On Insee’s blog post ‘Yes, Insee does take housing into account in inflation!’

In an Insee Blog1 entitled “But yes, Insee does take housing into account in inflation”, the chief of staff to the Director General of Insee responded on February 4, 2020, to Emmanuel Todd (2020)’s book “The Struggles of Classes in France in the 21st Century”, which challenged Insee’s calculation of price indices (and therefore living standards), particularly the insufficient inclusion of housing in these indices (Ourliac (2020))2. Several arguments were put forward to defend Insee’s choices, in particular the low weight of 6% assigned to rents in the French Price Index.

About the “international methodological manual”

The Insee Blog first uses an argument from authority: the choices of the statistical institute would not be specific to France; they would follow the recommendations of an “international methodological manual” (IMF (2020)). The Blog thus states:

Insee’s choices are not specific to France: at the international level there exists a methodological manual prepared by all of these organizations, and at the European level a regulation that define how to calculate the CPI, shared by all of Insee’s counterparts abroad.

This passage implies that the exclusion of owner-occupied housing in particular—the main subject of the Blog post—would be part of the recommendations in international methodological manuals. However, this is not the case: the methodological manual referred to in the Blog is publicly available online. And nowhere in its 509 pages does it recommend excluding owner-occupied housing from the calculation of the Consumer Price Index (Indice des Prix à la Consommation), i.e., to follow Insee’s method… On the contrary, this manual presents five different methods for addressing the problem of owner-occupied housing in the Consumer Price Index: four ways of including it, and a fifth method consisting of not including it. It does not make a recommendation.

