Lecture 1 - Introduction to Superstars

UCLA - Econ 19 - Fall 2018

Basic Information

Lectures: Tuesdays 2-3:50 pm. Sessions every two weeks, starting Week 1: Oct 2, Oct 16, Oct 30, Nov 13, Nov 27. Bunche Hall 3170. To pass this class, you are required to come to all five classes from beginning to end (per university regulation, because our classes are 2-hour classes). Please make sure you can make all five dates before you enroll in this class.

Course Website: https://fgeerolf.com/econ19/

Moodle Website: https://moodle2.sscnet.ucla.edu/course/view/18F-ECON19-1

Course description. Bradley Cooper, Angelina Jolie, Katy Perry, Tiger Woods, Tim Cook, Marissa Mayer, and all earned more than 10 million dollars last year according to Forbes. That is more than 300 times the median wage in the United States. Can economics make sense of these orders of magnitudes? Who among a famous singer, a CEO running an international organization on several continents, an entrepreneur creating Microsoft, Apple or Facebook, or a successful Wall Street trader, creates more “economic value”? Should inventors, top managers and CEOs be rewarded more than rock stars or professional athletes? What are the arguments for and against counteracting the corresponding increases in inequalities through taxation or other government interventions? Can we expect the rising “winner-takes-all” trend to continue? The Fiat Lux class Economics of Superstars should be a playful way to first approach basic economic concepts (optimality, incentives, Pareto distributions, public goods, complementarities, etc..), and to test the power of economic reasoning as well as its limits.

Grading. P/NP basis, based on attendance and 30 mn presentations by groups of 2 or 3, during the last two sessions (Week 7 and Week 9). To pass this class, you are required to come to all five classes from beginning to end (per university regulation, because our classes are 2-hour classes). Please make sure you can make all five dates before you enroll in this class.

Required readings before classes start. Sherwin Rosen (1938-2001), whom the title of this course is borrowed from, wrote about superstars in The American Scholar in 1983, following his celebrated American Economic Review paper in 1981 (listed under “To go further”). You are required to read this piece before classes start:

Main Readings. The material for presentations during the last 2 classes can be found in the following eight academic articles. These are articles from the Journal of Economic Perspectives, in complimentary access from the American Economic Association’s website. They will be assigned on a first come, first served basis. Please email-me the number of the paper you wish to present, as well as the name of your partner(s):

Alvaredo, Facundo, Anthony B. Atkinson, Thomas Piketty, and Emmanuel Saez. “The Top 1 Percent in International and Historical Perspective.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 3 (September 2013): 3–20. pdf / html

Kaplan, Steven N., and Joshua Rauh. “It’s the Market: The Broad-Based Rise in the Return to Top Talent.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 3 (September 2013): 35–56. pdf / html

Bivens, Josh, and Lawrence Mishel. “The Pay of Corporate Executives and Financial Professionals as Evidence of Rents in Top 1 Percent Incomes.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 3 (September 2013): 57–78. pdf / html

Mankiw, N. Gregory. “Defending the One Percent.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 3 (September 2013): 21–34. pdf / html

Corak, Miles. “Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 3 (September 2013): 79–102. pdf / html

Bonica, Adam, Nolan McCarty, Keith T. Poole, and Howard Rosenthal. “Why Hasn’t Democracy Slowed Rising Inequality?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 3 (September 2013): 103–24. pdf / html

Philippon, Thomas, and Ariell Reshef. “An International Look at the Growth of Modern Finance.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 2 (May 2013): 73–96. pdf / html

Haskel, Jonathan, Robert Z. Lawrence, Edward E. Leamer, and Matthew J. Slaughter. “Globalization and U.S. Wages: Modifying Classic Theory to Explain Recent Facts.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 26, no. 2 (May 2012): 119–40. pdf / html

Lighter Reading. The following pieces are written by academic economists for a broader audience:

