Redistributive Policies

Intermediate Macroeconomics - UCLA - Econ 102

François Geerolf

November 19, 2020

The General Theory - Keynes (1936)

Chapter 24 on the vanishing importance of thrift

On death duties

Chapter 24: the vanishing importance of thrift

Channeling dangerous human proclivities

Theory is moderately conservative in its implications

On individualism

Marriner S. Eccles

Interpretation of the 1920s - 1930s Crisis

Marriner S. Eccles: Federal Reserve Chairman, 1934 - 1948.

Interpretation of the 1920s boom, and 1930s depression: there was too much saving.

Therefore, households piled on debt.

Financial sector, lenders: no other game in town.

Sounds familiar? Similar phenomenon during the 2000-2007 boom.

According to him, less inequality would have allowed to avoid this lending, and therefore the financial crisis.

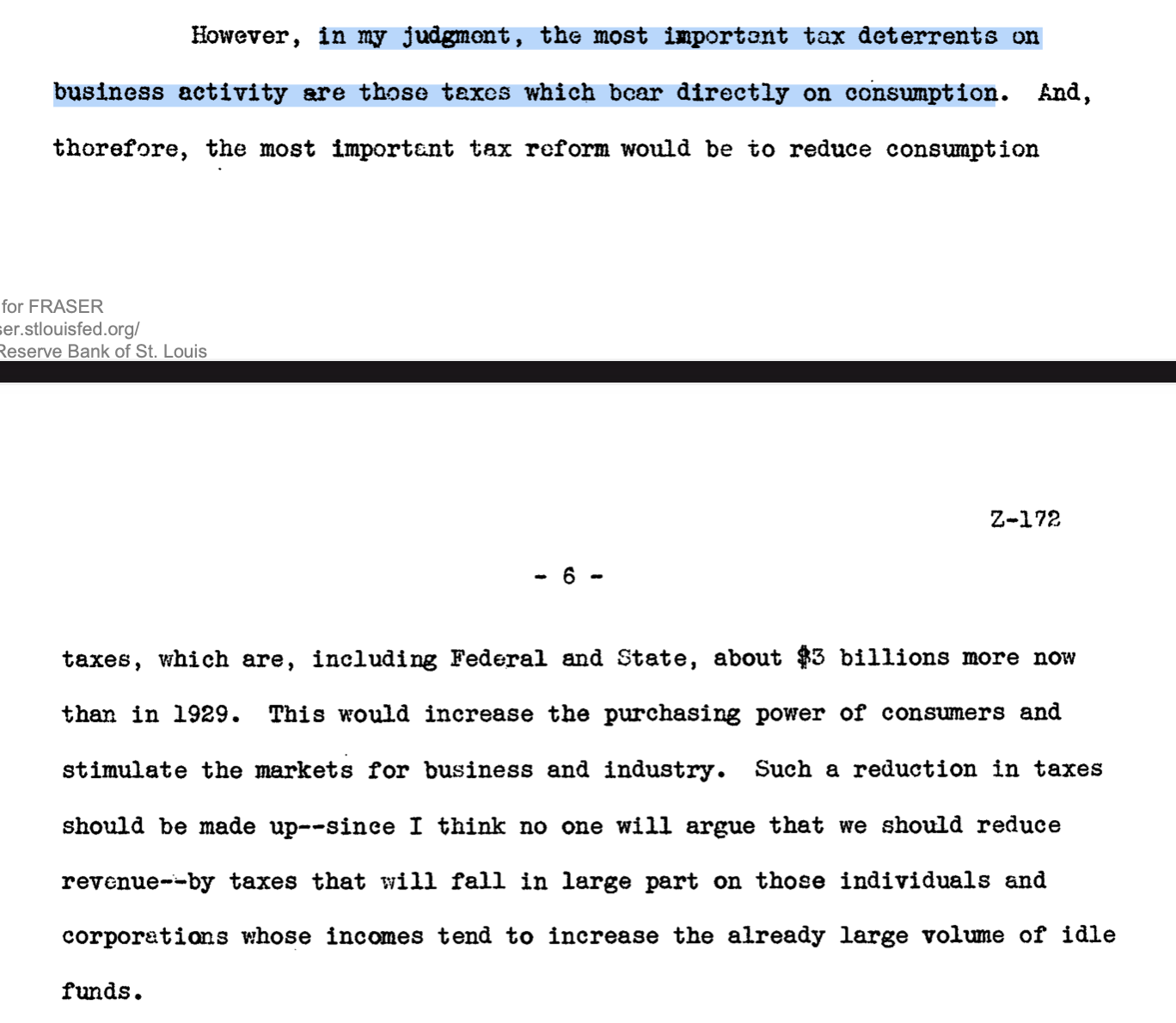

Congressional Testimony, 1933 1/3

- Hearings before the Committee on Finance authorizing and directing the finance committee to make Committee to make an investigation and study of the present’ economic problems of the United States with a view to securing constructive suggestions with respect to the solution of such problems. pdf

Congressional Testimony, 1933 2/3

Congressional Testimony, 1933 3/3

1939 Speech

1939 Speech

1939 Speech

Eccles (1951)

According to Marriner S. Eccles, who was the Federal Reserve Chairman from 1934 to 1948,

The stimulation to spending by debt-creation of this sort was short lived and could not be counted on to sustain high levels of employment for long periods of time. Had there been a better distribution of the current income from the national product — in other words, had there been less savings by business and the higher-income groups and more income in the lower groups — we should have had far greater stability in our economy. Had the six billion dollars, for instance, that were loaned by corporations and wealthy individuals for stock-market speculation been distributed to the public as lower prices or higher wages and with less profits to the corporations and the well-to-do, it would have prevented or greatly moderated the economic collapse that began at the end of 1929.

Eccles (1951)

As mass production has to be accompanied by mass consumption; mass consumption, in turn, implies a distribution of wealth — not of existing wealth, but of wealth as it is currently produced — to provide men with buying power equal to the amount of goods and services offered by the nation’s economic machinery. Instead of achieving that kind of distribution, a giant suction pump had by 1929-30 drawn into a few hands an increasing portion of currently produced wealth. This served them as capital accumulations. But by taking purchasing power out of the hands of mass consumers, the savers denied to themselves the kind of effective demand for their products that would justify a reinvestment of their capital accumulations in new plants. In consequence, as in a poker game where the chips were concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, the other fellows could stay in the game only by borrowing. When their credit ran out, the game stopped.