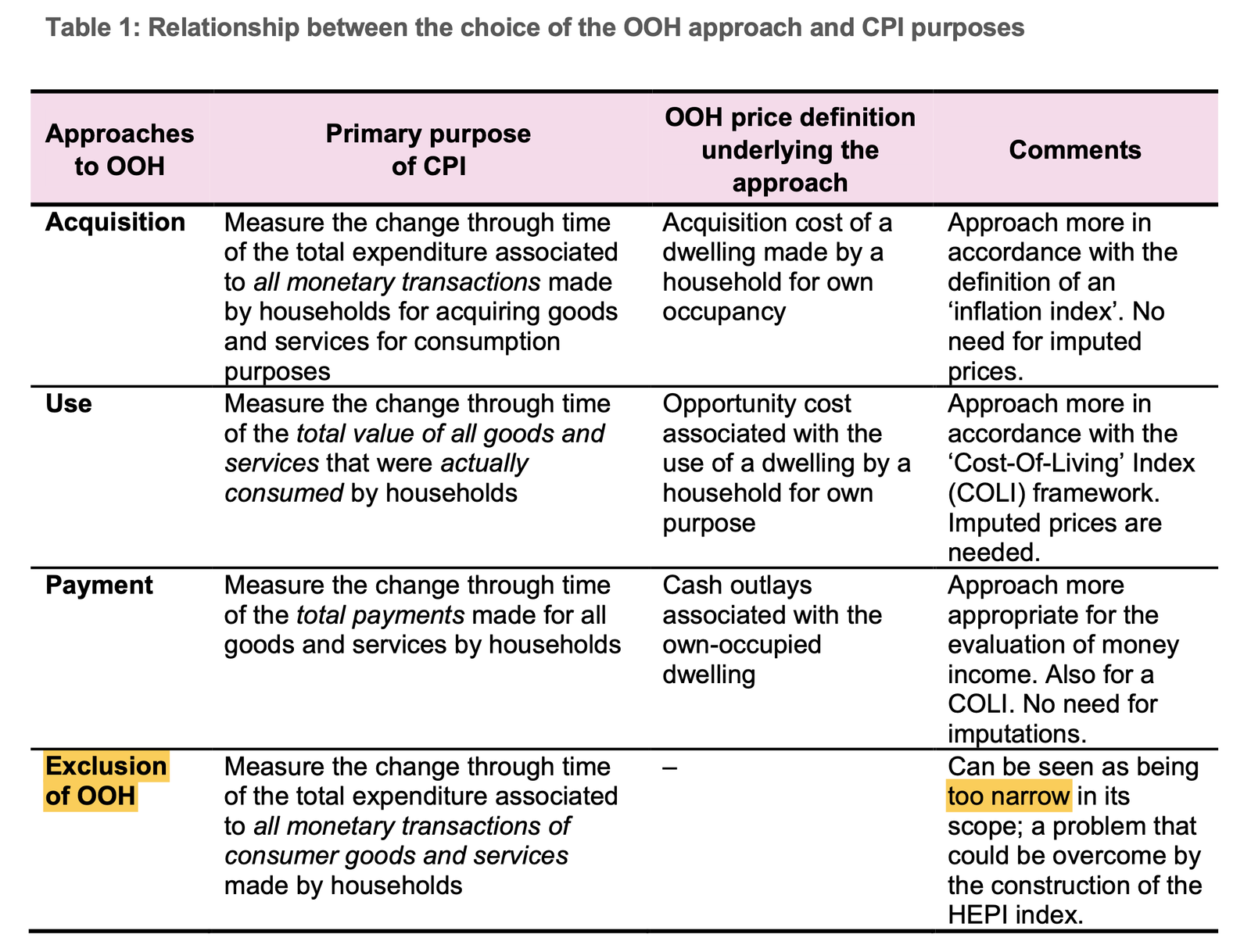

Moreover, the methodological manual mentioned is not the most comprehensive on this specific issue of including housing in the Consumer Price Index: there exists a manual dealing more specifically with the question of including housing costs in the Consumer Price Index, published by Eurostat (Eurostat (2017)) and entitled “Technical Manual on Owner-Occupied Housing Price Indices and House Price Indices.” And what does this manual say? It is rather critical of the non-inclusion of housing in the Price Index adopted by French official statistics, as can be seen in Figure 1 below (sorry for the English): according to this manual, not including owner-occupied housing can be considered as leading to an index that is too “narrow” in scope, and elsewhere in the manual it even recommends using this method only in the case of an insufficient statistical apparatus. And indeed, France is one of the few countries in Europe not to include owner-occupied housing in the Price Index for its national index.

Furthermore, as can be seen in this table, the choice to exclude owner-occupiers’ housing expenditures from the CPI (Indice des Prix à la Consommation, IPC) would correspond to the choice to account for only “monetary transactions” in the CPI. Yet the French CPI does not meet this requirement either. Indeed, Insee includes in the CPI health expenditures reimbursed by social security, which are not part of “household consumption” but rather “individualizable public administration consumption.” This has no theoretical justification (in that case, why not also include other individualizable public consumption services, which are “free” for the user: education, culture, social action?). Thus, the scope of the CPI does not even correspond to “monetary transactions” as described here in the Eurostat manual, which could at least have justified the exclusion of imputed rents — for example, if the CPI were used solely for monetary policy, and not as a cost-of-living index. The French CPI thus appears as a hybrid index, which to our knowledge has no equivalent. Moreover, the inclusion of health expenditures also contributes to underestimating inflation in France, because the prices of reimbursed medicines tend to fall, particularly thanks to “quality effects.” One can measure this underestimation by comparing it to the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP, Indice des Prix à la Consommation Harmonisé, IPCH) calculated at the European level, which does not have this problem (the difference is about +5% since 1996).

The Blog also claims that:

Insee’s choices are not specific to France.

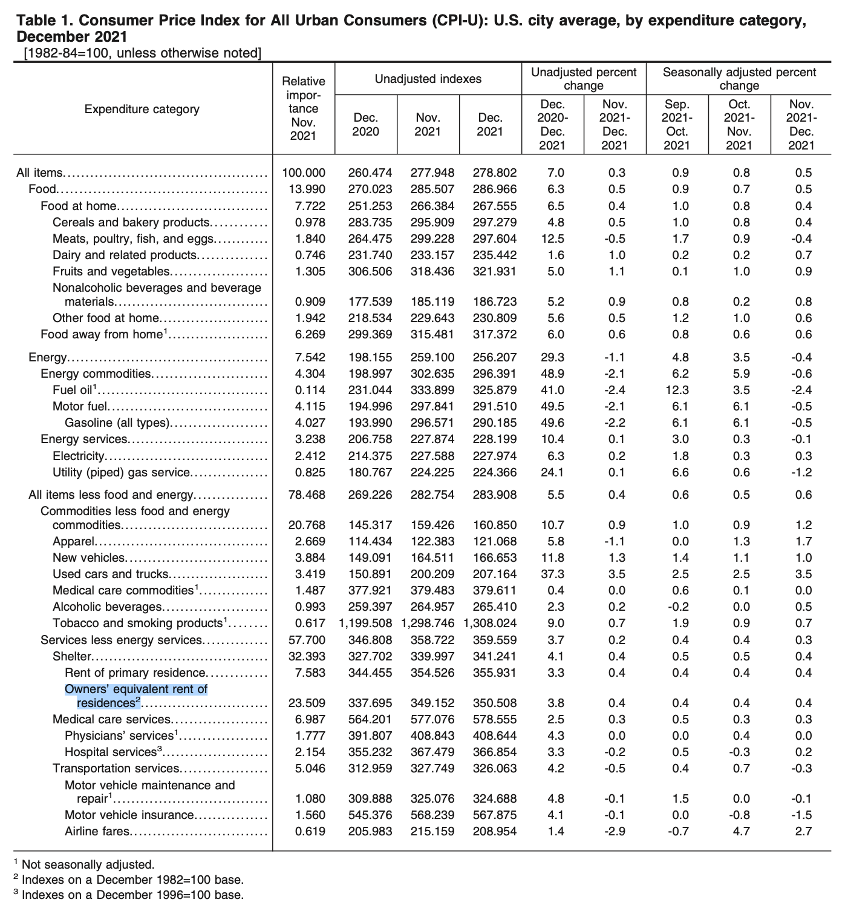

Again, an examination of what is done elsewhere reveals that the complete exclusion of the cost of owner-occupied housing is a very minority choice internationally: most countries (for example, the United States or Germany) include imputed rents in their Consumer Price Index. In the U.S. CPI, imputed rents are included, as can be verified in the latest press release from the Bureau of Labor Statistics regarding the price index and reproduced in Figure 2: the Consumer Price Index for Urban Households includes imputed rents at a weight of 23.5%, which, added to the 7.6% for actual rents, makes 30.1%.