Kenneth Rogoff. “Public Applauds Huge Salaries for Sports Stars while Business Stars Get Abuse.” The Guardian. March 2, 2012. html

Alan B. Krueger. “Land of Hope and Dreams: Rock and Roll, Economics, and Rebuilding the Middle Class. Remarks at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.” June 12, 2013. html

Paul Krugman. “Trade and Inequality, Revisited.” Vox EU. June 15, 2007. html

Press articles. The rise in top incomes is very much in the news these days. Here is a choice of press articles on the subject:

Eduardo Porter. “How Superstars’ Pay Stifles Everyone Else.” New York Times. December 26, 2010. html

John Cassidy. “Forces of Divergence.” New Yorker. March 31, 2014. html

Lizzie Widdicombe. “The Programmer’s Price.” New Yorker. November 24, 2014. html

Books (Optional). To go further, you may want to read the following related references:

Goldin, Claudia, and Lawrence F. Katz. The Race Between Education And Technology. Harvard University Press, 2008.

Moretti, Enrico. The New Geography of Jobs. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future. W. W. Norton & Company, 2012.

Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press, 2014. html

Krueger, Alan. Rockonomics: A Backstage Tour of What the Music Industry Can Teach Us about Economics and Life. Penguin, 2019. html

To go further (Optional). My goal will be to try to convey economic intuitions with the minimum amount of mathematical formalism. However, you may want to try reading the corresponding academic articles yourself. They are very often very mathematical, and I certainly do not expect you to understand their technical derivations. But the introductions and conclusions usually translate the mathematics into words, and can actually be fascinating to read. For example, I advise you to read Sherwin Rosen’s introduction to his AER article The Economics of Superstars. (it is the first reference below) You should also find Handbook chapters and to a lesser extent, the Annual Review of Economics, way more accessible. Again, clicking on the titles should redirect you directly to a download page. Should the links be dead, the articles are also available from a computer connected to the UCLA Wifi, for example through Jstor http://www.jstor.org/ or directly on Google Scholar https://scholar.google.com/:

Rosen, Sherwin. “The Economics of Superstars.” The American Economic Review 71, no. 5 (1981): 845–58. pdf / html

Hamlen, William A. “Superstardom in Popular Music: Empirical Evidence.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 73, no. 4 (1991): 729–33. html

Krueger, Alan B. “The Economics of Real Superstars: The Market for Rock Concerts in the Material World.” Journal of Labor Economics 23, no. 1 (January 1, 2005): 1–30. html

Connolly, Marie, and Alan B. Krueger. “Chapter 20 Rockonomics: The Economics of Popular Music.” In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture, edited by Victor A. Ginsburg and David Throsby, 1:667–719. Elsevier, 2006. html

Malmendier, Ulrike, and Geoffrey Tate. “Superstar CEOs.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124, no. 4 (November 1, 2009): 1593–1638. html

Alan Krueger’s New York Times Piece

In statistical jargon, the cascade of information and musical preferences through networks of fans generates a power-law distribution of popularity: the popularity of the most popular item is a multiple of the next-most-popular item, and so on.

Mathematically, this copycat procedure will result in a small number of songs responsible for most of sales. In 2016, the most popular artist, Drake, was streamed 6.1 billion times, followed by Rihanna (3.3 billion streams), Twenty One Pilots (2.7 billion streams) and The Weeknd (2.6 billion streams). Moving down a hundred places from Drake, the 101st-ranked group was the California band Los Tigres del Norte, which was streamed 0.5 billion times, or less than 10 percent as much as Drake. The sharp drop-off near the top is characteristic of a power law.

It is easy to see the hand of supply and demand in the rise of inequality, but the reverberations of political, corporate and social choices are also important. For example, cities and states that have raised their minimum wages have boosted earnings for low‑paid workers and reduced inequality.

