Main result

Perhaps one of my favorite subjects.

I have thought for a long time that there are too much savings in the world. My Ph.D. thesis was titled “Bubbles and Asset Supply”.

There’s a saying in French that says “only fools don’t change their mind”, and yet I have not changed my mind since 2013.

Since then, interest rates have gone even lower, and asset prices have reached even higher levels.

We’ll see that Keynes actually contemplated these ideas in Book VI where he talks about the potential vanishing importance of thrift.

“euthanasia of the rentier”: Keynes fantasized about a world of permanently low interest rates. In the final chapter of “The General Theory” he imagined an economy in which abundant available capital causes investors’ bargaining power, and hence rates, to collapse.

The idea that there is enough saving in the world given investment demand. I see this as an alternative to the Phillips curve to determine the (AS) curve. Once again, remember Summers (1991)’s provocative paper on “Should Keynesian Economics Dispense with the Phillips Curve?”

Something Keynes missed: rational bubbles to prevent the “euthanasia of the rentier”.

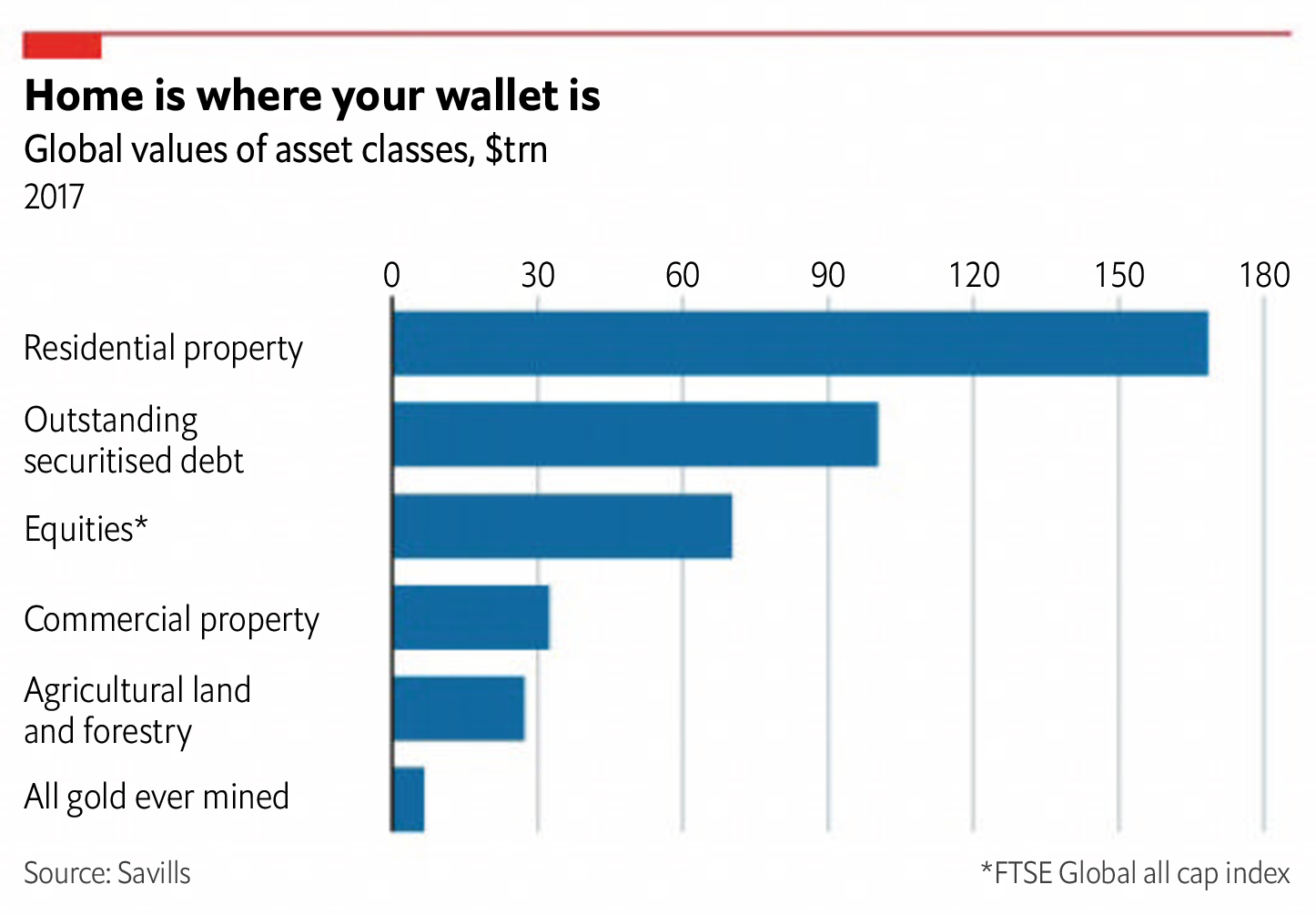

If one wants to transfer resources into the future, how can one do this? Here’s the list:

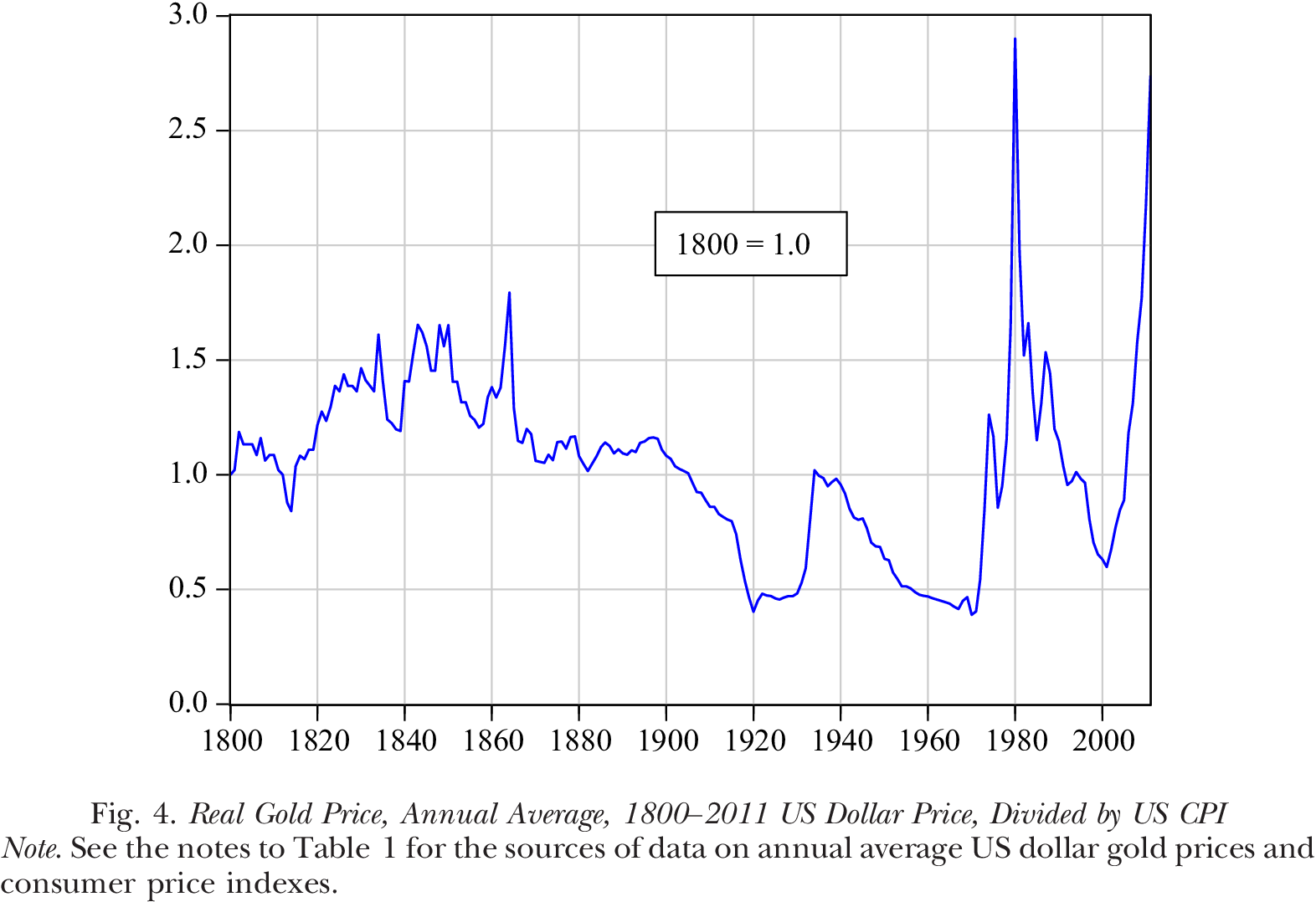

Gold.