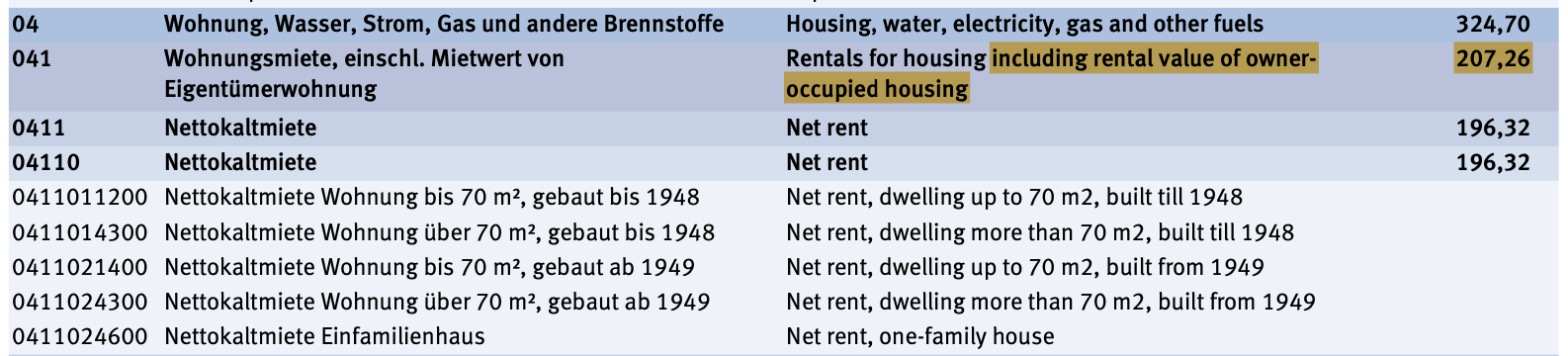

Similarly, the weight of rents is 20.7% in the German price index, and it includes the imputed rents of owner-occupiers, which can be verified by consulting the latest press release from the German statistical office Destatis regarding the price index for January 2022, reproduced in Figure 3. In France, if imputed rents were included, the weight of rents in the CPI would also be about 21%, and not 6%.

Insee would also rely on a European-level regulation, which again would justify its choice. It is indeed correct to say that at the European level, Eurostat’s Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP, IPCH) does not for the moment include the cost of housing for owner-occupiers (imputed rents). But this is not proof of a European consensus on the subject, which does not exist: as Eurostat’s methodological manual on this subject details, excluding owner-occupied housing from the CPI is considered a “narrow” method by Eurostat itself. This is why the inclusion of owner-occupied housing in the CPI has long been planned, i.e. since the HICP was established, and an experimental index in this direction has recently been calculated at the European level. Finally, and most importantly, as already noted, most European countries include owner-occupied housing in their consumer price index, first and foremost Germany. The non-inclusion of imputed rents in the HICP is therefore not a sign of European consensus on this subject, but probably of a lowest-common-denominator logic. (Without having more precise information on this point, one can imagine that France did not push in this direction.) Finally, the objective of the HICP is not in any case the same as that assigned to the national CPI: the HICP serves monetary policy in the Eurozone, and is not intended to be used for indexation purposes. Destatis explains thus the difference between a national CPI, which is used mainly for compensation and cost-of-living measurement, and the HICP, which measures inflation for monetary policy purposes.

The suspicion of interference by the Ministry of Economy and Finance over Insee in the calculation of inflation is ridiculous; it primarily reflects a total ignorance of the conditions under which the methodology of the CPI is developed.

Since neither the methodological manuals nor the aforementioned regulations are as definitive as the Blog claims — quite the contrary — and since France appears rather isolated on this subject at the international level, it does not seem a priori impossible that the choice of one method over another is made on political grounds, or at least not strictly on the theory of price index construction.

An objective could, for example, be to save on social expenditures, since the Consumer Price Index is used to index pensions, minimum social benefits, etc. The goal of saving money is not necessarily objectionable in itself — but at the very least it should be acknowledged and, if necessary, debated democratically. Furthermore, one may wonder whether the underestimation of the official Consumer Price Index is a good way to achieve budgetary savings, and whether it would not be healthier and more transparent to explicitly assume official de-indexations, if that is the intended political objective. In any case, is the suspicion of interference really as “ridiculous” as claimed, and can one truly assert that it reflects a “total ignorance”? # The Purchase of a Dwelling as Investment Expenditure

Having reviewed the arguments from authority, let us now turn to the substantive reasoning. Is it economically justified to exclude owner-occupied housing from the CPI (Indice des Prix à la Consommation, IPC)? According to the Blog, the decision not to include rents in the CPI would be logical, insofar as the purchase of a dwelling would correspond to investment expenditure. Thus, Insee’s Blog asserts that owner-occupiers who no longer have mortgage payments would have no housing expenses other than utilities (water, gas, electricity).

For 8 out of 10 households (including 4 tenants and 4 homeowners with no more mortgage payments), housing expenses are exclusively consumption expenditures (rent, water, gas, electricity, routine maintenance), and are therefore fully accounted for in the CPI;

According to this statement, the 40% of owners without mortgage payments would see their housing costs fully accounted for in the CPI, since for them, these would consist only of utilities — that is, expenditures on water, gas, electricity, and routine maintenance. This, however, is a reasoning error. Indeed, the occupant of a dwelling does “consume” the rent they would have to pay if they were tenants of the same dwelling: by occupying the dwelling they own rather than renting it, they forego an income, which is the strict economic equivalent of a rent, and which is in fact a consumption expenditure. Another way to see this is that they also forego income compared to a stock market investment or a life insurance policy, in which case they would receive dividends or interest each year. Moreover, while they do not pay rent, they must in return pay for maintenance and improvement works on the dwelling, contribute to building association funds for shared works, etc. Indeed, Insee calculates each year the “imputed rents” that owner-occupiers implicitly pay to themselves, which are treated as consumption expenditures in the national accounts.