Eccles (1951)

That is what happened to us in the twenties. We sustained high levels of employment in that period with the aid of an exceptional expansion of debt outside of the banking system. This debt was provided by the large growth of business savings as well as savings by individuals, particularly in the upper-income groups where taxes were relatively low. Private debt outside of the banking system increased about fifty per cent. This debt, which was at high interest rates, largely took the form of mortgage debt on housing, office, and hotel structures, consumer installment debt, brokers’ loans and foreign debt.

Data on Progressivity

Progressivity varies with taxes

Data shows marked differences in progressivity:

Income / Corporate / Estate taxes = quite progressive.

Property / Consumption taxes = less progressive.

I show now the progressivity of different taxes according to the bottom 90% / top 10% dichotomy:

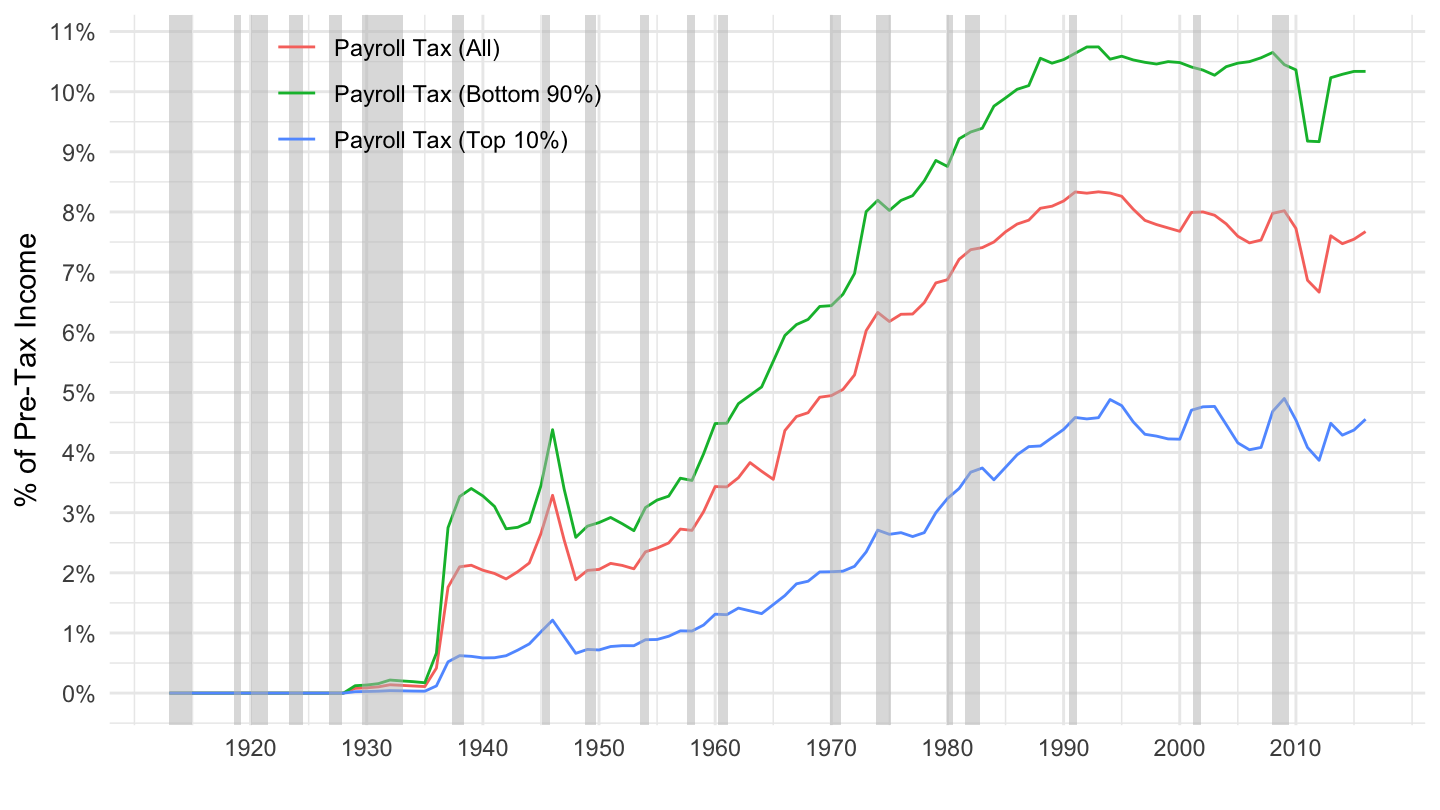

Payroll Tax.