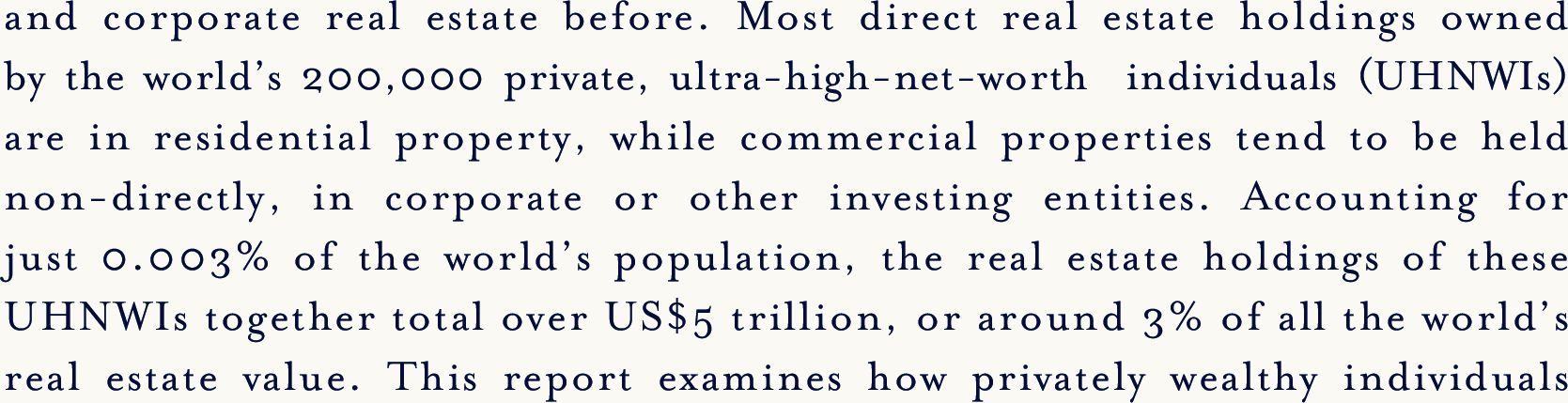

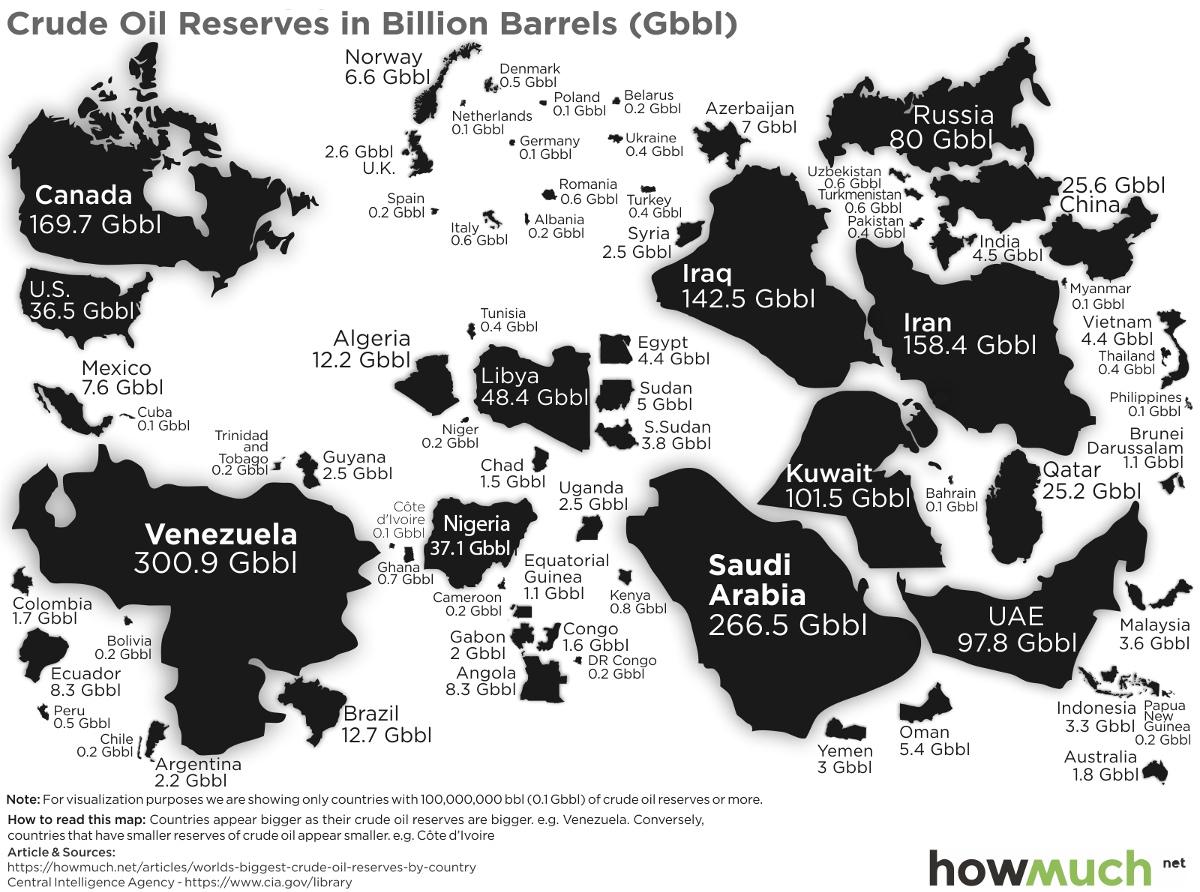

Oil.

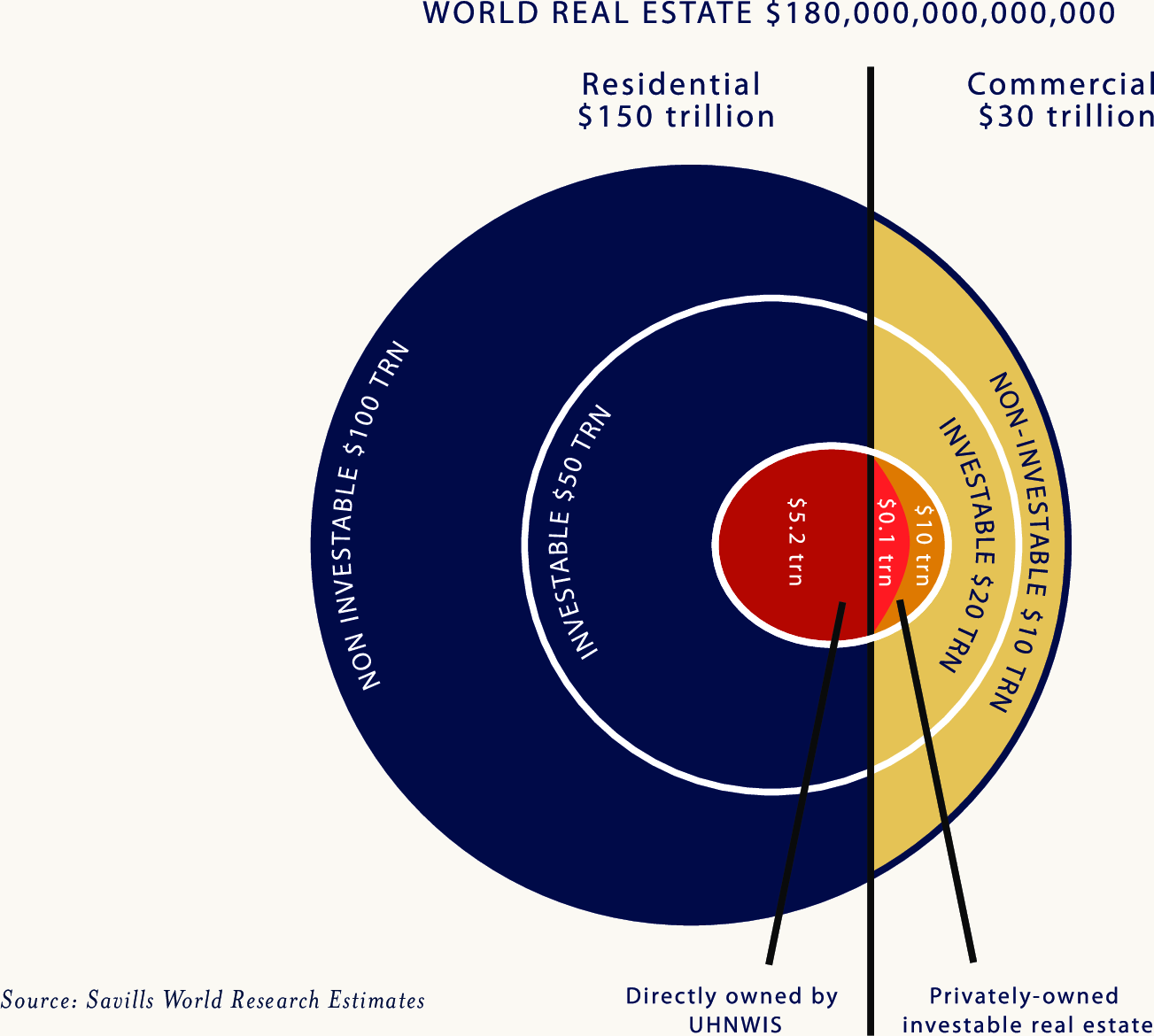

Residential property.

1.73 trillion barrels in soil.

World uses 95 million barrels per day = 34 billion barrels per year.

Enough to last another 50 years.

Say value is $65/Barrel: \[\boxed{\text{Proven Oil Reserves} = 112 \text{ Tn Dollars}}\].

1 metric ton = 1,000 kg = 1,000,000 grams.

1 Gram = $50.

1 Metric ton = $50 Million

U.S. = 8000 Metric Ton = $400 Bn. (2% of GDP)

Harrod, R. F. “An Essay in Dynamic Theory.” The Economic Journal 49, no. 193 (1939): 14–33. html / pdf

Nowadays, following Solow (1956), we usually assume that it is.

And yet, we see that there often exists a paradox of thrift.

Blume and Sargent (2015) do not like this paper at all !