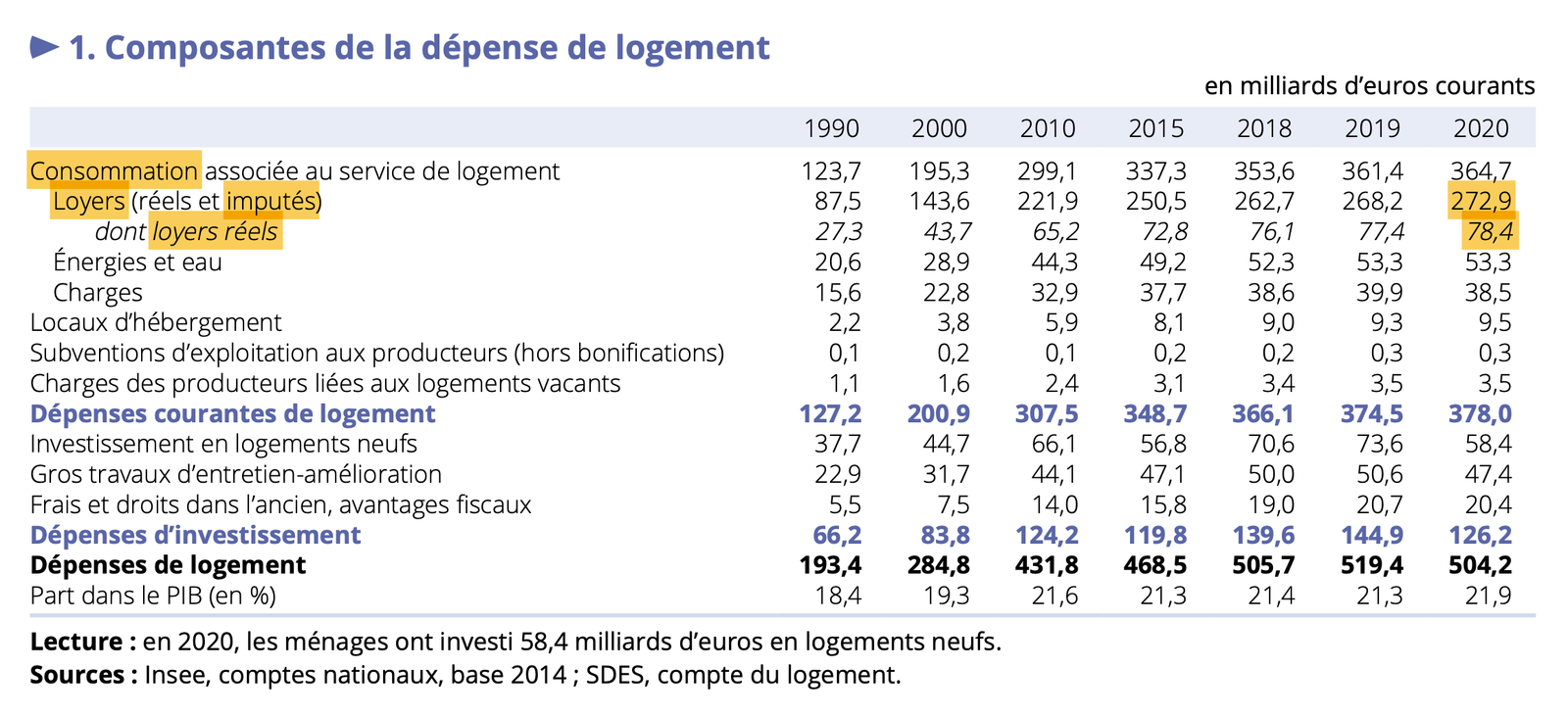

For example, as shown in Figure 4 in the table below from France, Portrait Social 2021 (p. 201), actual and imputed rents amounted to €272.9 billion in 2020, of which €78.7 billion were actual rents and €194.2 billion imputed rents — i.e. about 2.5 times more imputed than actual rents. These rents are presented as “consumption associated with housing services,” making it difficult to justify their exclusion from the Consumer Price Index. If actual rents weigh 6% in the CPI, then imputed rents should weigh about 2.5 × 6 = 15%, and the total of actual and imputed rents 21%, which is exactly what we observe in Germany.

This choice to assign an imputed rent to owner-occupiers and to treat it as consumption may appear theoretical, but it is anything but arbitrary: it even appears to be the only possible choice. Consider two dwellings, A and B, identical in all respects, owned respectively by Mr. A and Mr. B. Does the consumption of housing differ if Mr. A rents B’s dwelling and vice versa, or if each occupies their own dwelling? No, of course not! Yet if we follow Insee’s reasoning, housing consumption would be zero in one case, and two rents in the other3. Likewise, it is hard to see why the method of calculating the Consumer Price Index should differ between the two cases.

Including Imputed Rents: A Negligible Effect on the Measurement of Inflation?