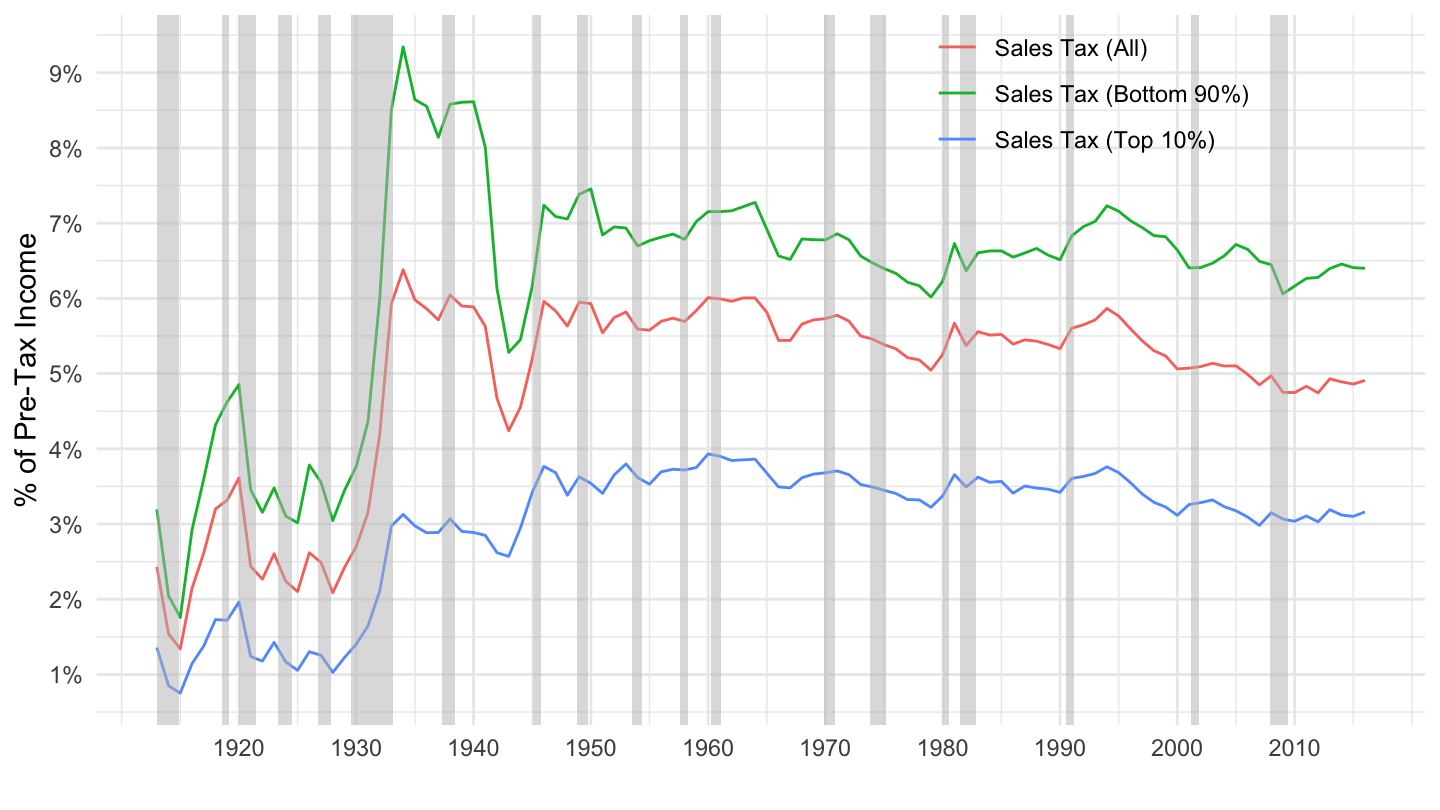

Sales Tax.

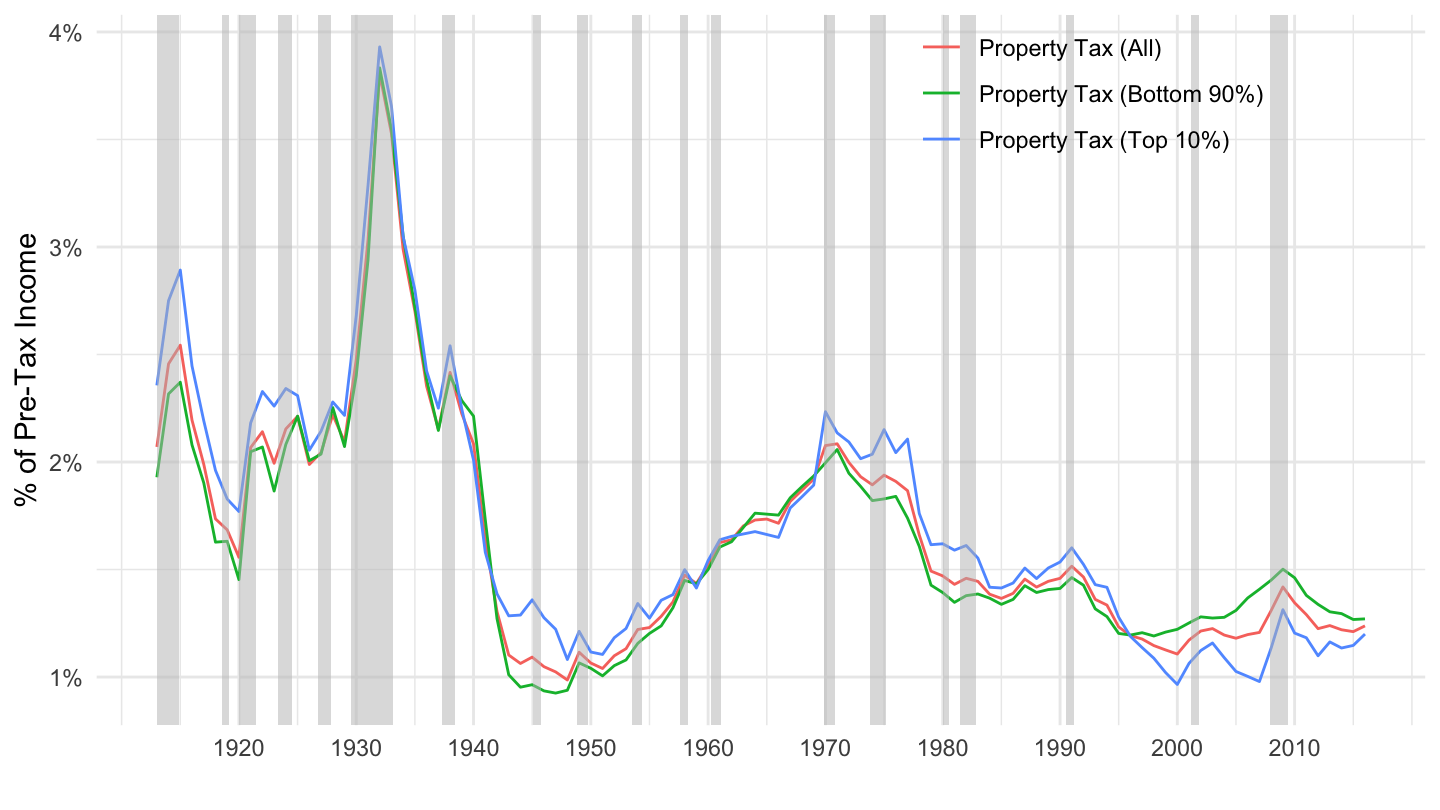

(Residential) Property Tax.