Laments the highly skewed nature of the business:

Is there anything else we can learn from the music industry? When I saw the multitalented Questlove, leader of the Roots, in Miami Beach recently, he lamented the highly skewed nature of the business. “In my world I’d just like to see a balance,” he told me. “It’s like just one person and no one else. And whoever is the most digestible gets that spotlight and that attention. Meanwhile, there are zillions and jillions of artists who are just as worthy of getting these things. My position is, more or less, while the spotlight is still warm, to show people options.”

Questions asked

“Behind every great fortune lies a great crime.” (Honoré de Balzac)

Some defining features of “Superstar Economics”

During this first course, we start discussing around Sherwin Rosen’s Economics of Superstars article in The American Scholar. Sherwin Rosen (1938-2001) was a great American labor economist, who might have gone on to win the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. Sherwin Rosen’s general audience article on The Economics of Superstars is very dense and has very much to it, but Sherwin Rosen discusses a number of strong points which we shall come back to.

He argues that markets where superstars are important are characterized by a number of common features, which we go through next:

- Superstars can earn extra-ordinary sums.

- The revenues of superstars are very heterogeneous.

- Superstar operate on a scale so large that the market is divided over a handful of participants.

To summarise, markets where superstar economics operate are characterized by large, unequal incomes, which are distributed among a handful of participants. We develop each one of these arguments next.

Large revenues for superstars

Sherwin Rosen’s superstar paper was written in 1983, therefore, all the orders of magnitude that he gives need to be adjusted to be comparable to today’s numbers. There are two main reasons why his 1.2 million figure for a basketball player on a losing team needs to be adjusted. First, there has been considerable price inflation in the United States since 1983, so that 1.2 million in 1983 could buy much more then than it can buy now. Second, there has been quite a lot of per capita GDP growth as well, so that on average people were much poorer in 1983, which makes the 1.2 million figure even more impressive.