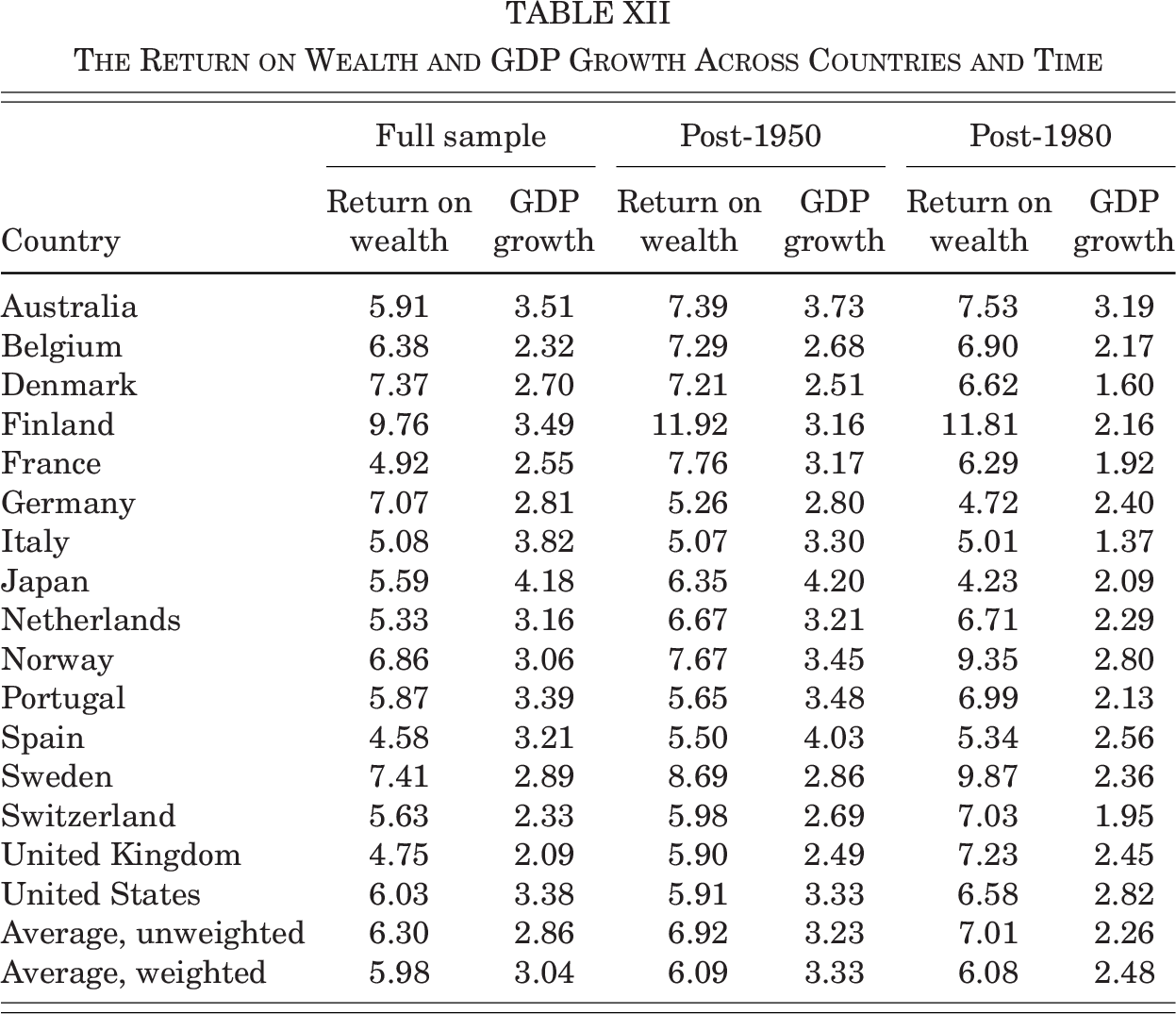

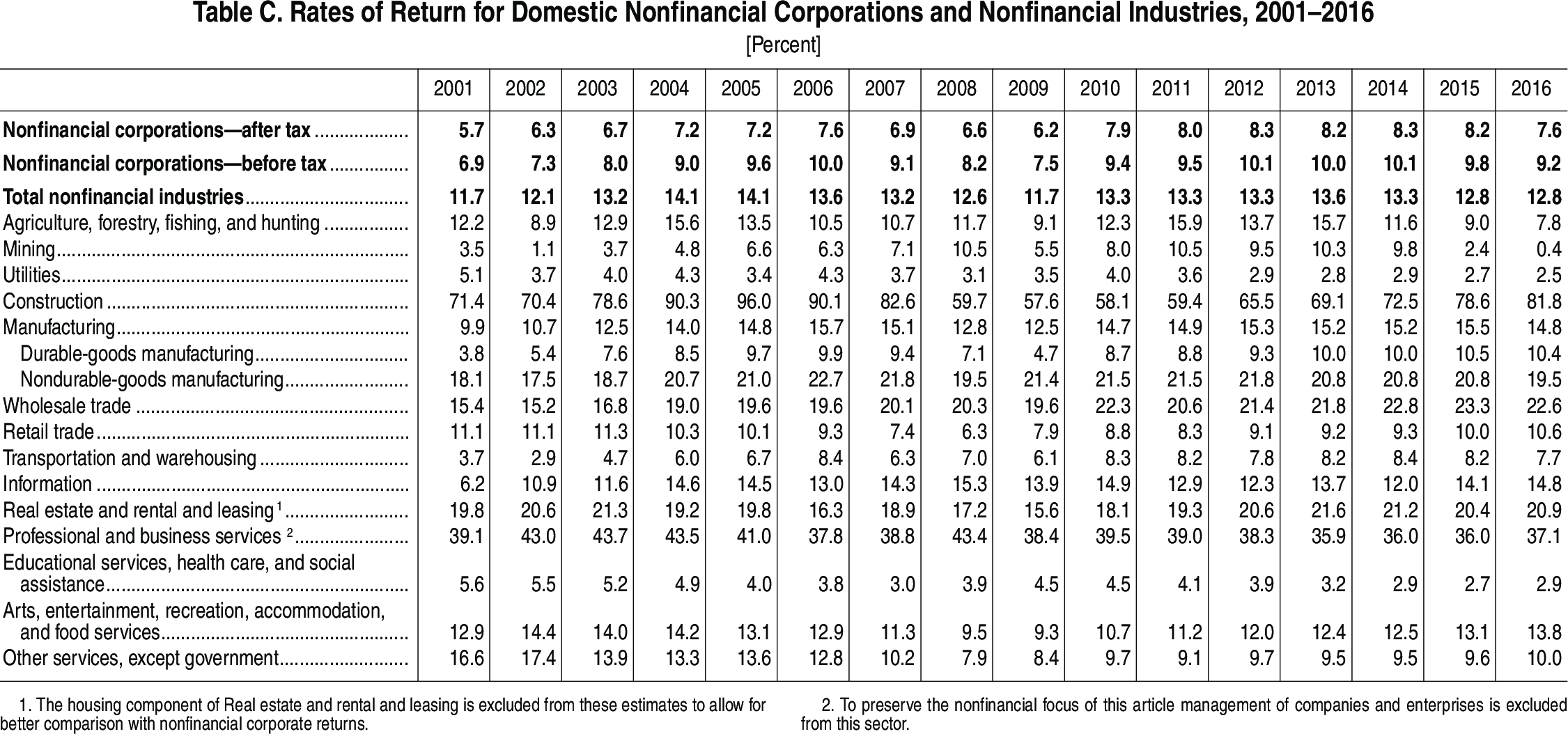

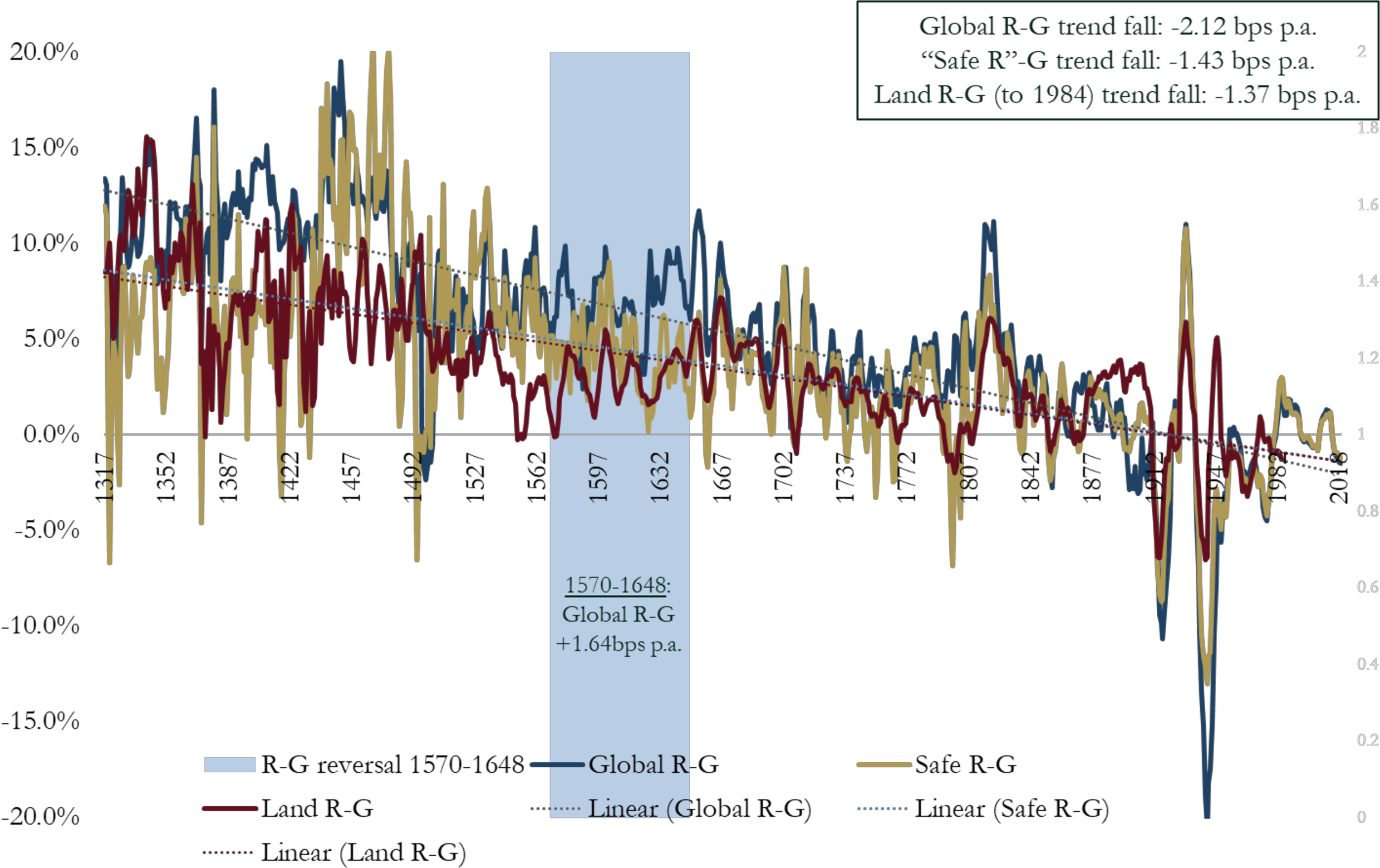

Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century forcefully argues that the returns to capital are very high.

And that capital can be forever accumulated.

Piketty, Thomas, and Gabriel Zucman. “Capital Is Back: Wealth-Income Ratios in Rich Countries 1700–2010.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129, no. 3 (August 1, 2014): 1255–1310. pdf / html

Piketty, Zucman (2014) argue that “capital is back”.

However, capital is back not because the accumulation of net investment rates (gross investment rates net of depreciation) but rather because the price of existing capital (stocks, equities) increases.

This makes a very big difference.

\(K/Y\) rises not because of the accumulation equation: \[K_{t+1} = K_t + \underbrace{(I_t - \delta K_t)}_{\text{Net Investment}}\]

Much of Piketty’s book Capital relies on work with Gabriel Zucman, particularly the 2014 QJE piece.

As we just saw, there are conceptual issues with the view that “Capital is Back”, and therefore with the whole premise of the book.

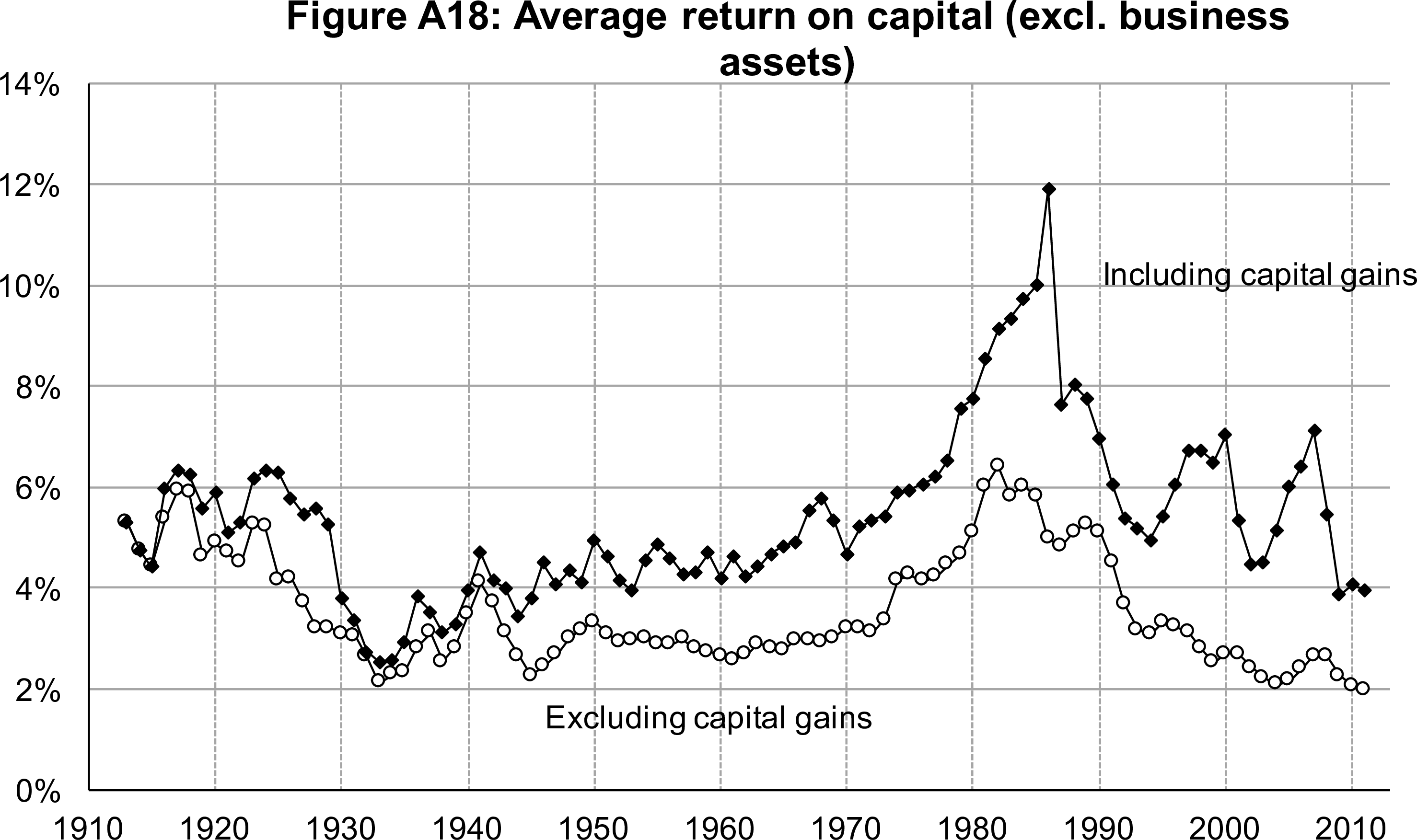

Where Thomas Piketty is correct, is that the return on wealth is indeed very high, and has perhaps even gone up over time.

However, the theory on which Piketty relies is super-neoclassical, that is, even more “optimistic” about the growth process than Solow. In mathematical terms, neoclassical economists usually assume a very large elasticity (\(\sigma=1\)), one that is likely too large. Piketty’s assumption is that the elasticity is even larger.