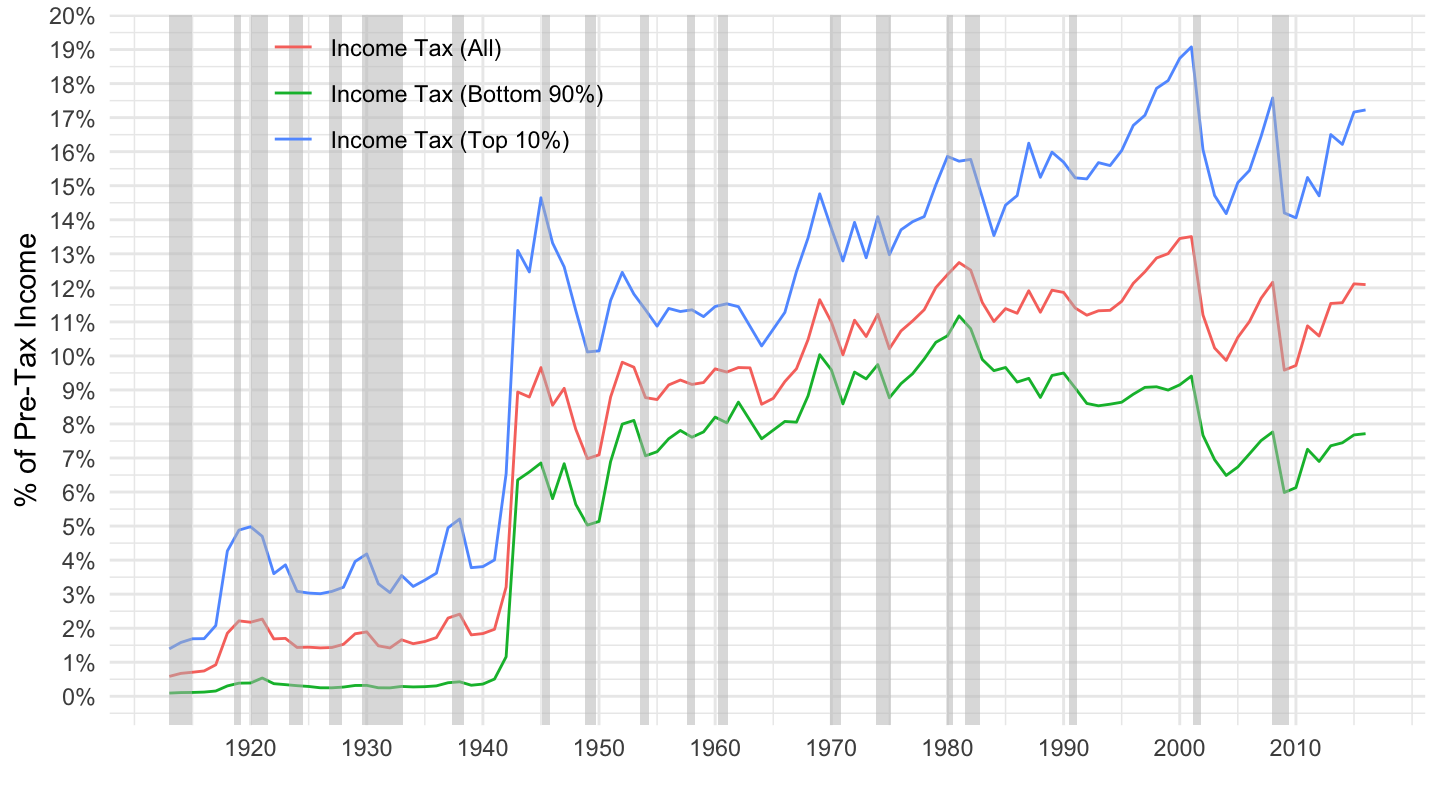

Income Tax.

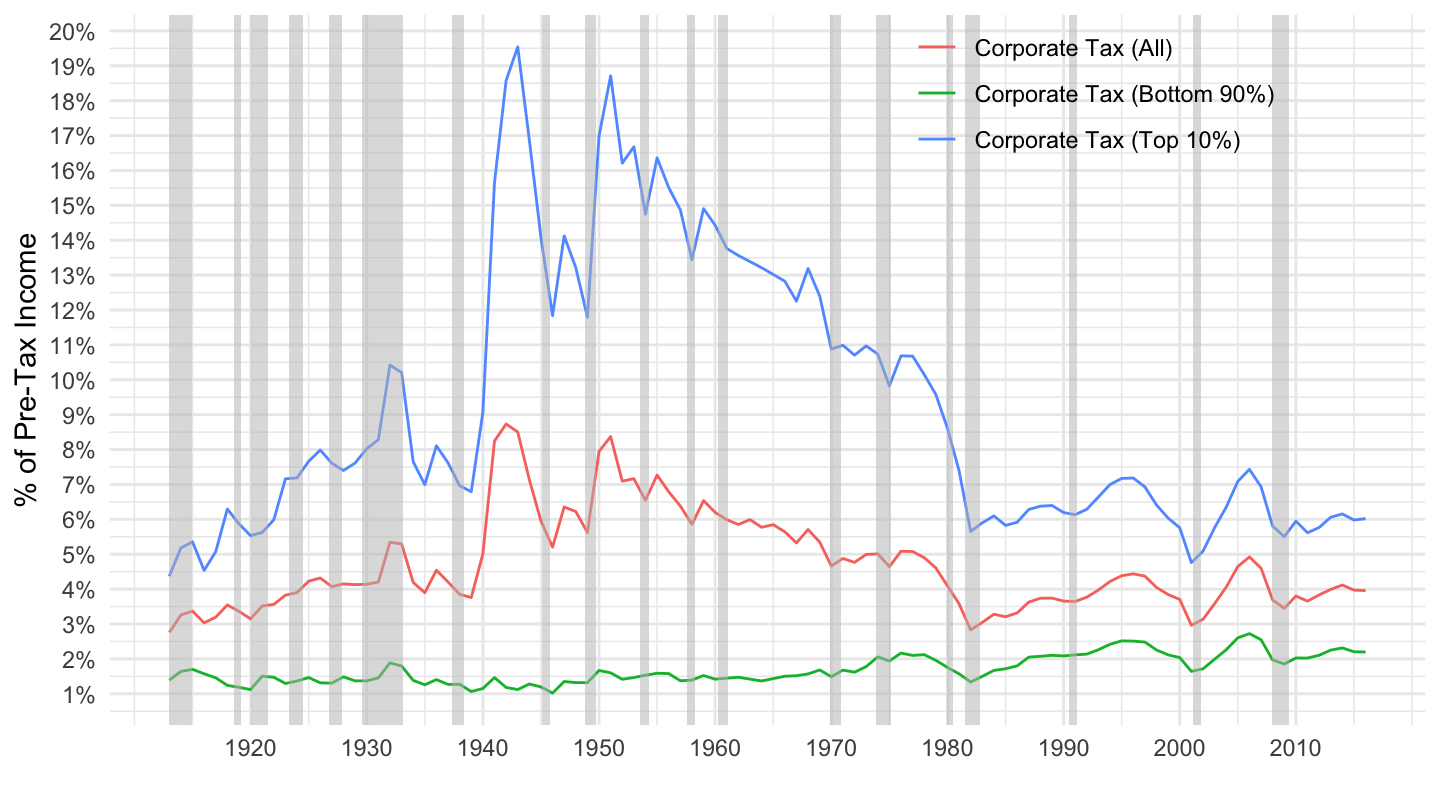

Corporate Tax.

