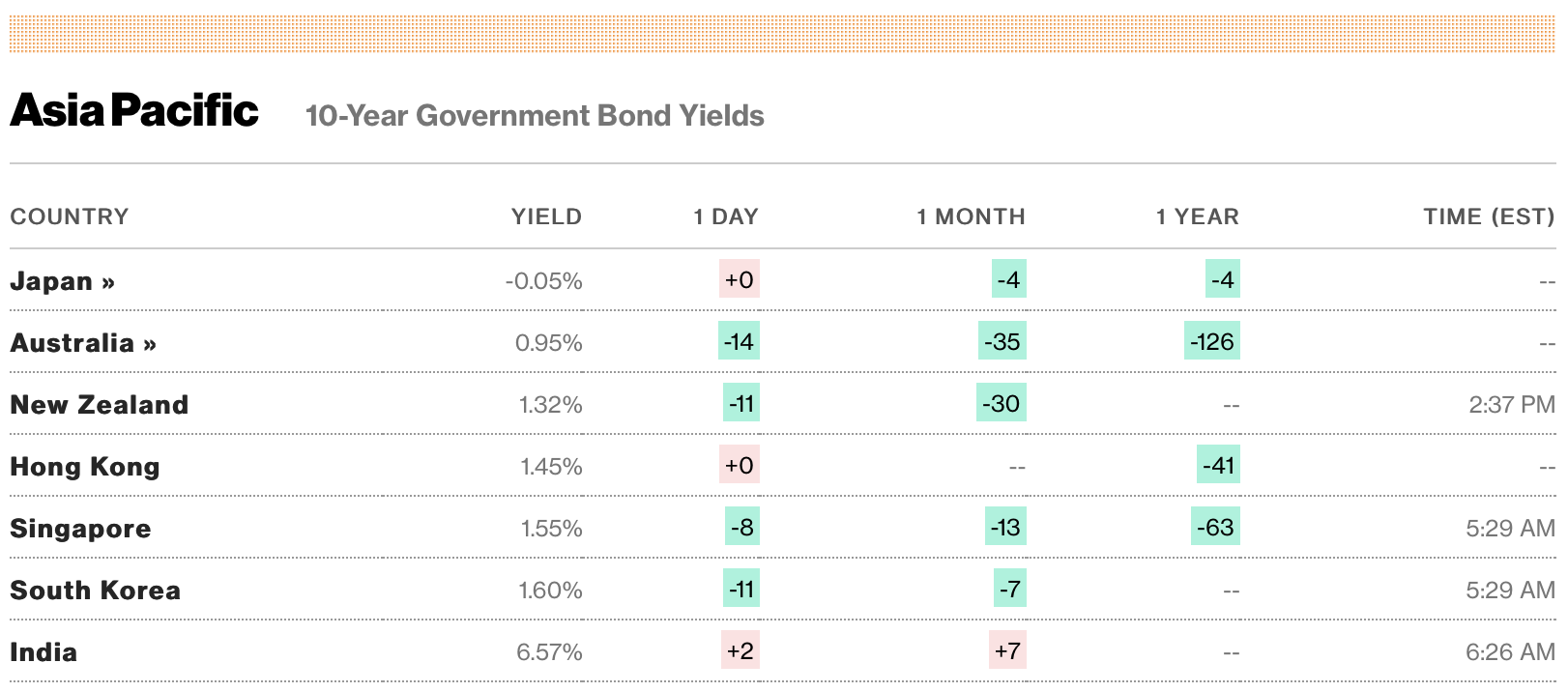

10-Year Government Bond Yields in Asia

r-g across Countries

2007-2009, 2010-2013 and public debt

2007-2009, 2010-2013

Stimulus package was implemented in the U.S., however fiscal policy turned more restrictive starting in 2010.

2011: Greek debt crisis. Europe implemented a series of austerity plans in 2011-2013.

Many economists were on the side of advocating in favor of more austerity:

Alan Greenspan, Robert Barro, etc.

But also Olivier Blanchard, etc.

Few people arguing on the other side: Paul Krugman (very forcefully).

Alan Greenspan: U.S. and Greece

ECB

Mario Draghi’s July 2012 “Whatever it takes”

IMF’s 10 commandments

IMF’s 10 commandments

Arguments for government debt

Public debt and heresy

Disclaimer: on public debt, I am less worried than most economists. Many economists, policymakers are worried about excessive public debt.

Full disclosure: I have a stake in this! I defended my ph.D. in July 2013, arguing that government debt was actually useful to remedy excess saving, and that more public debt was needed. This used to be controversial, particularly in 2010-2013 when many policymarkers were pushing for austerity in Europe, following the Greek government debt crisis.