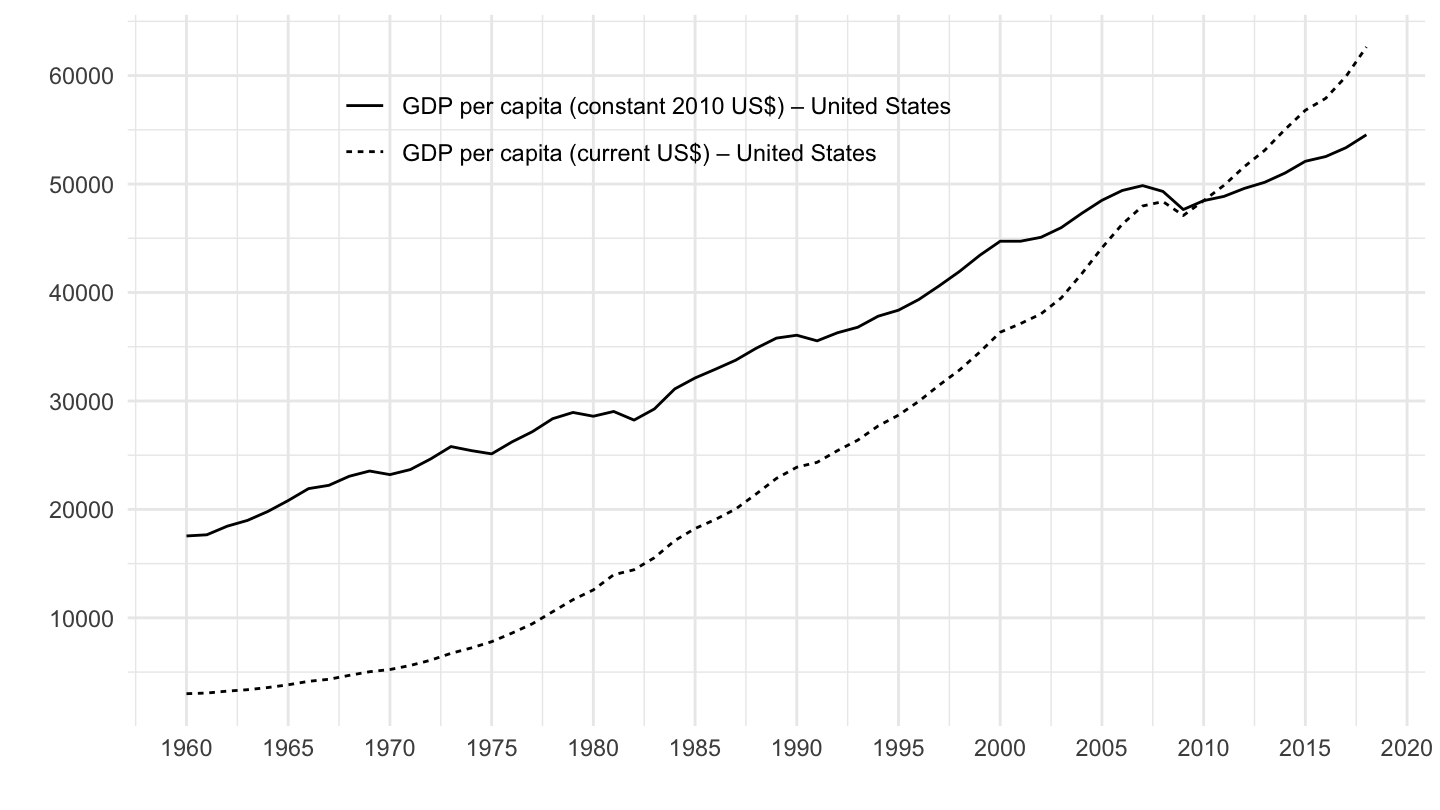

Using the time series of GDP per capita in current U.S. dollars allows to account for both problems at the same time. One may find one such series at the following link: https://db.nomics.world/WB/WDI/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD-US. The data which is then obtained is plotted below. I also give the values for GDP per capita (as well as, for your information, the values for Real GDP per capita, in 2010 dollars).

A simple proportional rule allows us to conclude that in order to convert 1983 dollars to 2017 dollars, taking into account inflation as well as per capita GDP growth, we need to multiply by a factor of 59531.66/15561.43 = 3.83. Table 1 shows the numbers used to make that calculation.

Figure 1: Real GDP Per Capita.

| year | GDP per capita | Real GDP per capita |

|---|---|---|

| 1983 | 15,544 | 29,261 |

| 1990 | 23,889 | 36,059 |

| 2000 | 36,335 | 44,727 |

| 2010 | 48,467 | 48,467 |

| 2017 | 59,928 | 53,356 |

This allows to convert Sherwin Rosen’s examples as follows.

| Star | 1983 Income | 2017 Income |

|---|---|---|

| Basketball player on a losing team | 800,000 | 3,060,472 |

| Television interviewer | 2,000,000 | 7,651,181 |

| Typical NBA Player | 250,000 | 956,398 |

| Boxer of championship caliber (Sugar Ray Loonard) | 30,000,000 | 114,767,717 |

Heterogeneous revenues for superstars

Large scale for superstars

The “scale” that superstars are able to reach is so potentially large that the whole market size is in fact divided over a only a handful of participants in all activities that superstars are engaged in:

The first thing to be said in this connection is that certain economic activities admit extreme concentration of both personal reward and market size among a handful of participants. Every economic activity supports considerable diversity of talent and significant inequality in the personal distribution of rewards. Activities where superstars are found differ from those in which most of us make our livings by supporting much less diversity and much more inequality, in the distribution of earnings. The bulk of earnings goes to relatively small numbers of practitioners-typically, the few regarded as among the best in their fields.