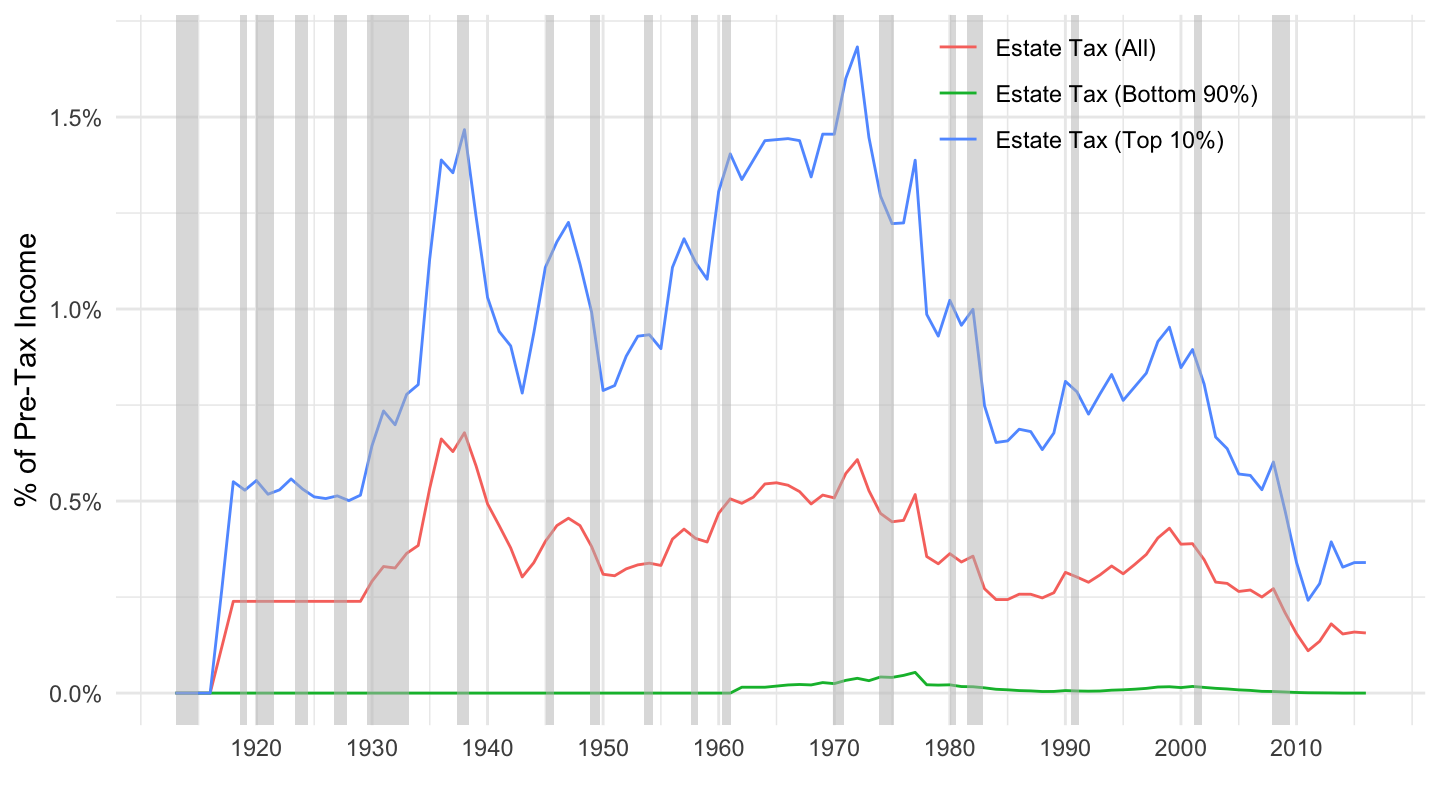

Estate Tax.

Payroll Tax

Sales Tax

(Residential) Property Tax

Income Tax

Corporate Tax

Estate Tax

The Economic Consequences of the Peace - Keynes (1919)

Keynes (1919)

Keynes (1919)

First Transcontinental Railroad

Keynes (1919)