Still, I am going to give you arguments in favor of public debt, because I believe that public debt is not such a big problem.

In fact, I think that our economic difficulties would be even greater without it, and that more public debt in fact a good thing. I think that Trump’s recent stimulus shows this once again.

Should the average level of public debt be zero?

Many economists think that public debt is an issue.

According to New-Keynesian economics, deficits should rise during bad times, but they should fall during booms. Indeed, for New-Keynesians, public debt is useful only to reduce the volatility of GDP.

According to Neoclassical economics, public debt is bad because it crowds out useful capital accumulation.

I will now cite two authorities:

Alesina, Favero, Giavazzi in their recently released book Austerity.

Ricardo Reis, a famous macroeconomist at the London School of Economics.

Petrodollar recycling - Graeber (2011)

Quote from Austerity

From Austerity, by Alesina, Favero, Giavazzi:

Widely Shared View

This view is widely shared, even among (mainstream) Keynesians. Reis (2018) - “Is Something Really Wrong with Macroeconomics?”

Two “dovish” speaches: 2013 and 2019

In November 2013 Larry Summers, at the IMF Fourteenth Annual Research Conference in Honor of Stanley Fischer, argued in favor of “secular stagnation,” or the idea of an excess of savings over investment.

In his January 2019 address to the AEA, “Public Debt and Low Interest Rates,” Olivier Blanchard (2019) argued that the costs of public debt were probably lower than previously believed:

Although he did not explicitely push for more government debt, this is how it was received.

He did not say that there were excess savings but he did emphasize the importance of the fact that \(r < g\).

On my side, I agree more with Larry Summers’ secular stagnation view.

Secular stagnation

With deficient aggregate demand, and too much savings, the only alternative is asset pricing bubbles (see Summers (2015)).

More later on theoretical controversies.

Summers’ Secular Stagnation Speech

Important quote: is Keynesian economics about fluctuations?

In particular, at 6:24, he says:

Or is it about increasing the average level of economic activity?

I also agree with Larry Summers here

Reis (2018)

Reis (2018): “Most macroeconomists support countercyclical fiscal policy, where public deficits rise in recessions, both in order to smooth tax rates over time and to provide some stimulus to aggregate demand. Looking at fiscal policy across the OECD countries over the last 30 years, it is hard to see too much of this advice being taken. Rather, policy is best described as deficits almost all the time, which does not match normative macroeconomics.”

I think in contrast that because of the paradox of thrift, GDP would be even lower with all that government debt.

In my view, policymakers have been right to disregard the advice from (mainstream) “normative macroeconomics.”

Should you worry about Public Debt?

I don’t: interest payments are lower than 2% of GDP in the U.S.

Public debt is a Ponzi scheme

Ponzi scheme

With a Ponzi scheme, you promise high returns to investors. You pay these returns using the contributions of new contributors to your fund.

Of course, at some point, it must run out. Indeed, you run out of investors to convince, and the game stops.

Or does it? Imagine that you can tap previous investors, and their saving grows at a rate higher than the promised return.

Then you can maintain the Ponzi scheme.

One interpretation of public debt

One interpretation of public debt is that it corresponds to “voluntary expropriation of the rich.”

The rich maybe save largely because “they do not know what to do with their money.”

From the New York Times, Why Don’t Rich People Just Stop Working?

“Literally, in a matter of weeks, certainly a couple of months, the phone calls have had a different tone to them,” Mr. Rickards said. “What I’m hearing is, ‘I’ve got the money. How do I hang on to it?’ ‘Are gold futures going to hold up or should I have bullion?’ ‘If I have bullion, should I put it in a bag in a private vault?’”

“It’s a level of concern that I’ve never heard from the superrich,” he said. “The tone of voice is, ‘I need an answer now!’”

Wealth Taxation and Public Debt

Option 1: Consider a wealthy family who accumulates wealth, passes it on to their children, and never consumes it. (because their children are successful too, they never need to consume the corresponding wealth) That wealthy family accumulates wealth in the form of government debt, which is then passed on from generation to generation.

Option 2: Assume now that this wealth is instead taxed at a high rate (for example, under Elisabeth Warren’s wealth tax plan), and that the proceeds are used to repay the public debt.

The two options are perfectly equivalent, in terms of macroeconomic aggregates, as well as individual consumption. The only difference is that the rich are probably more unhappy with option 2: they prefer voluntary expropriation (which they choose by never consuming) than expropriation imposed by the state.