The Blog then asserts that, in any case, increasing the weight of housing in the CPI (Indice des Prix à la Consommation, IPC) to take imputed rents (loyers imputés) into account would have only a very limited effect on the measurement of inflation:

Any convention can be questioned (and should be, regularly, since economic thought, social norms, or the socio-economic context prevailing at the time of their adoption also evolve). In the case of housing expenditures, one could, for example, wish to bring tenants and owners closer together, or even include the purchase of dwellings. Insee recently did so transparently, with a publication that addresses all these questions; it shows in particular that, beyond theoretical and methodological controversies, different conventions would have only a negligible effect on the measurement of inflation.

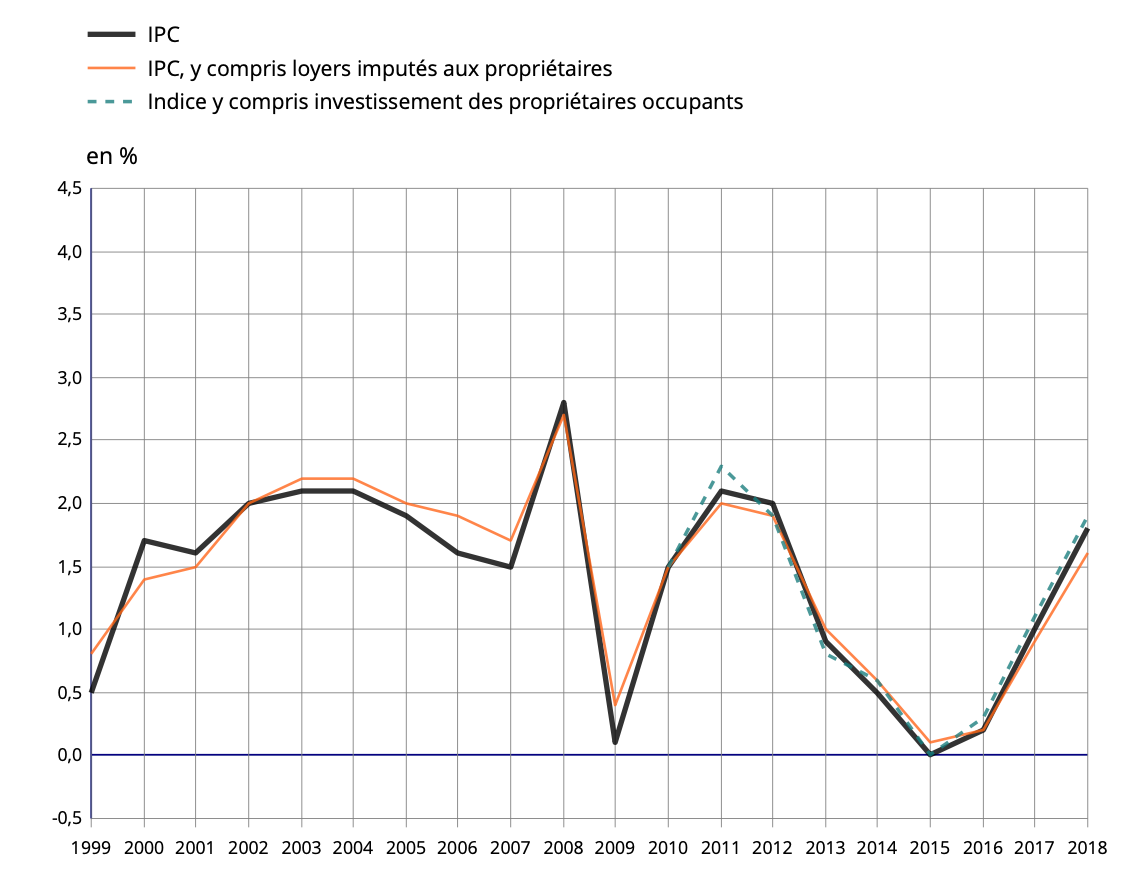

This Insee publication (Leclair, Rougerie, and Thélot (2019)) would in itself deserve a separate discussion, and another note. A few quick remarks, however. First, neither the choice of the period nor the presentation of results is neutral: this publication, for example, claims that rents evolve at a rate similar to that of the CPI, while presenting a graph that makes visual comparison difficult — see Figure 5. To the naked eye, there are a few tenths of a percentage point of difference between the CPI and the CPI including imputed rents, but the small gap is supposed to attest to the idea that rents evolve in roughly the same way as the CPI.