Piketty’s assumptions are indeed super-neoclassical (perhaps ironically?):

Neoclassical: \(\sigma=1\) (Kaldor facts: \(K/Y\) is constant)

Keynesian: \(\sigma<<1\), capital satiation even.

Super-neoclassical: \(\sigma>1\): rising \(K/Y\) ratio.

Is the capital/ income ratio very flexible in the long run, as Piketty (2014) says?

Or is it the contrary?

This would then explain the paradox of thrift.

We may have a long-run paradox of thrift.

Contrast between:

Keynesian assumptions: “elasticity pessimism”. Most adjustments take place through quantities. Prices play very little role.

Neoclassical assumptions: “elasticity optimism”.

The elasticity of substitution is very important to know what the welfare effects of capital taxation are.

Piketty proposes high capital taxation, which in the general equilibrium of a model which has \(\sigma>1\) decreases capital accumulation, and hence welfare, by a lot.

\(r\), the real rate of return to capital, seems to be roughly constant. (why that is, is left unspecified)

\(w\), the real wage, on the other hand, grows at the rate of productivity growth.

Thus, this seems to justify that there is a lot of substitutability in production: when the \(w/r\) ratio rises at the rate of productivity growth, it appears as if simultaneously the capital stock per person \(K/L\) also rises at the rate of productivity growth \(A\), so that \(K/(AL)\) stays constant.

This “balanced growth” is usually what justifies neoclassical assumptions.

An alternative explanation, of course, is that productivity growth is Harrod-neutral.

I think that we can see that there isn’t much capital / labor substitution intuitively.

First, machines are perhaps somewhat substitutable with labor, but it’s really hard to see why structures and real estate would be.

In fact, real estate is more a durable good than something which is useful in production:

So clearly, the fact that it rises together with GDP, in an approximately constant fashion cannot be coming from capital labor substitution.

Instead, this likely comes from the consumption side: as people get richer, they tend to consume a larger quantity of housing (which would happen with homothetic preferences).

But then, should we not worry about that issue more generally?

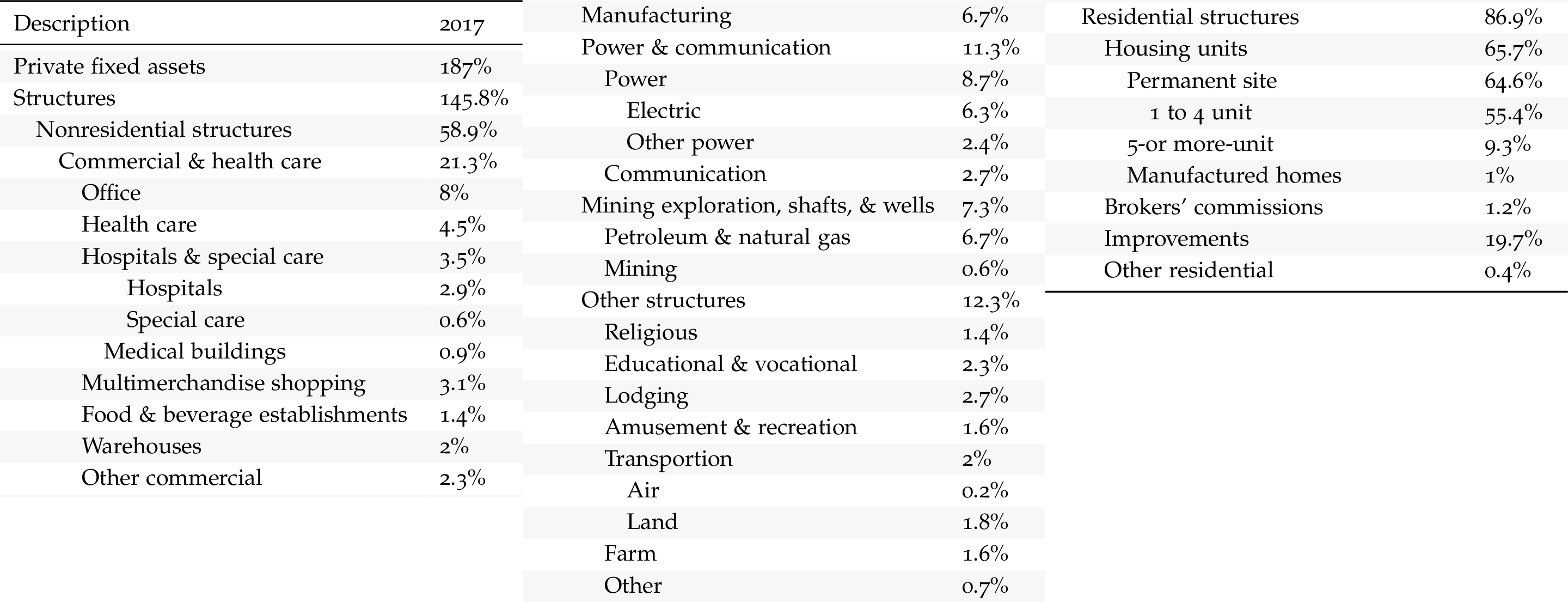

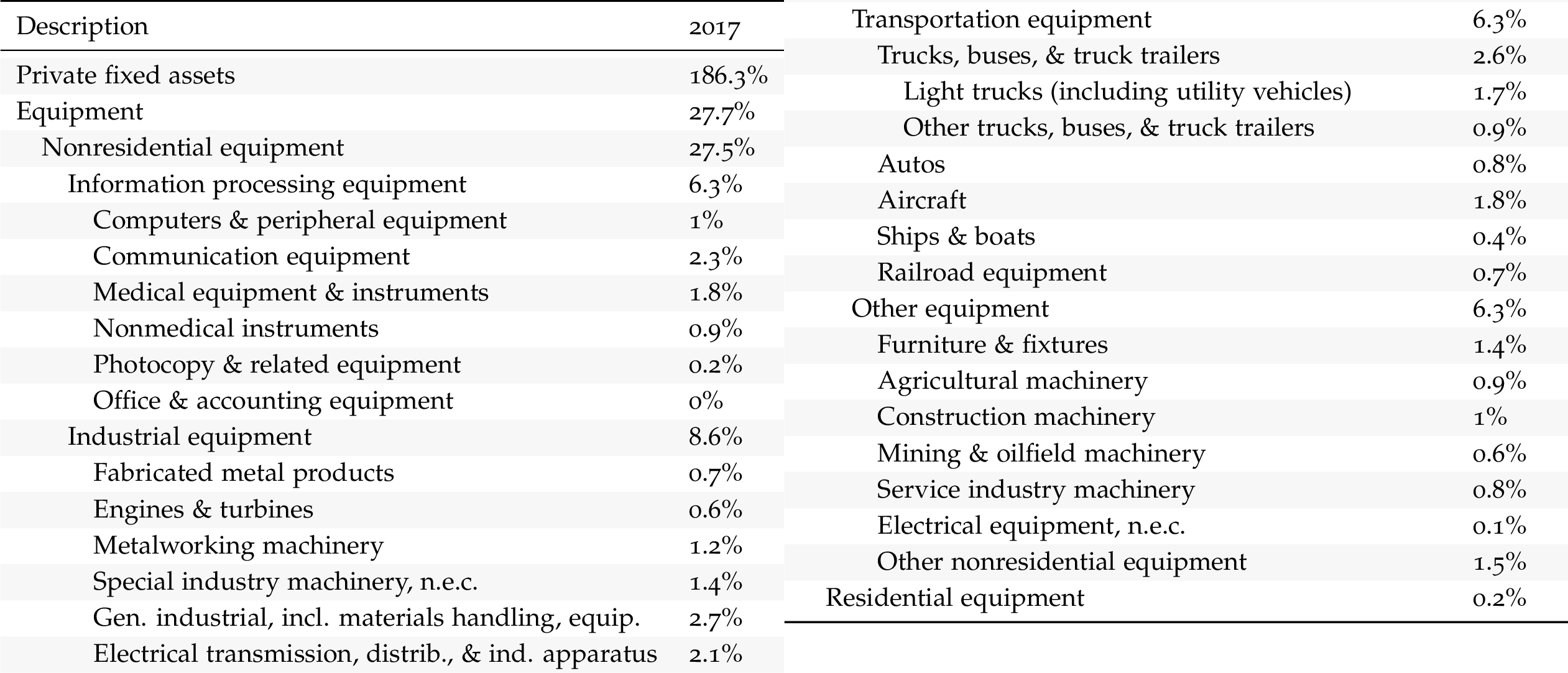

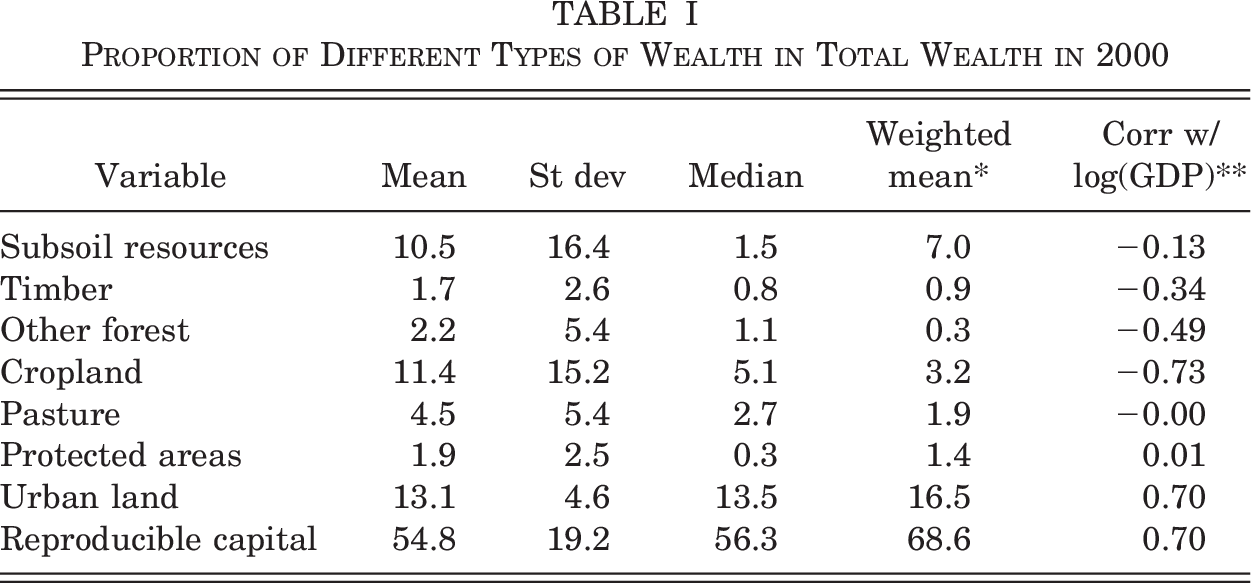

What is capital, in practice?

In the U.S., the answer is it’s mostly structures.

Very far from Solow’s capital stock.

Equipment, the substitutable part of capital, is actually really small.

In 2017, book capital was only 186.3% of GDP in total.

Equipment was 27.7% of GDP, of which:

6.3% of GDP was transportation equipment (so again, mostly infrastructure, not something that firms can substitute with labor)

6.3% of GDP was information processing equipment

8.6% of GDP was industrial equipment.

6.3% of GDP was industrial equipment.

To conclude, at most 14.9% of GDP, or < 8% of the 186.3% of GDP was potentially substitutable with labor.