Sherwin Rosen also notes that industrial firms are typically not allowed to operate at such large scales - because of worries that this would prevent needed competition. Indeed, there are laws against antitrust, which are supposed to constrain firms in their ability to raises prices, which might be detrimental for consumers. However, no such restrictions exist for individuals, who however are often disproportionately dominating the market that they operate in (at a moment in time, there are only a handful of singers who are able to fill in a large stadium):

Similar distributions of earnings in the industrial sector would ultimately come to the attention of the Federal Trade Commission or the Justice Department, but so far as I know, proceedings in restraint of trade were never brought against Caruso, Babe Ruth, Picasso, or the Beatles.

Because of such scales, many would-be superstars actually never make it to the top. For example, in boxing, while Sugar Ray leonard has retired after a relatively brief carrer with wealth on the order of $30 million, others struggle:

The median boxer cannot even make a living at the game an difficulty generating more than a few thousand per year. Only hopefuls, including both those with genuine prospects and those have not yet perceived how dim their prospects really are, can sustain interest and commitment in boxing at those earnings.

These superstar phenomena imply that:

The National Basketball Association has about 250 players; there is probably a lesser number of tournament- quality golfers and tennis players; and there are at most a few dozen highly successful boxers. The number of people attempting to break into the top echelons is larger by many orders of magnitude.

The reward structure is highly nonlinear in measurable talent and ability

Sherwin Rosen notes that where superstars are found, the scale of rewards appears to rise more than proportionately with talent and ability.

These examples point to another characteristic of the activities where superstars are found. Rewards and the probability of success appear to rise more than proportionately with talent and ability. In this we are on a little dangerous ground because in many instances it is difficult to find objective measures of personal productivity.

Here, Sherwin Rosen is trying to get at an objective measure of different abilities. He notes that abilities are actually not that different, and that a small different can matter a ton. He takes two examples. First, football:

If in football a running back is half a step quicker than the defense, that might have enormous effect on his productivity.

Second, golf:

The top five money winners on the pro golf tour have annual stroke averages that are less than 5 percent lower than the fiftieth or sixtieth ranking players, yet they earn four or five times as much money.

Finally, baseball:

A twenty-game winning pitcher in baseball earns far more than the sum of two ten-game winners.

This is true in music, as well:

Interestingly, income differences between first-rank and second-rank performers are substantial, even though, in a blind hearing, an infinitesimal portion of the audience could detect more than minor differences among them.

Use of audiences / Media audiences

Media attention is paramount:

For the phenomenon of superstar income to exist, certain conditions must exist alongside it. The attention of the media to t he activities in which the superstars engage is one such condition. This becomes evident in the world of show business, of which professional sports might be considered a subset; but it is also evident in arts and letters, two other fields that produce superstars. Show business first. Plausibly informed opinion has it that the number of full-time comedians in the United States does not exceed a few hundred. This is probably a smaller number than was employed in the days of vaudeville. Among contemporary comedians, the most popular are reported to earn extraordinary sums-an d none earn more than those who appear regularly on television. Again, the capacity of television to produce large incomes is manifest in the enormous salaries paid to news broadcasters, especially those who work for t he networks and for stations located in large local markets such as New York and Chicago.

The other element has to do with certain peculiarities in the technology of the production of services through the use of audiences. These activities must admit duplication of a kind so that a person - the superstar - can deliver services to many buyers simultaneously. Once again, here the use of media is instrumental.

Poor talent is an inedequate substitute for superior talent

Wherever superstars are to be found, I believe at least one of two elements will also be found-elements that are necessary to support and sustain both stars and superstars. One element is that the technology of consumption or use of the services provided by the activity must be such that poor talent is an inadequate substitute for superior talent

Sometimes these differences are inherent in the valuations put upon services by buyers. If one surgeon is 10 percent more successful in saving lives than another, who among us would not be willing to pay much more than a 10 percent premium to have the more skillful person perform the operation? A company engaged in a $30 million treble-damages lawsuit is rash to scrimp on the legal talent it engages. Stockholders and directors would look askance at ring mediocre talents under those circumstances.