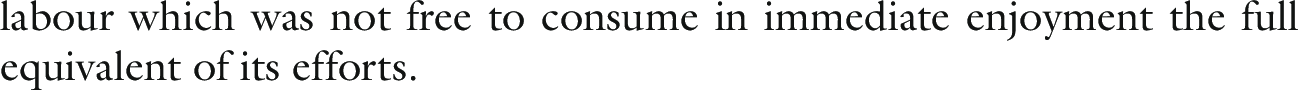

Macroeconomic Performance of U.S. Presidents

Blinder and Watson (2016) - AER

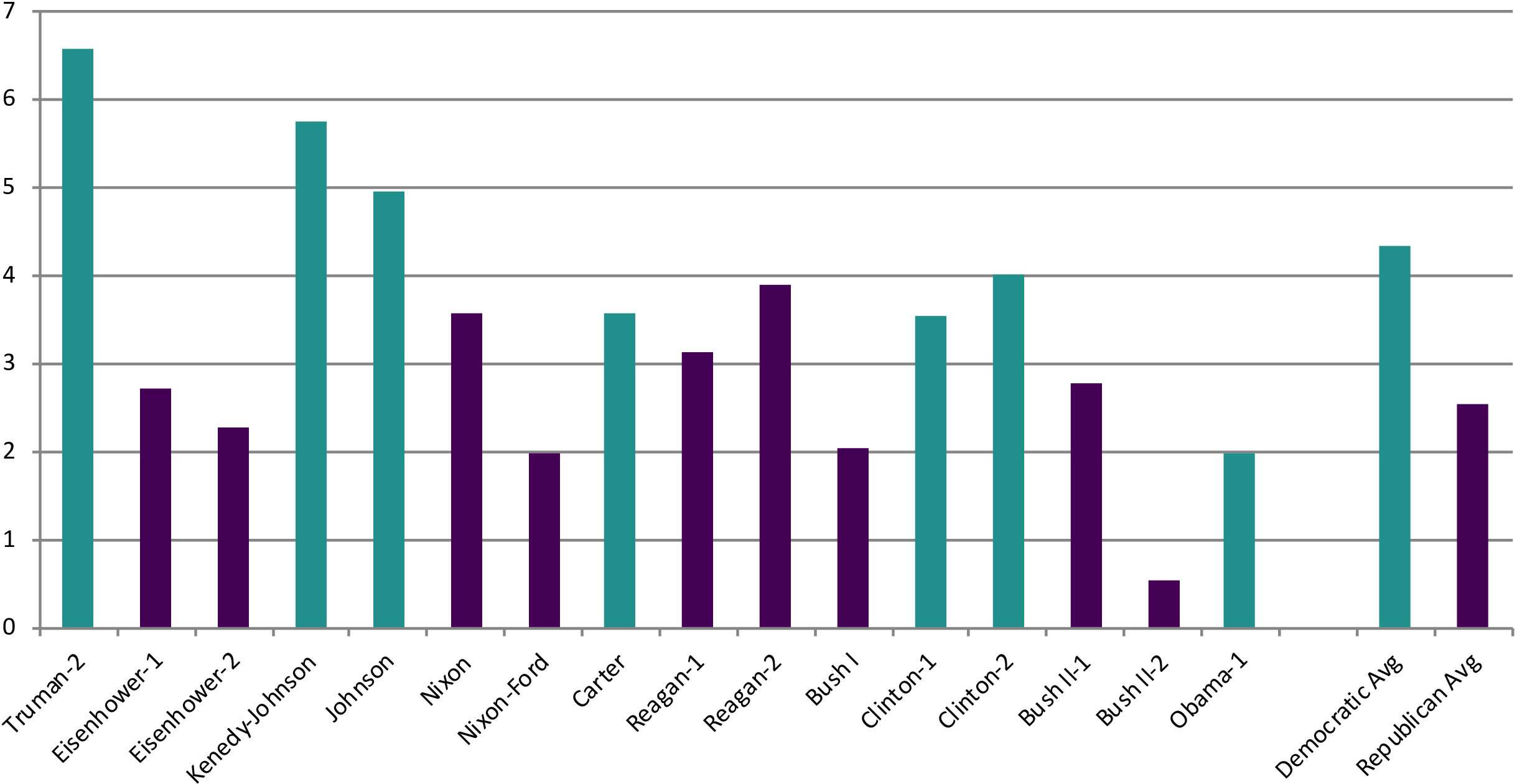

Performance for each president

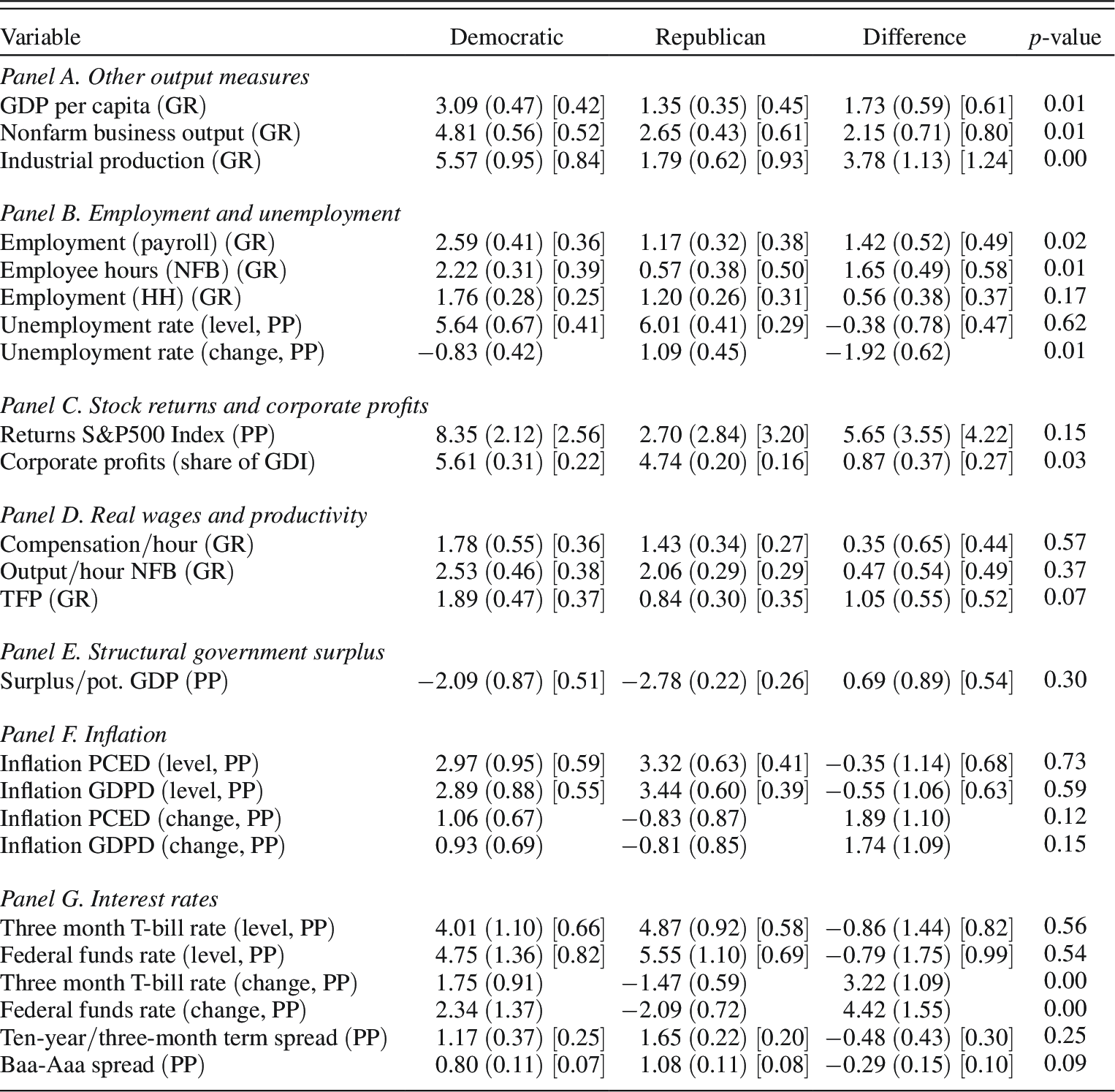

Comparing other outcomes

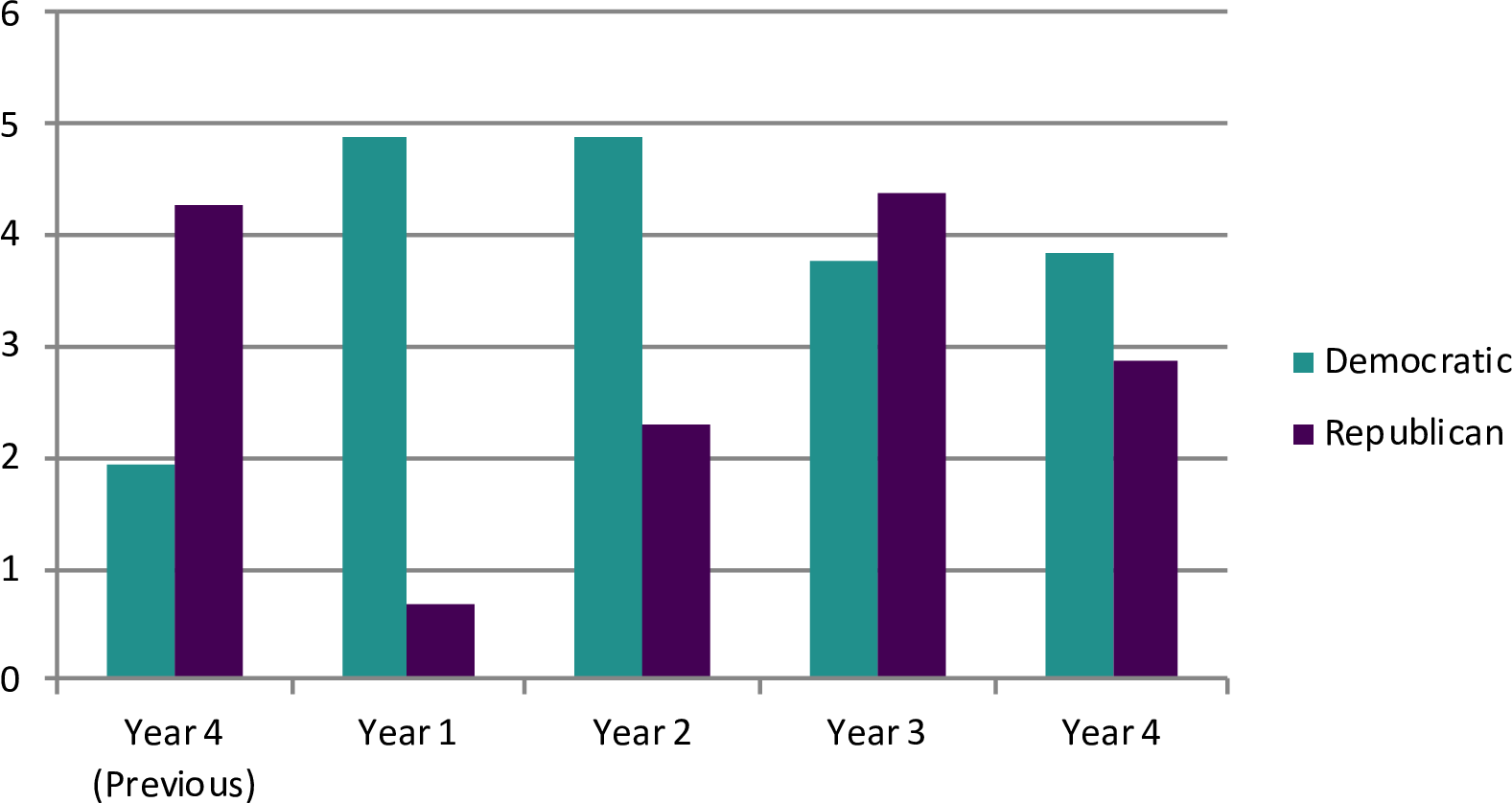