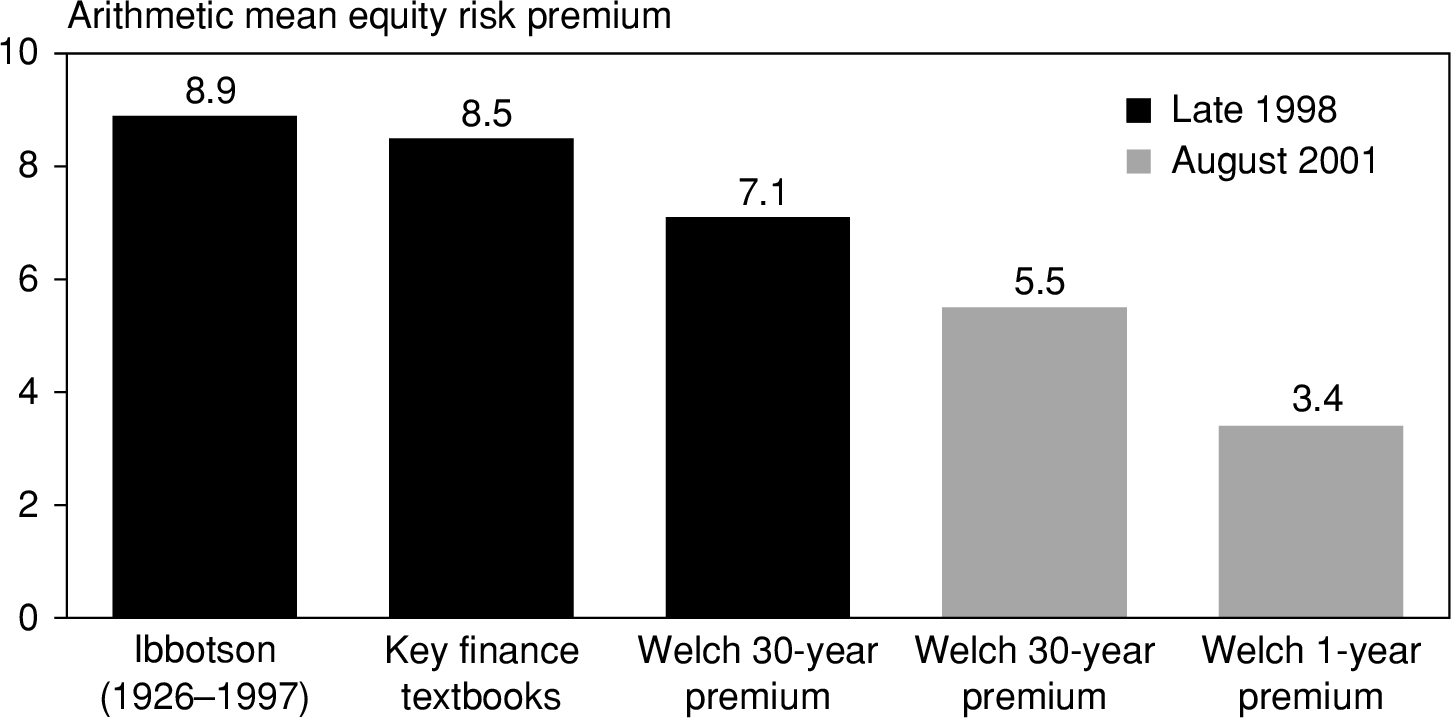

In November 2013 Larry Summers, at the IMF Fourteenth Annual Research Conference in Honor of Stanley Fischer, argued in favor of “secular stagnation”, or the idea of an excess of savings over investment.

I agree with Larry Summers’ secular stagnation view.

Saez, E., & Zucman, G. (2016). Wealth Inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(2), 519–578. html / pdf

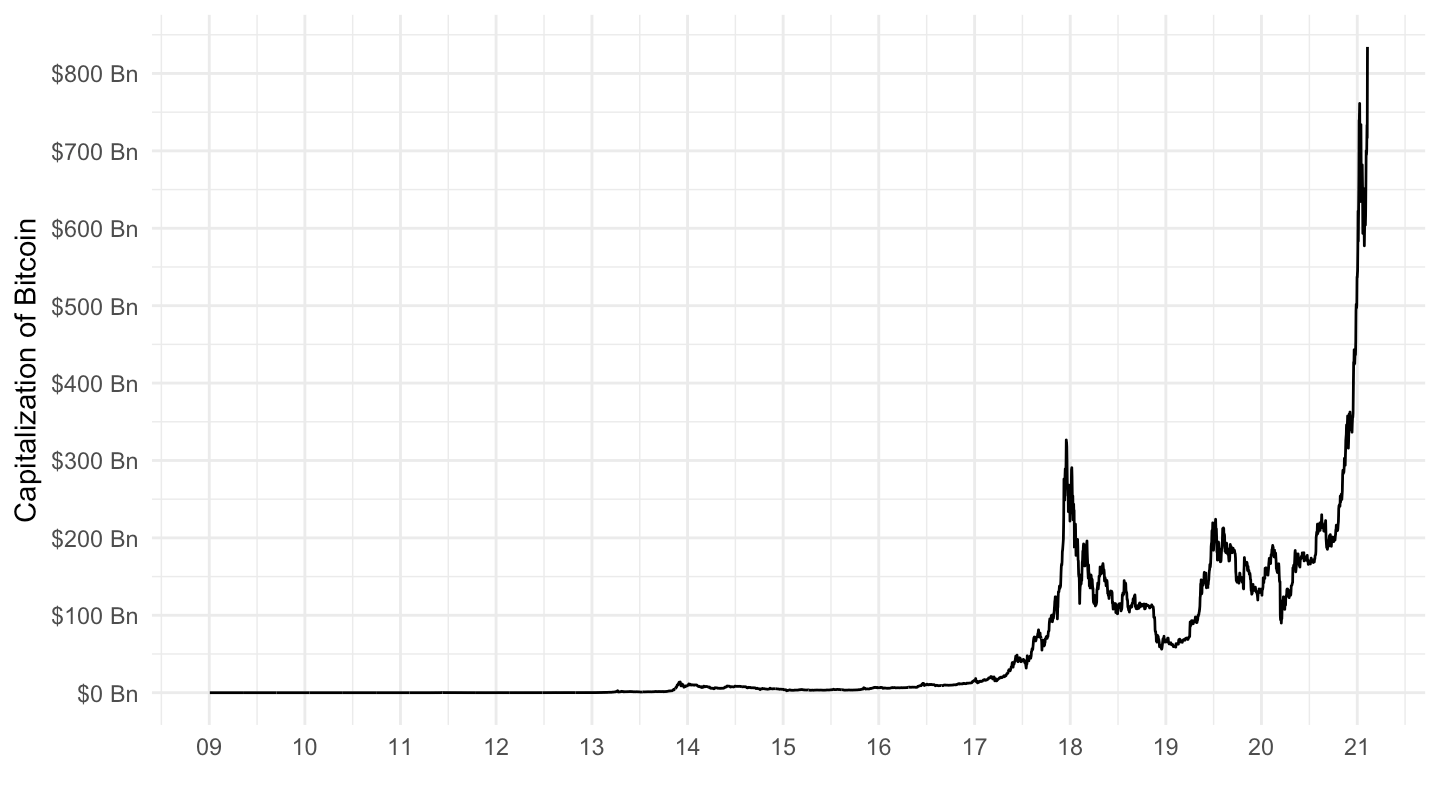

With too much capital, existing capital starts to be overvalued.

As a consequence, there are rational bubbles.

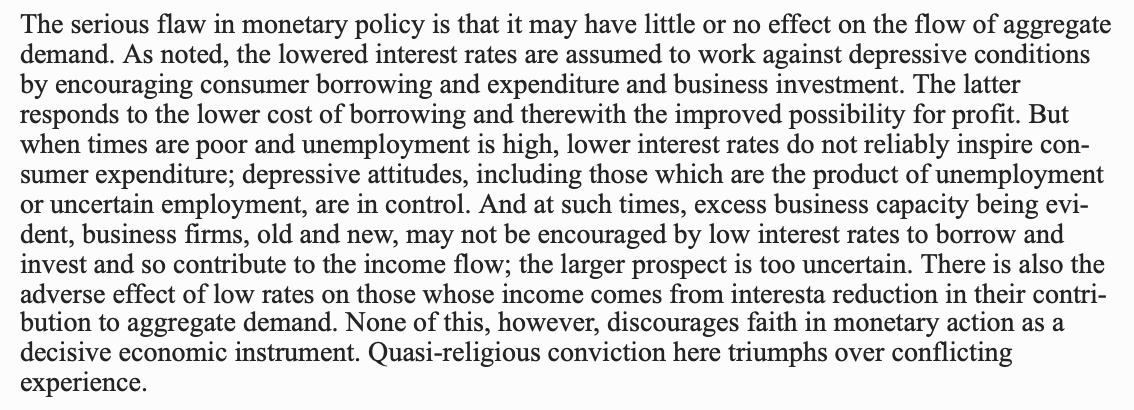

There is a view that “aggregate demand” is important because of “sticky prices”.

Based on a “Phillips Curve” view of the world. Paul Samuelson in the 3rd edition of his Economics textbook: > In recent years 90% of American economists have stopped being ‘Keynesian economists’ or ‘anti-Keynesian economists’. Instead they have worked towards a synthesis of whatever is valuable in older economics and in modern theories of income determination. The result might be called neo-classical synthesis and is accepted in its broad outlines by all but about 5 per cent of extreme left wing and right wing writers.

I do not believe in the neoclassical synthesis: KEynesian short-run, Neoclassical long-run. I don’t think there is any empirical basis for this dichotomy.

I’m not sure that aggregate demand effects have anything to do with sticky prices.

Monetary policy has effects. Does this imply sticky prices?

I don’t think so!

The typical argument goes as follows: “As a consequence of price stickiness, changes in aggregate demand, typified by an increase in the money stock, affect the quantity of output and employment in the short run.”

In the long run, purely nominal changes do not have real effects.

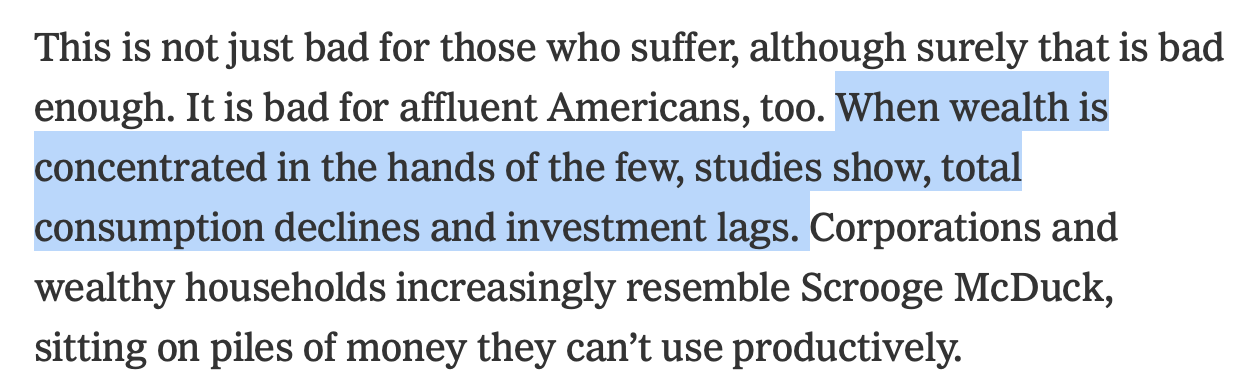

Galbraith, in The Good Society:

Bernanke, thinking on the secular stagnation hypothesis:

With a growing economy, the condition for dynamic inefficiency is \(r<g\). \(r\) need not be negative.

At that rate, it’s really not clear “it would pay to level the Rocky Mountains to save even the small amount of fuel expended by trains and cars that currently must climb steep grades”.

For that to be profitable, you would need the corresponding gain in fuel to be growing with \(g\), the rate of growth of the economy.

Discussion on land, and whether there exist enough long lived assets to store value.

In fact, to the extent that people want to own their homes, a fall in the interest rate may paradoxically lead to an increase in saving (note that the income effect would push in the same direction), which amplifies worries of secular stagnation.