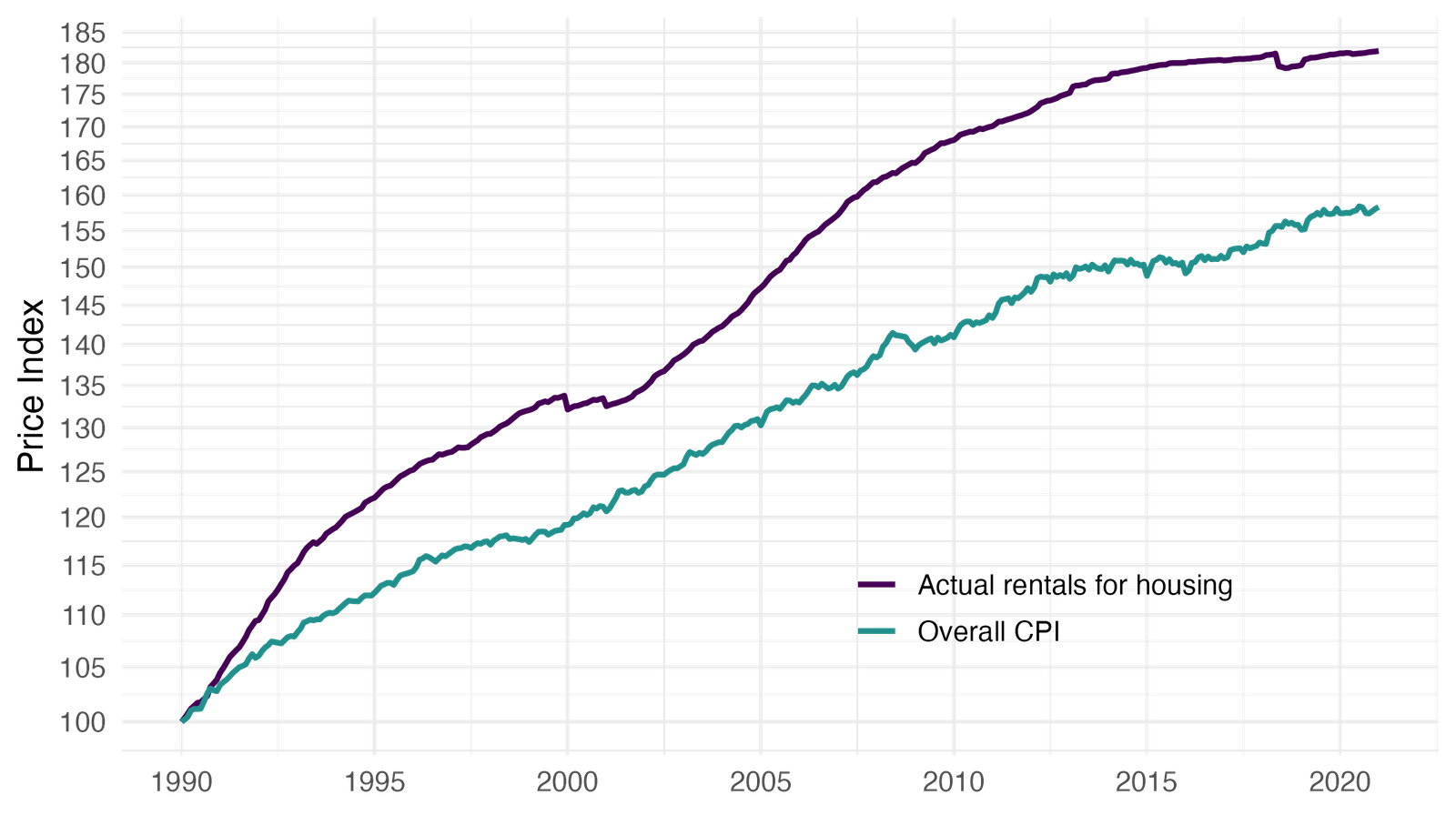

If one examines the price index since 1990, as provided by Insee, and compares it to the evolution of actual rents (loyers effectifs), it is far from obvious that rents have increased at the same pace as the CPI — see Figure 6. For example, starting in 1990 (the first year for which the CPI with 2015 base is available), the 30-year difference is about 20 points: around +60% for the Consumer Price Index versus about +80% for “actual rents.” This comparison shows that one must rigorously define what is meant by “negligible effect” before claiming that different conventions would not matter. What counts as a significant difference? Indeed, even a few tenths of a percentage point each year add up to a large difference when accumulated over decades.

Moreover, the Consumer Price Index is used very broadly: for the indexation of pensions already in payment, many social benefits, the minimum wage (SMIC), but also numerous private contracts (such as alimony payments, etc.). Even a 2% difference over 30 years can represent several hundred euros each year for modest retirees — which is hardly negligible for many households.

In addition, one may question whether the evolution of “actual rents” is not underestimated by Insee. The “Loyers et Charges” survey used by Insee to measure rents is of rather poor quality, especially when compared with the resources devoted to measuring the CPI (only 4,300 dwellings surveyed, with a restricted scope — for example, furnished dwellings are excluded, even though they represent a growing share of the rental market, partly for tax reasons). Such a survey would probably be considered unacceptable if the weight of rents in the CPI were 21% instead of 6%. Indeed, the cost of this survey, €1.2 million per year, compared with the cost of calculating the CPI, around €17 million per year, is about 6%. Furthermore, there are reasons to think it leads to an underestimation of rent increases. First, because the Paris Region Rent Observatory (Observatoire des Loyers de l’Agglomération Parisienne, OLAP), for example, finds higher rent increases than the “Loyers et Charges” survey, as has been repeatedly noted in administrative reports (e.g., CGEDD (2013)). To our knowledge, this issue has still not been corrected. If the weight of rents were 21% instead of 6%, one would expect the quality of this survey (especially its sampling) to be significantly improved, the divergences with OLAP to be explained, and furnished rentals no longer to be excluded from its scope.

Finally, calculating imputed rents from actual rents raises issues in the French context, where tenant rents are tightly regulated in some metropolitan areas, and rent increases are also capped. In this context (i.e., after around 2010), one may question whether the rents in the rental market can still serve as a reference for owner-occupiers, who are not subject to the same freezes and controls.