In the case of the music industry:

Hearing a succession of second- rate singers does not measure up to hearing one outstanding performance by Placido Domingo. Contracting for a legal defense with two lawyers, each of whom would be likely to lose the case half the time, would not elevate the probability of winning much above one-half and may actually decrease it.

Limited costs of duplication

The superstar is someone whose audience is enormous relative to the scale on which most of us operate. Personal markets of that magnitude are almost exclusively sustained by use of media as a cooperating resource. These markets represent technologies that, in effect, allow a person to clone himself at little cost. More precisely, costs do not increase nearly in proportion to market size; and if costs are the same, the more tickets that can be sold is, as they say, all gravy. Once an author delivers a manuscript to a publisher, it can be duplicated at small expense practically indefinitely. A television or radio program is communicated virtually costlessly and identically to whomever happens to tune in. The performer or author puts out more or less the same effort whether one thousand or one million people show up to listen to the concert or buy the book.

Most economic activities are far more constrained in this respect. In the generality of such activities, costs increase more nearly in proportion, or more than in proportion, with output. When this is the case, it is not necessarily advantageous to work on the grand scale. The ultimate constraint here is the limitation of time.

For example, a fancy and nimble dentist might manage to keep himself fully occupied by shifting waiting time to patients, by keeping the waiting room full of patients, and by working three chairs sequentially with several assistants. Many patients remain willing to pay the time and money costs if the services provided are sufficiently good, but imagine what would happen to the concentration of supply of dental services if a practitioner could serve a thousand patients simultaneously.

Because of these limited costs of duplication, we can go a long way:

Here it becomes clear that technologies that enable sellers to cater to mass audiences account for the small number of successful practitioners in the fields we commonly associate with superstars. It just doesn’t take many people to supply the entire market demand for these services when each one can effectively duplicate himself through the media. This, combined with a little market competition, also accounts for why the successful few are among the talent elite and why their incomes are so large. In such economic activities, a person of lesser talent is dominated by a person of greater talent who charges the same price. The greater talent captures all the business, and it is worthwhile to get as much business as possible because costs don’t increase by very much. But the more talented person can do even better. His extra margin of talent allows him to raise prices above what the less talented can charge without losing significant audience and market share. Once again a little extra ability goes a long way. The return on each unit sold may be very small, but total reward is enormous because unit reward is multiplied by a large number. The fundamental limitation on the superstar’s reward is t he potential size of the market out there to be attracted and the relative edge of the superstar’s talent over those of others waiting in the wings - those who are willing to supply services to the market should the occasion arise and who keep trying to do so.

Changes in the technology of communication and control of distribution have decreased the cost of cloning of talent in many areas and contributed substantially to turning mere stars into superstars. Motion pictures, radio, television, phono-reproduction equipment, and other changes in communications not only have generally decreased the real price of entertainment services but also have increased the possible size of each performer’s audience. The effect of radio and recordings on pop singers’ incomes and the influence of television on the incomes of news reporters and professional athletes are good cases in point. There are finer gradations within these categories. Television is a more effective medium for American football than for bowling, and incomes reflect it. Television nevertheless has had an enormous influence oil the fortunes of top bowlers, golfers, and tennis players because it has enabled their markets to become much larger. Nor are these changes confined to the entertainment sector. Reductions in the costs of communication and transportation have expanded potential markets for all kinds of professional services and have allowed many of the top practitioners in the arts, journalism, and elsewhere to work on national and international scales.

Non-routiness

Some tasks can be performed by just anybody. Others cannot:

Some tasks are so routine and so circumscribed by existing practice that nearly any competent person achieves about the same outcome. Others are more difficult, more uncertain, and, this being so, allow greater possibilities for alternative courses of action and decision. Such tasks offer greater scope for superior talent to stand out and make its mark. More capable physicians spend smaller fractions of their time on routine cases and larger fractions on difficult ones than do physicians of more modest ability, and it is socially desirable that they should do so. Untested apprentice jockeys never ride the favorites in big- stakes races.