Think of it really as “real-keynesian” economics. What about the very convincing evidence in Romer and Romer (2004) that monetary shocks have real effects. Once again, you should really think of shocks to the cost of housing as shocks to the nominal interest rate.

Macroeconomics became a distinct field in the 1930s as a byproduct of inquiries by John Maynard Keynes and some contemporaries into the causes of, and cures for, mass unemployment and great contractions.

Very old debate between Malthus and Ricardo

Fiona Maclachlan, “J.A. Hobson and the Economists,” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 25, no. 2 (2002): 297–308.

F. C. Maclachlan, “The Ricardo-Malthus Debate on Underconsumption: A Case Study in Economic Conversation,” History of Political Economy 31, no. 3 (1999): 563–574, https://doi.org/10.1215/00182702-31-3-563.

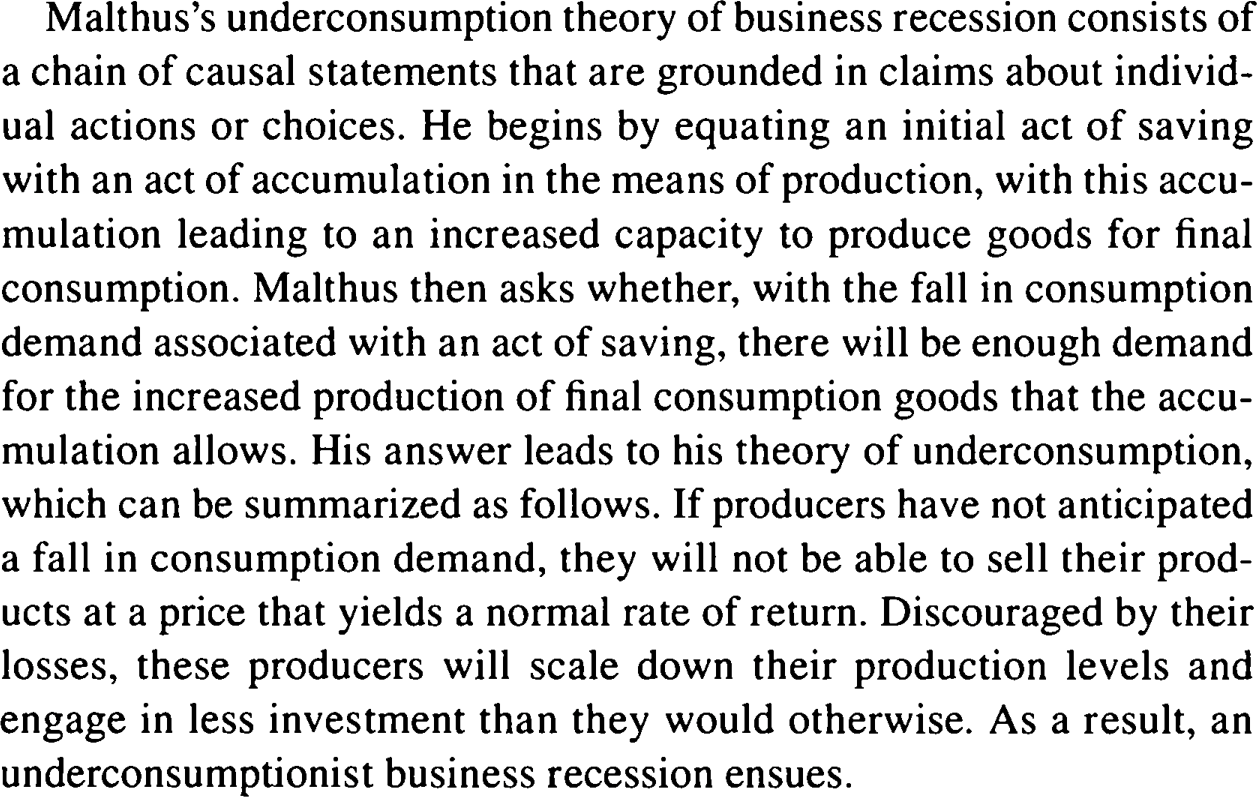

The essence of Malthus’s position is his objection to the supposed generality of Adam Smith’s proposition that “every prodigal appears to be a public enemy, and every frugal man a public benefactor.”

Malthus’s point is not that saving is always harmful, but that it cannot be thought to be always beneficial.