The Case of Mortgage Holders (propriétaires accédants)

The main objection lies in Insee’s omission of imputed rents (loyers imputés), which applies to all homeowners. But for the sake of completeness, one may also mention the specific case of mortgage holders (propriétaires accédants). On this subject, the Insee Blog states the following:

For the 2 out of 10 remaining households who are mortgage holders, the “cost of housing” also takes the form of mortgage repayments, which are indeed not included in the CPI (Indice des Prix à la Consommation, IPC). However,

- the share of these repayments corresponding to interest is directly deducted from their income, and therefore is included in the measurement of purchasing power (for a standard 20-year mortgage at a 2% rate, this represents about 1/6 of monthly payments over the whole duration of the loan, nearly double in the early years);

- in the end, only the repayment of the principal is excluded from the measurement of purchasing power, on the grounds that it is an investment expenditure corresponding to the accumulation of real estate wealth (and symmetrically, the proceeds from the sale of real estate are not counted as additional income in the measurement of purchasing power).

This excerpt from the Blog unfortunately creates more confusion than clarity, although it is admittedly not an easy topic. First, the distinction made by the Blog between the share of repayments corresponding to interest and that corresponding to principal has little meaning. According to this accounting convention, only interest payments reduce income, while principal repayments are considered the accumulation of housing wealth. This is incorrect for several reasons. First, because the “true” cost of borrowing is closer to a real interest rate (nominal interest rate minus inflation) than to a nominal rate. When inflation is higher, nominal rates are also higher (as in the 1980s), which increases nominal interest payments, even though the real cost of borrowing is lower. Moreover, the level of interest payments depends on the down payment and the outstanding principal, whereas the consumption of housing corresponds to imputed rents regardless of the amount of the loan still outstanding (in reality, closer to the real interest rate multiplied by the total value of the apartment or house).