Questions raised

Sherwin Rosen then raises a few questions which are very relevant for thinking about the economics of superstars.

Why is paid not proportional to the number of hours supplied?

A key feature of the economics of superstars is that unlike in most economic activities, where it looks like every individual is paid in proportion to the number of hours he puts in, superstars seem to earn income without a proportional effort. In these markets, the most successful earn a disproportionate amount, compared to others who struggle.

A salesman’s productivity is easily measured by the value of goods he sells relative to their cost. Payment on commission basis guarantees a roughly proportional relationship between personal productivity and pay (roughly, because most commission systems are not strictly linear). If the nature of competition was such that the person who sold the most in the firm received, say, 80 percent of the firm’s total compensation to salespersons, the distribution of reward would be much more concentrated and skewed to the top ranks than it actually is. But, then, this is precisely what defines a superstar.

Are these levels of income “efficient”?

Sherwin Rosen argues that the compensation of superstars can nevertheless be considered “efficient”.

In a competitive market economy, of which the United States is a tolerable approximation for the purposes of this discussion, competition ensures that workers are paid in proportion to their personal contribution to national output. Were someone paid less than that contribution, a competing firm would bid more for his services. A person perceived as twice as productive receives twice as much. By the standards of the day, this kind of social arrangement is generally thought to be reasonably equitable.

We will investigate more in detail what exactly Sherwin Rosen here means when he says “efficient”. What Sherwin Rosen refers to here is the First Welfare Theorem. This First Welfare Theorem is a confirmation of Adam Smith’s invisible hand: competitive markets tend towards an efficient allocation of resources. By efficient, economists mean here that it is impossible to make any individual better off without making at least one individual worse off. This criterion for efficiency is called Pareto efficiency.

In addition, a central theorem in economics proves that payment by appropriate contribution is the efficient outcome of a decentralized competitive market mechanism under ordinary circumstances. It is efficient in the sense of making the best out of resources available. To be sure, most of us perceive our own talent with a bit acuity than the way others see it, but misperceptions on that score are, with a few exceptions, ones we can live with. Superstar phenomena appear on the surface to be rather different. There a person with edge in talent receives significantly larger rewards. The puzzle is confounded by the fact that the activities in which superstars engage are characterized by an extreme form of competition. Does this suggest that the principle of payment by contribution has been abandoned.

What explains box office appeal?

Sherwin Rosen is very honest about the limits of economics, which can’t explain what explains success.

Here the elusive quality of box-office appeal, or the ability to attract an audience and generate a large volume of transactions, must be confronted. Current and prospective impresarios will find no guidance from economists on what makes for box-office appeal. One might as well consult psychiatrists on how to raise children.

However, some things can still be said of which industries are more prone to seeing superstars, as well as explain why success often lead to more success.

But that doesn’t mean people can’t recognize it when they see it, or that where and when superstars will appear, and to what extent, might not be predictable, even though it is impossible to tell in advance who the lucky ones will be. The general importance of box-office appeal in the creation of superstars should not be underestimated. The jockeys who obtain mounts in the big races need the credential of a winning record. Aspiring, executives cater to a small clientele but still need to attract sufficient attention by past performances to be in the running for the top positions.

Additional questions

More generally, the question is whether there exists such a thing as an individual’s success, which was not created by the hard work of other, less lucky peers. In research, one is struck by how researchers get fame for things they were not alone to invent. For example, John Maynard Keynes’ multiplier analysis very much built on ideas which were circulating at the time among Cambridge circles. (such as the multiplier analysis, that he is now being credit for)

Similarly, Steve Job’s or alternatively, Bill Gates’ success grew from fundamental research in Computer Science, which was largely funded by the government.