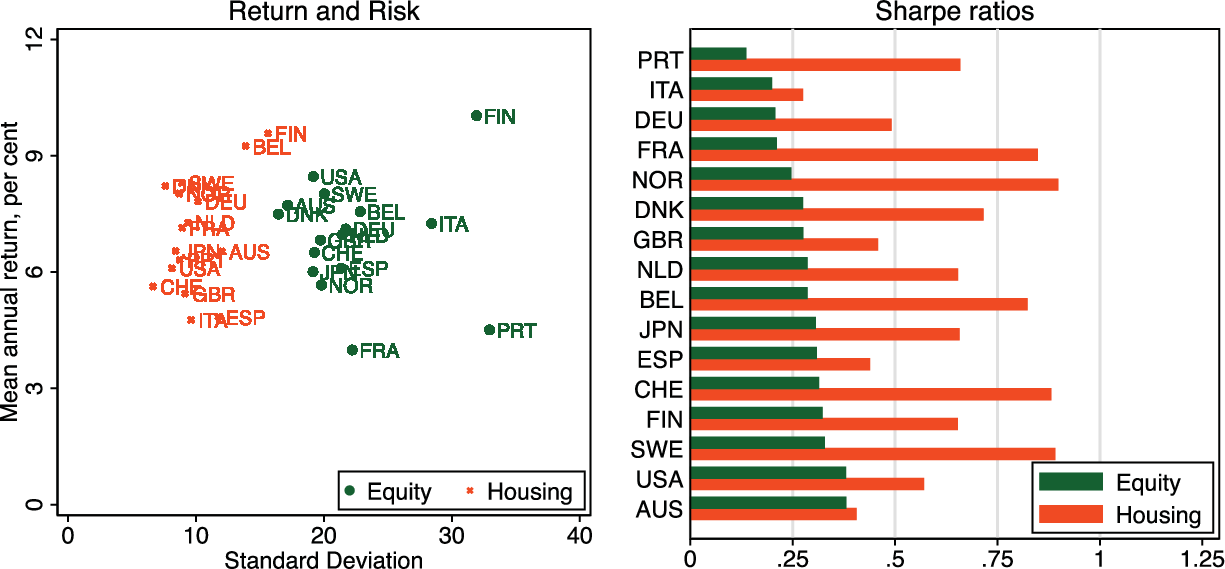

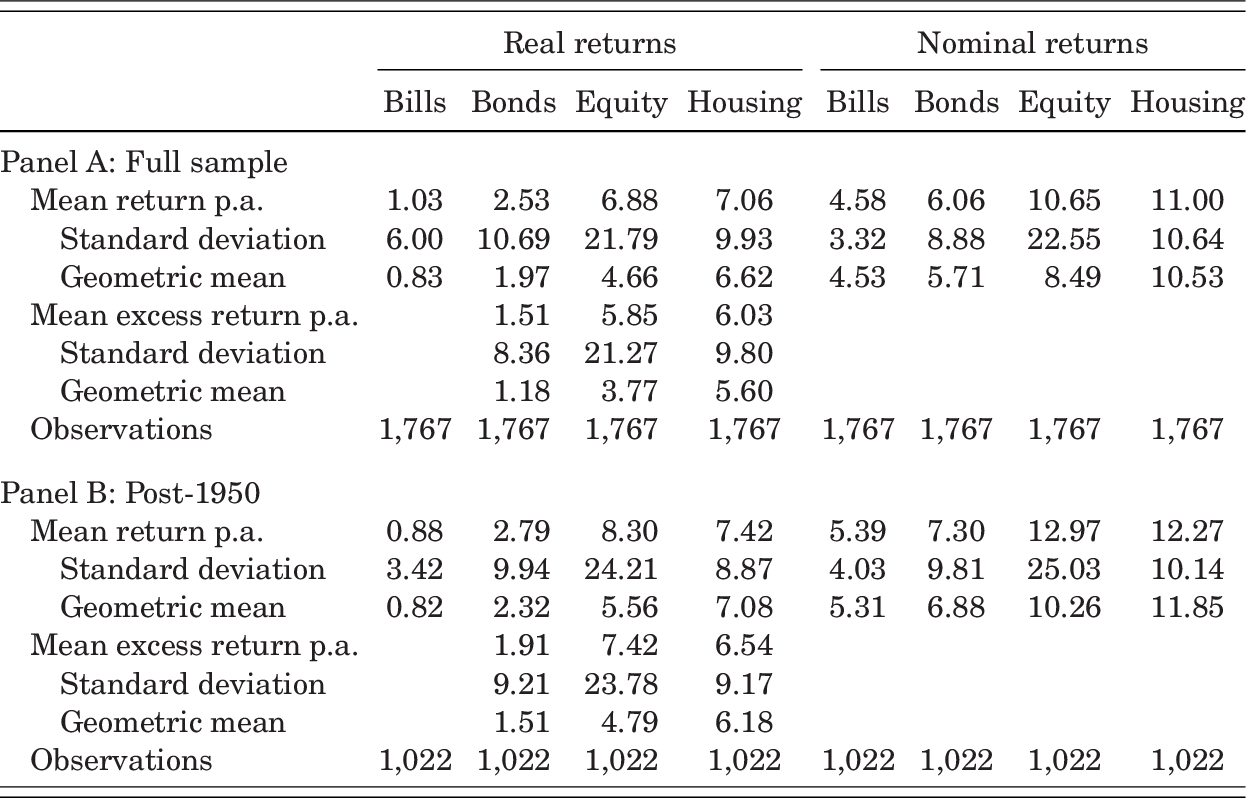

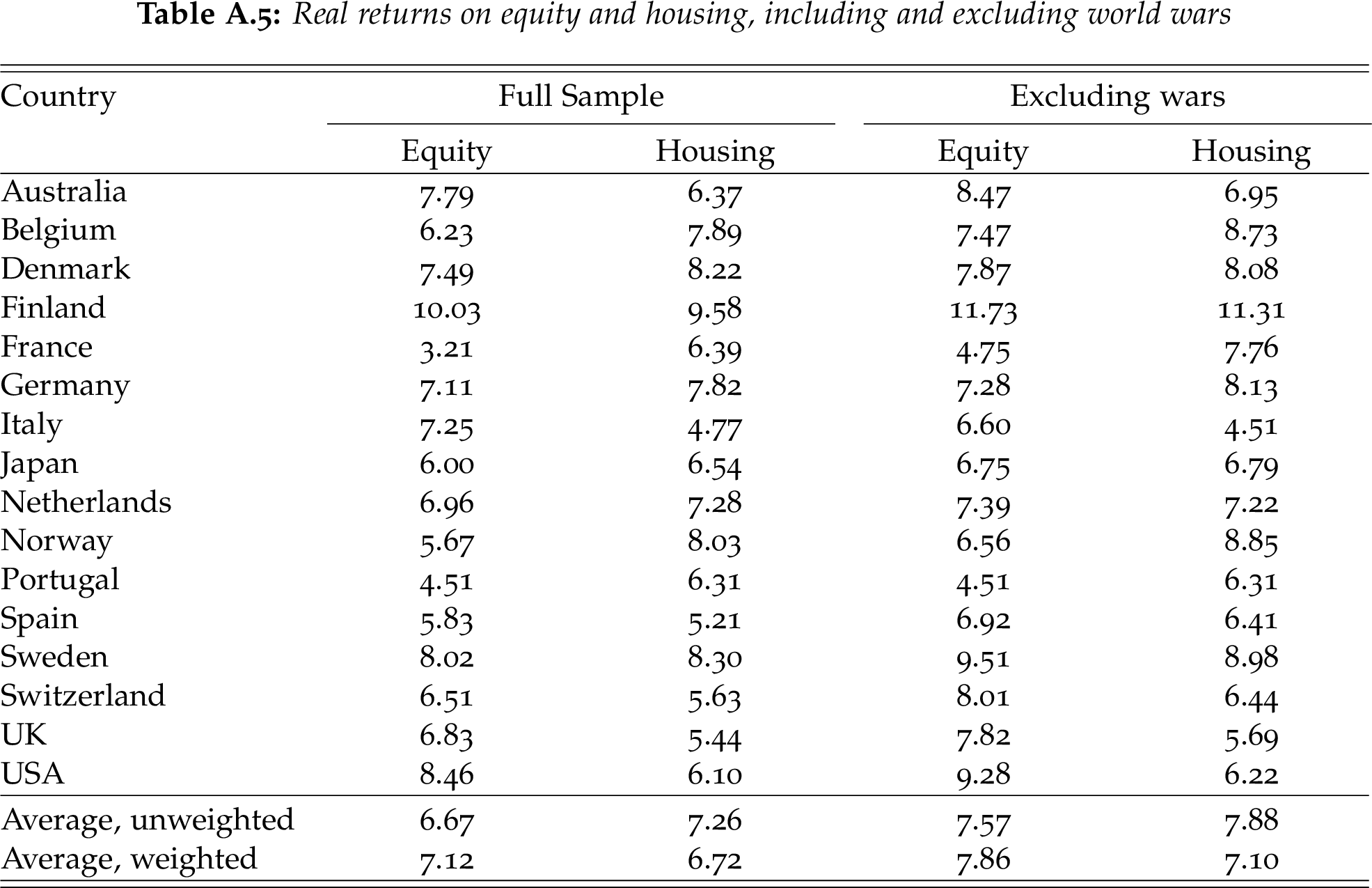

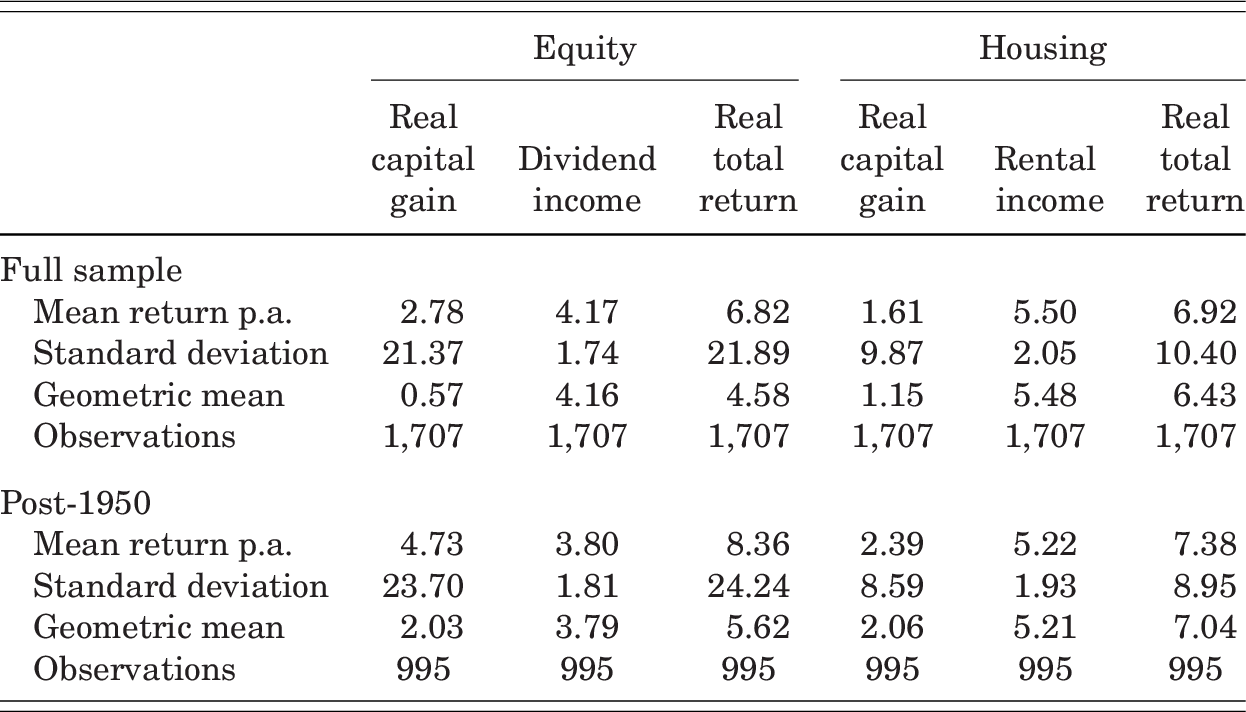

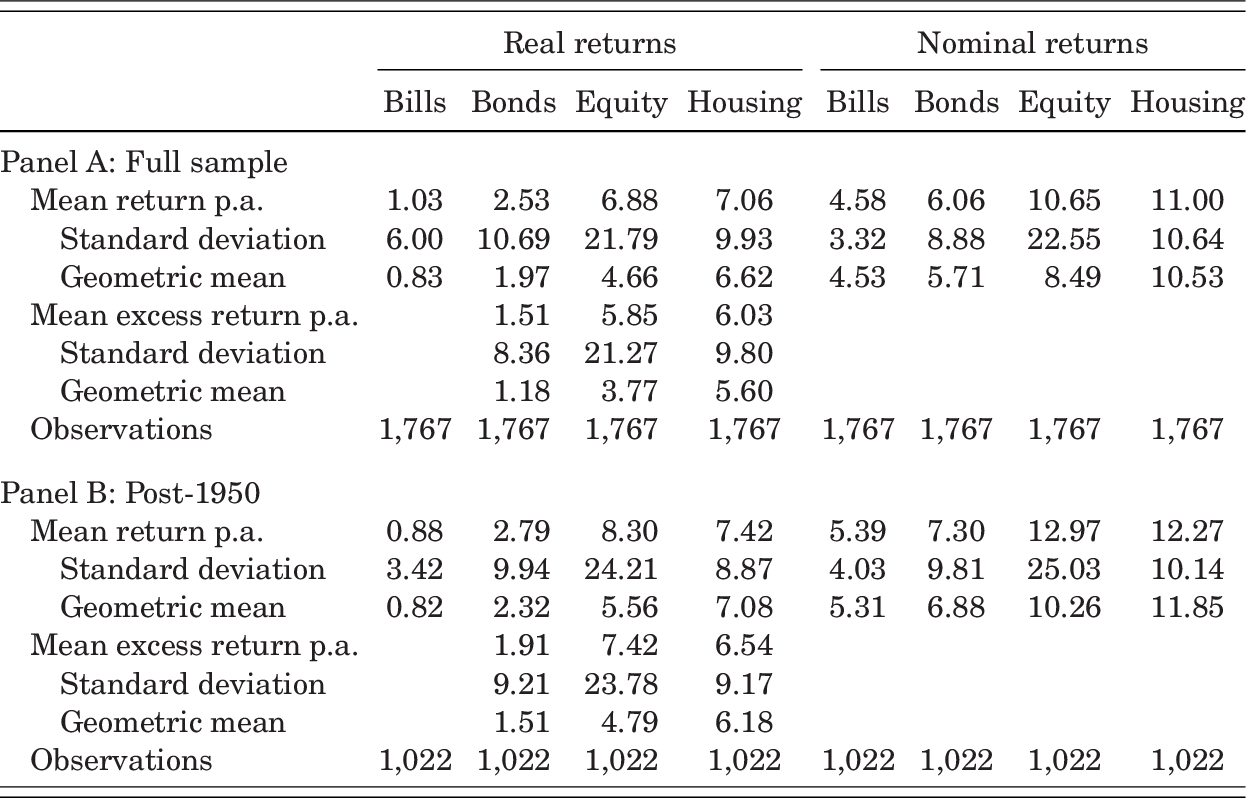

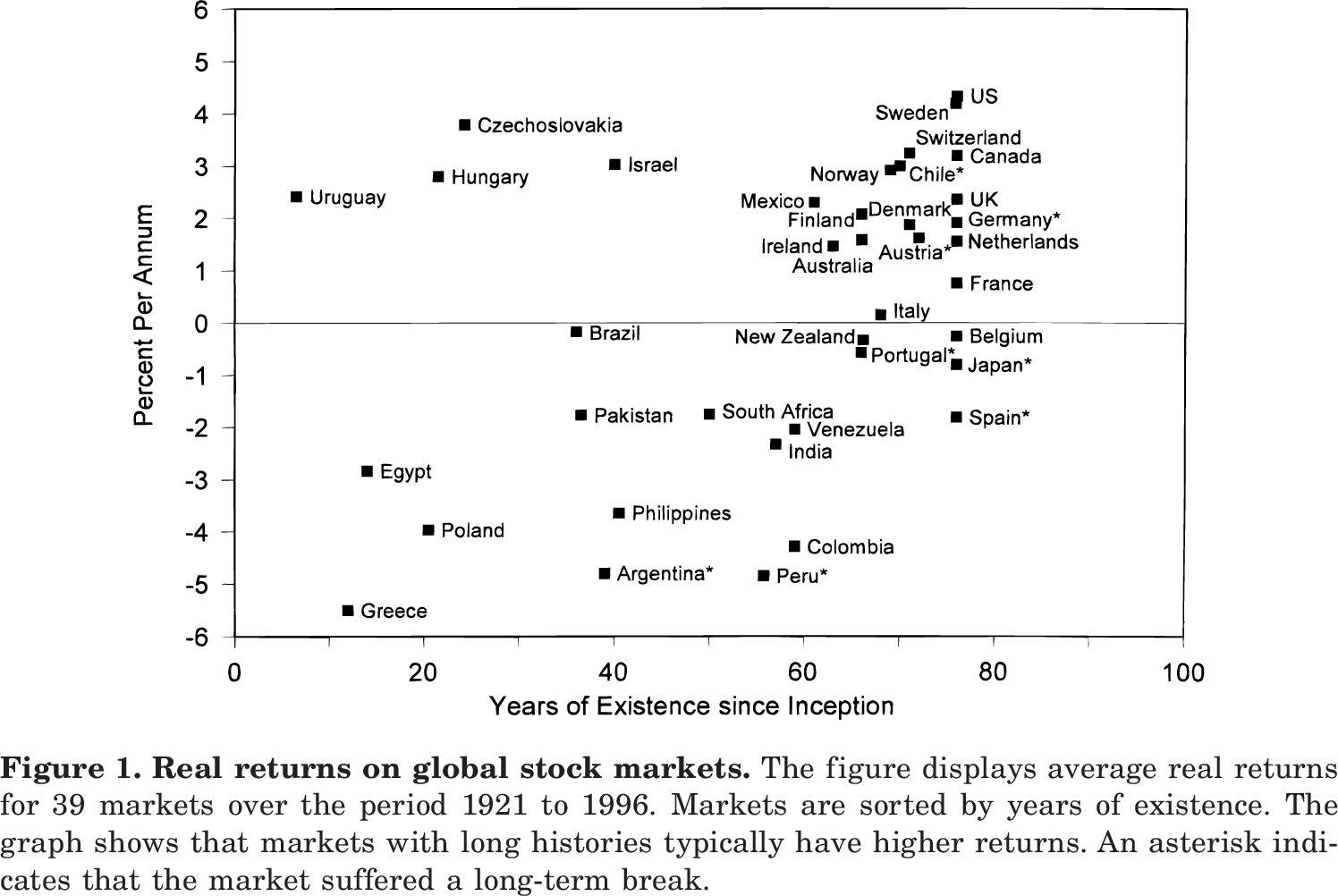

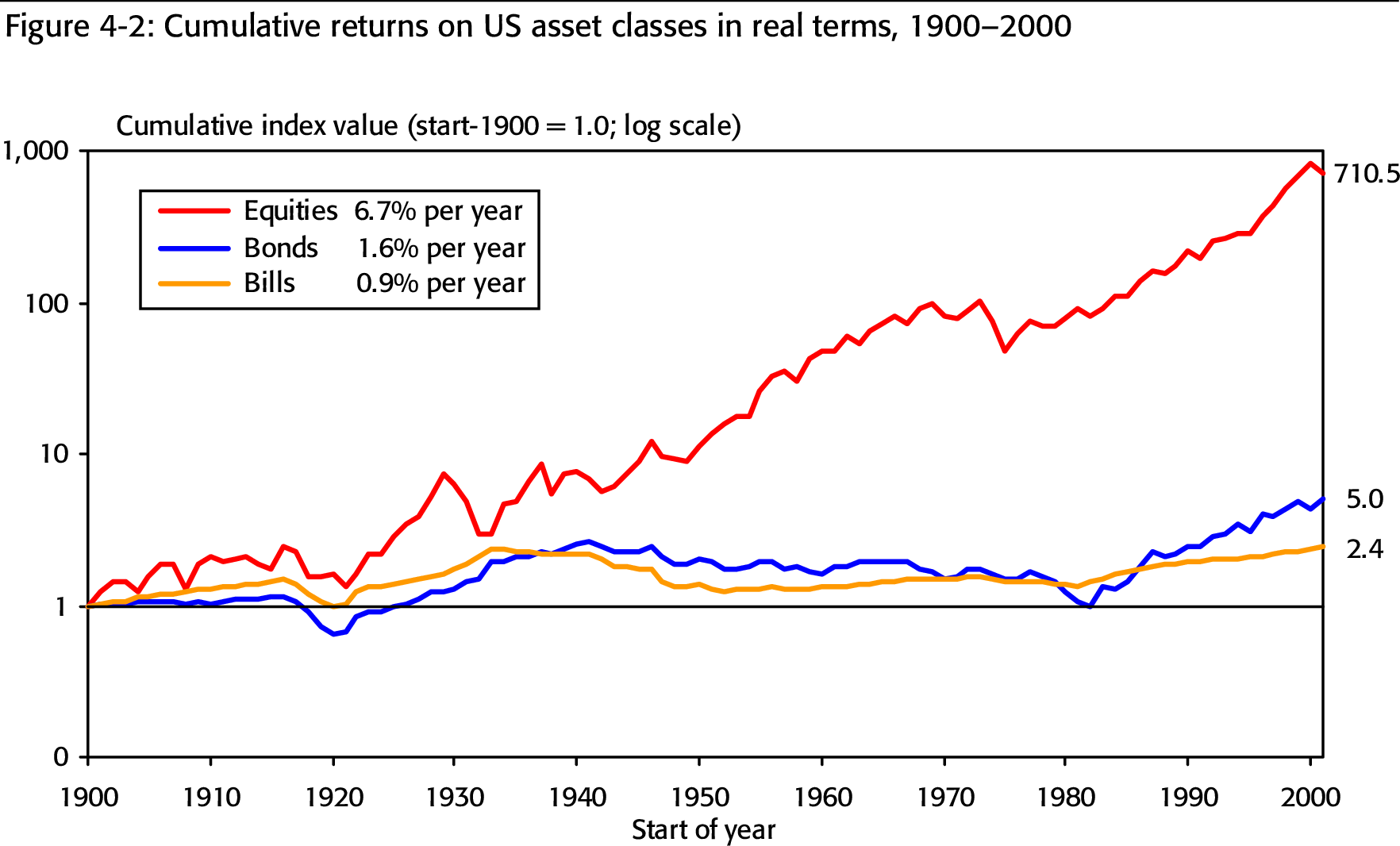

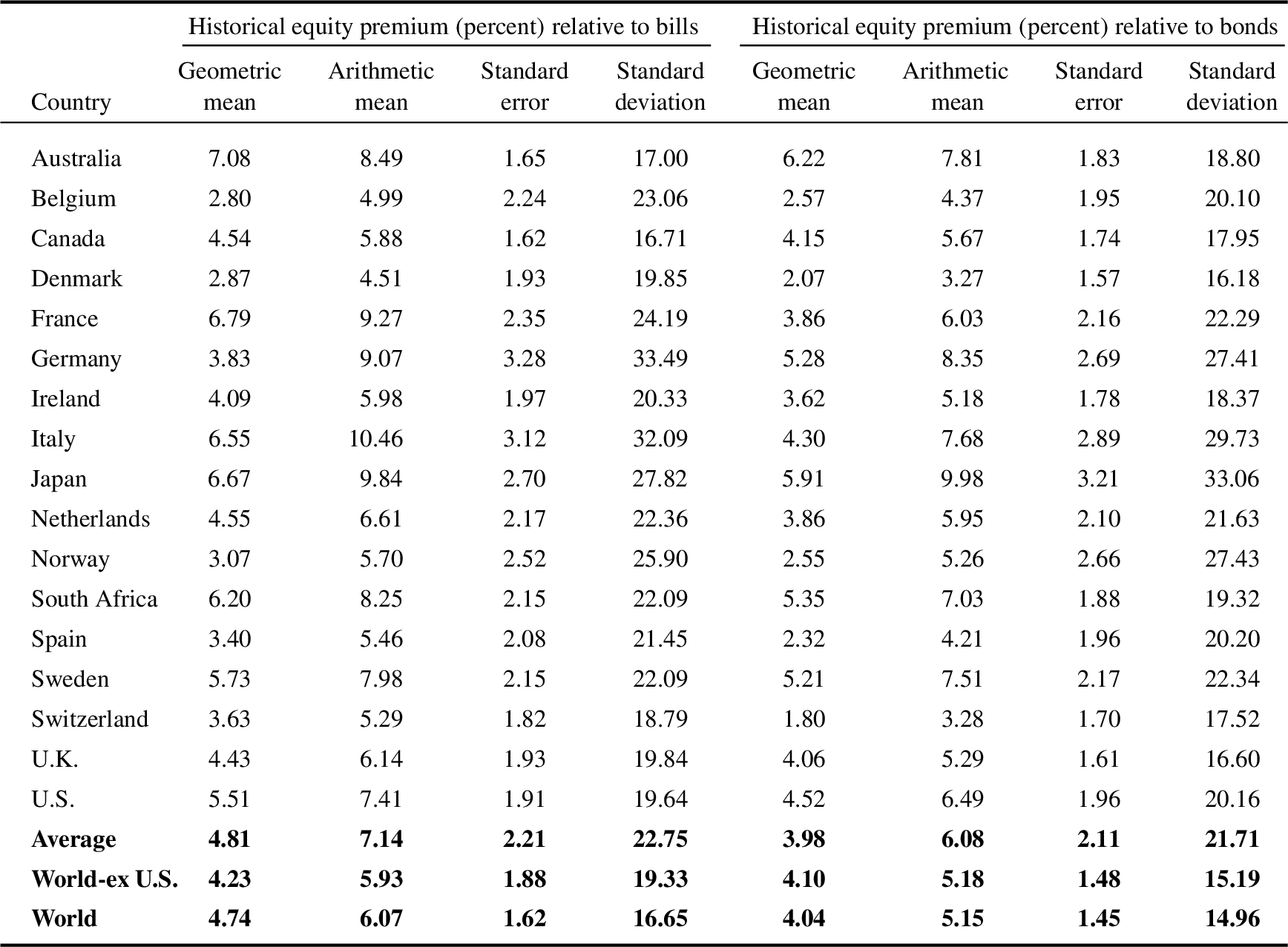

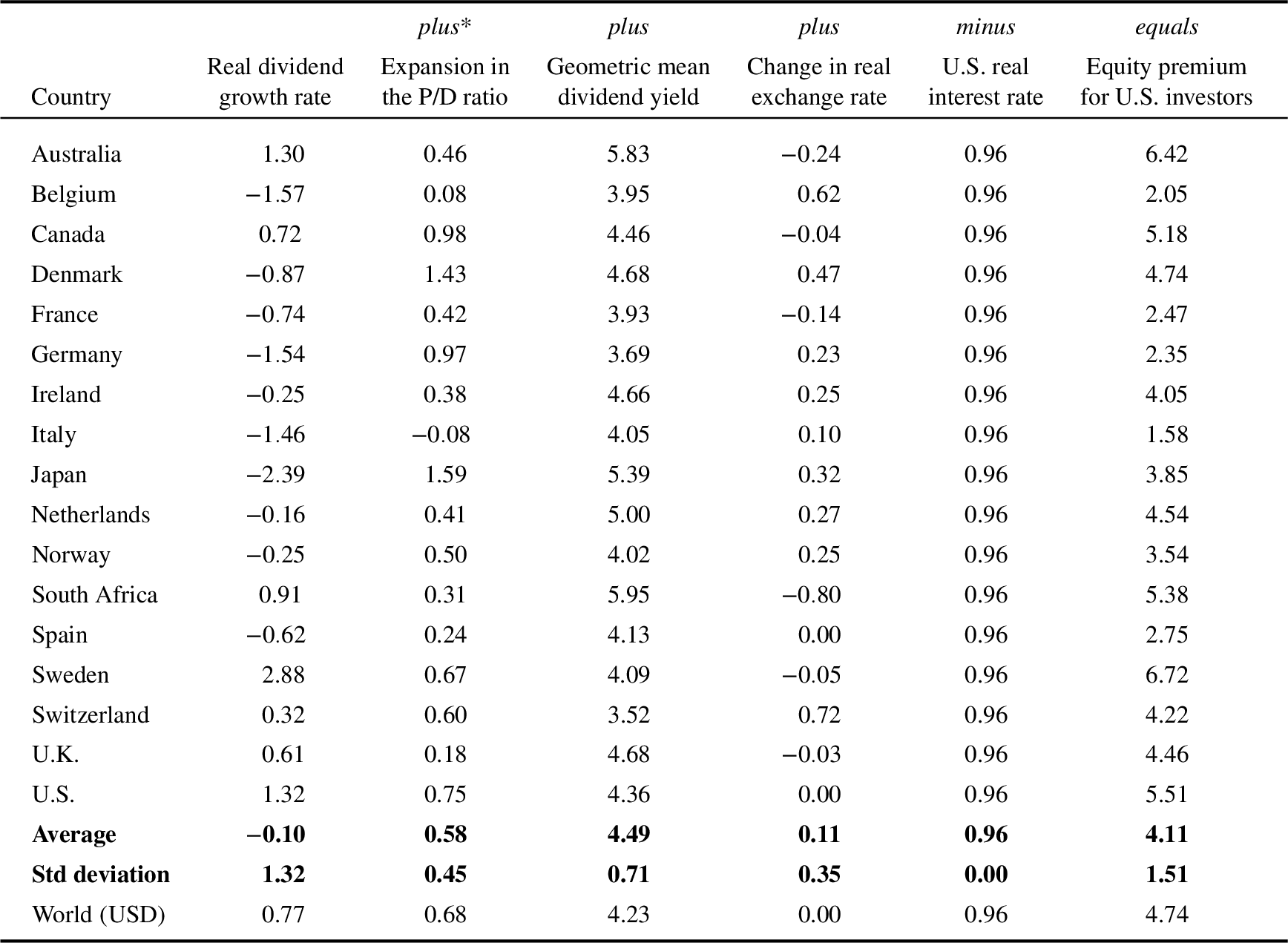

Most interesting result: housing has a much higher sharpe ratio than equities.

Return is roughly similar, but it’s much less risky.

To me it’s another “blow” to the CAPM, which as we now know does not work at all to explain the cross-section of assets.

We are back to one fundamental question: why do bonds have such low returns compared to housing / stocks?

Question: is the preformance we measure one that was to be expected or not?