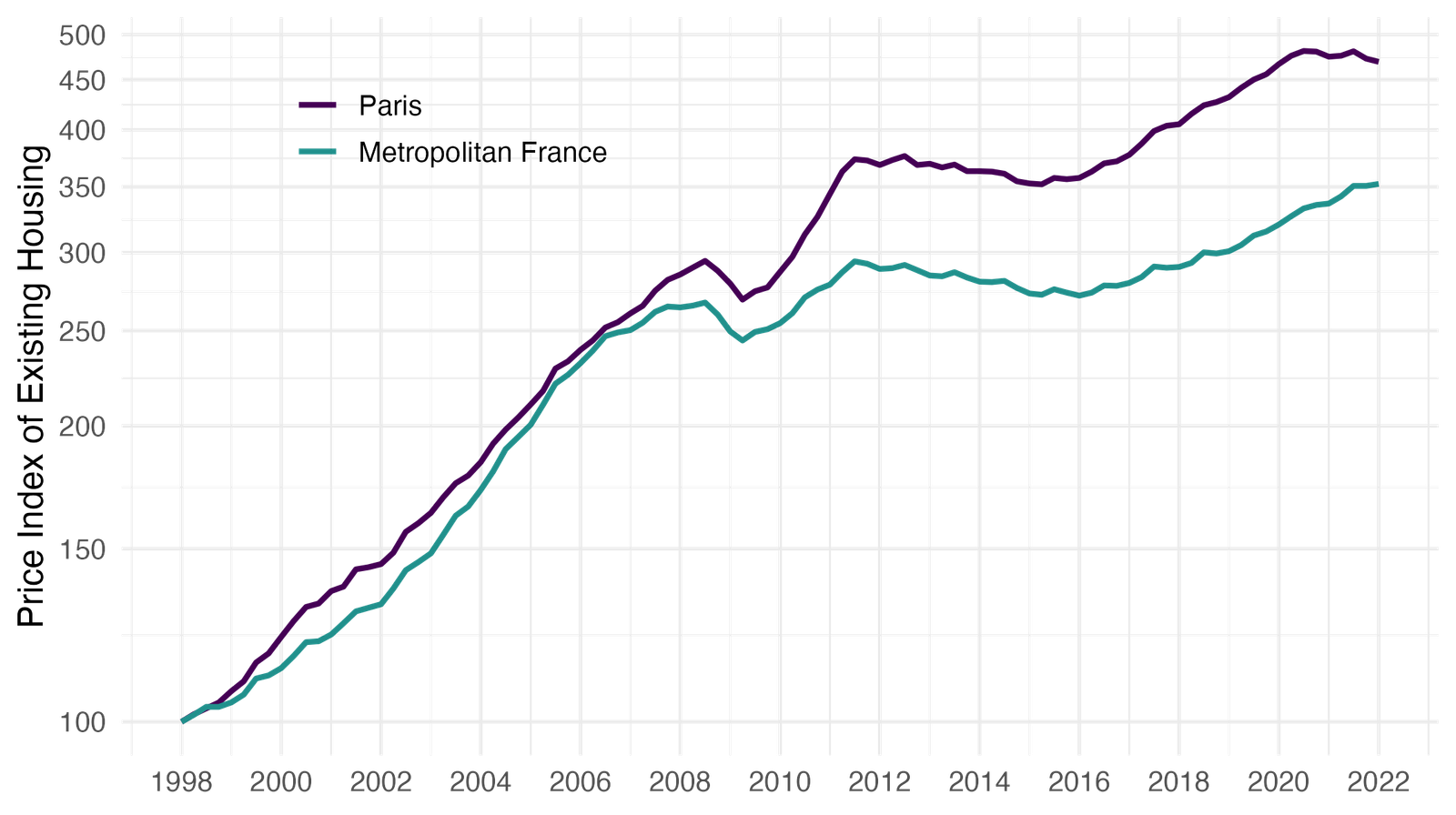

That said, it is true that not all mortgage repayments correspond to housing consumption, and in economic theory, part of these repayments is generally seen as savings accumulation (this is probably what the Blog refers to with the term “investment expenditure,” even though there is no investment strictly speaking). In this sense, it is not legitimate to include the full amount of mortgage repayments in the CPI, but only the share corresponding to imputed rents — which is not currently done. End of story? No, it is not that simple. Indeed, the reasoning below implicitly assumes that no one is forced to buy rather than rent, and that the act of buying always amounts to a joint decision to consume a given quantity of imputed rents (housing services) and to save at a certain level. In practice, however, most people do not perceive homeownership this way, which creates a disconnect between the economic/statistical interpretation and the lived experience of the majority of the population. For instance, many homebuyers do not think of the fact that buying implies accumulating more savings the higher housing prices are. Conversely, they view the inability to buy as downward mobility, and homeownership as a consumption good. And partly for good reasons: homeowners enjoy rights that tenants do not, meaning that renting and owning are not perfect substitutes in terms of consuming housing services. One consequence of this is that as housing prices rise, the effort rate (taux d’effort) and thus savings rise as well, since first-time buyers (primo-accédants) keep purchasing rather than renting, even when prices climb. For the economist, there is a paradox in this behavior: why should falling interest rates, which increase the present value of future rents, lead to a rise in household savings exactly equal to the increase in housing prices they generate? As one can see, for the first-time buyer, the amount of savings involved in purchasing is not a choice variable. In this context, excluding house price dynamics from the CPI can appear arbitrary. The difficulty is that including purchase prices in the CPI would potentially have a major effect on the index for first-time buyers: since 1998, the purchase price of existing homes has risen by about +250% in France, and by +375% in Paris — see Figure 7. By contrast, net sellers of housing have seen their living standards rise by the same amount that first-time buyers’ standards of living have declined.

Finally, Insee has recently published many studies showing that falling nominal interest rates and longer loan maturities have helped sustain home affordability, even as house prices soared. Yet, much of this reasoning again rests on an error. It is true that lower real interest rates do reduce the cost of borrowing for buyers. However, the part of the decline in nominal rates that comes from lower inflation does not reduce the cost of borrowing (a fall in inflation simply implies a smaller reduction in the effort rate over the life of the loan). Likewise, lengthening loan maturities also entails a loss of purchasing power, insofar as it keeps initial monthly payments stable in a context of rising house prices, but at the same time it extends the period during which disposable income is burdened by debt repayments.

Bibliography

Footnotes

Following a discussion on February 3, 2022, on Twitter that questioned my “good faith” (tweet), I try here, if not to convince my interlocutor on the substance, at least to persuade him of my “good faith.” Having worked on this issue of housing inclusion in the Price Index for a long time (Geerolf (2018)), I feel legitimate in challenging the statements made in this Blog.↩︎

In fact, this debate is much older, and neither Emmanuel Todd nor Philippe Herlin (2018) were the first to raise it. On October 23, 2007, Christine Lagarde, then Minister of the Economy, set up a commission on the measurement of purchasing power, chaired by Alain Quinet, which resulted in a report that already mentioned this issue (Quinet (2008)). This report also drew on the report no. 73 of the Conseil d’Analyse Économique, cited in Philippe Herlin’s book (Moati and Rochefort (2008)).↩︎

Only the purchase of new housing corresponds to investment in the economic sense. This amounted to €58.4 billion in 2020, a sum smaller than both implicit and actual rents (and this was already true before 2020, before Covid-19). By contrast, the purchase of an existing dwelling is not “investment” in the proper sense, even if the word is used loosely in everyday language: “investment” does not have the same meaning in macroeconomics (and national accounting), where it signifies an increase in the capital stock, as it does in common usage. The purchase of an existing dwelling is not investment expenditure, nor consumption expenditure for that matter, just as the purchase of an LVMH share on the secondary market has no counterpart in the national accounts. The Blog author here seems to confuse “flows” and “stocks.” By contrast, the ownership of an existing dwelling does imply a consumption of housing services, either by the tenant or by the owner-occupier.↩︎

“Finally, it should be noted that the deliberate exclusion of certain types of goods and services by political decision, on the grounds that the households to whom the index is intended should not buy these goods or services, or should not be compensated for the price increases of these goods and services, cannot be recommended because it exposes the index to political manipulation. For example, suppose it is decided that certain products such as tobacco or alcoholic beverages should be excluded from a CPI. It is possible that, when taxes on products are increased, these products are deliberately selected for higher taxes in the knowledge that the resulting price increases would not be reflected in the CPI. Such practices are not unknown.” The price of tobacco has indeed risen sharply in France since 1993, without leading to a parallel revaluation of minimum social benefits and pensions — a form of partial de-indexation.↩︎

Was the title of the Blog originally that of the link https://blog.insee.fr/mais-si-linsee-prend-bien-en-compte-le-logement-dans-linflation-et-au-bon-niveau/ “Mais si, l’Insee prend bien en compte le logement dans l’inflation et au bon niveau”? - “Insee takes into account housing in the CPI at the correct level”.↩︎