By year in presidency

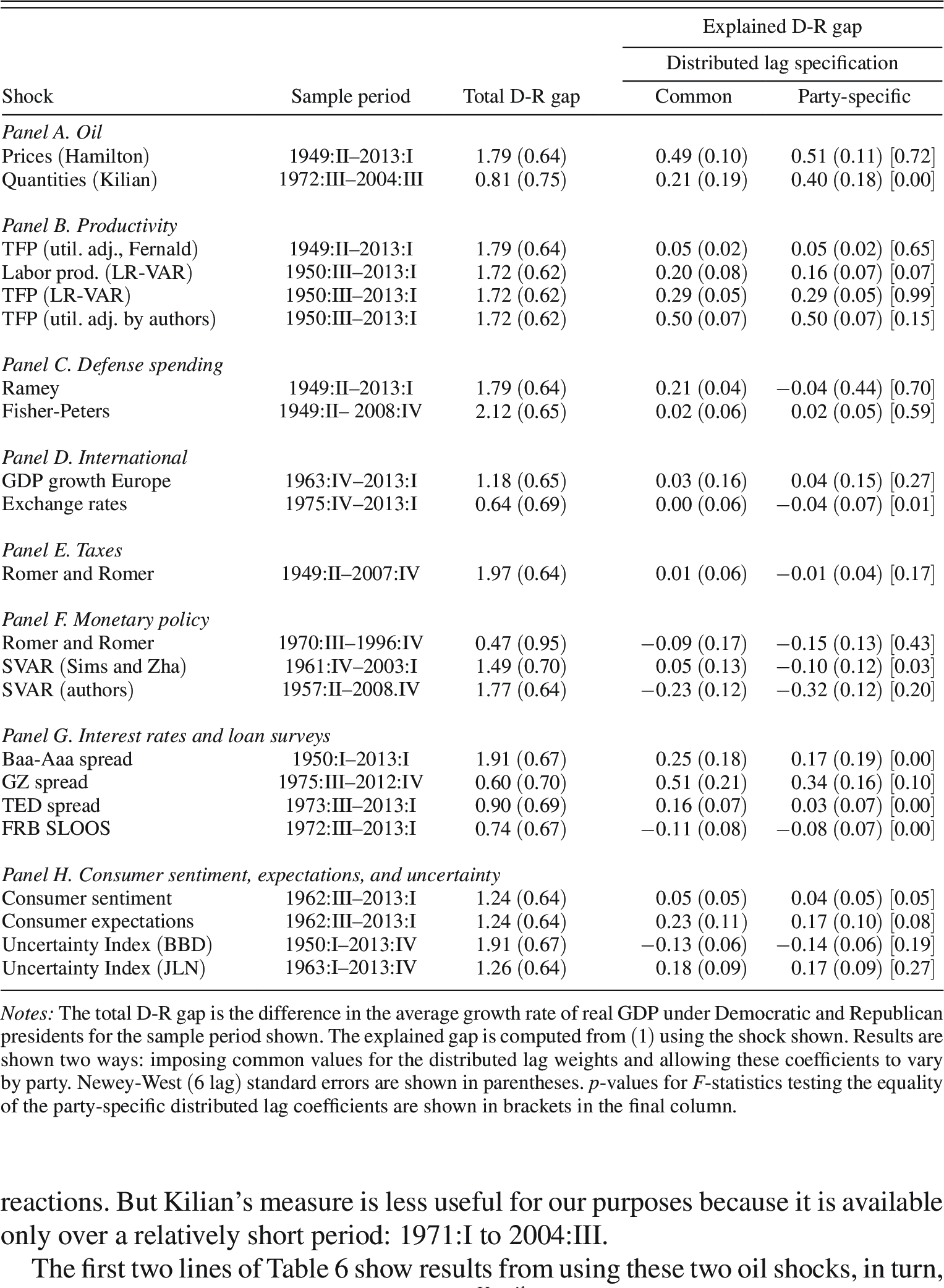

Determinants

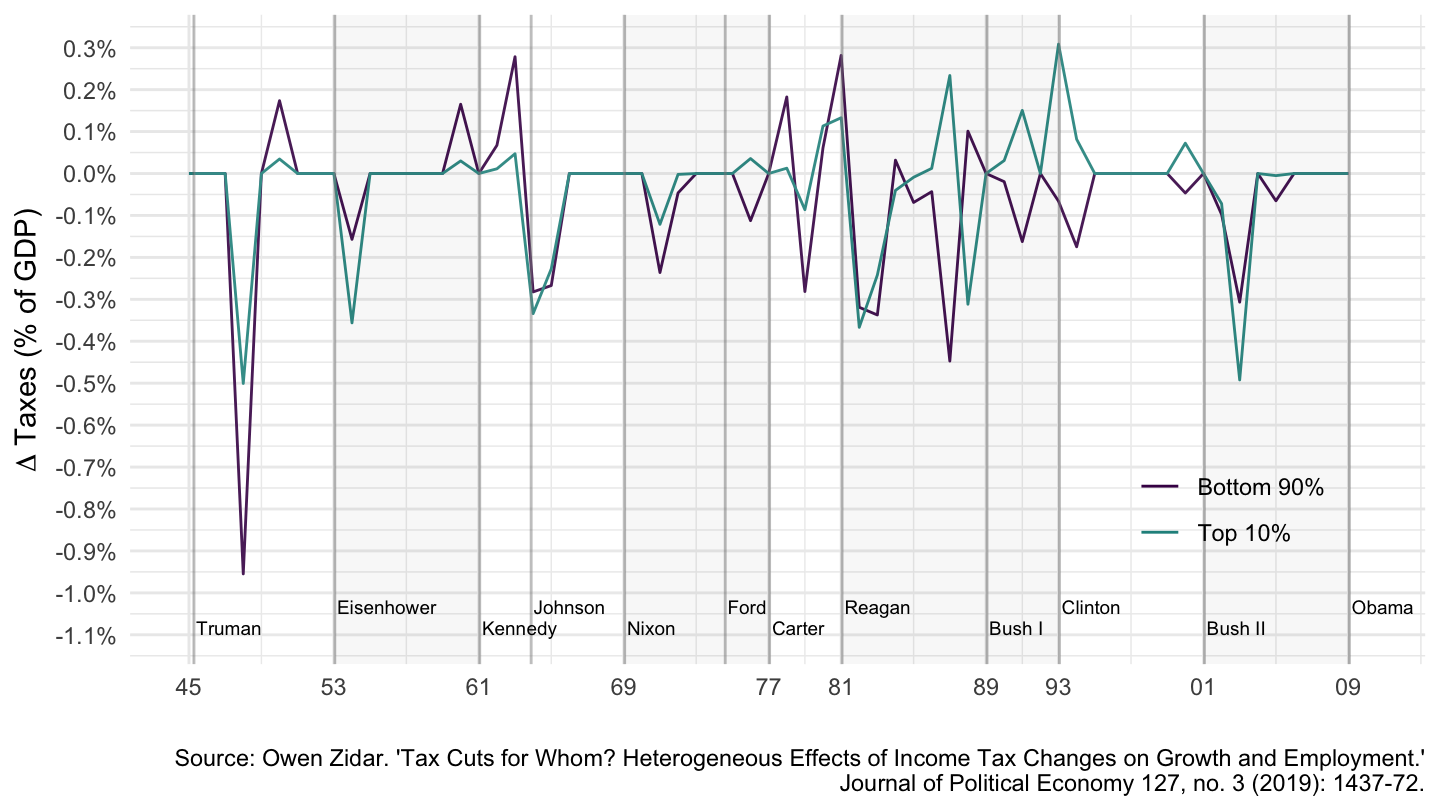

Different Fiscal Policies?

One explanation could be different fiscal policies.

However, according to Romer, Romer (2010), both democrats and republicans have equally accommodative fiscal policy.

Another interpretation: Republicans’ tax cuts are typically more favoring the top 1% than Democrats’ tax cuts. See the lecture on redistributive policies.

Clinton’s and Kennedy’s expansions can be interpreted in that way.

Zidar (2019)

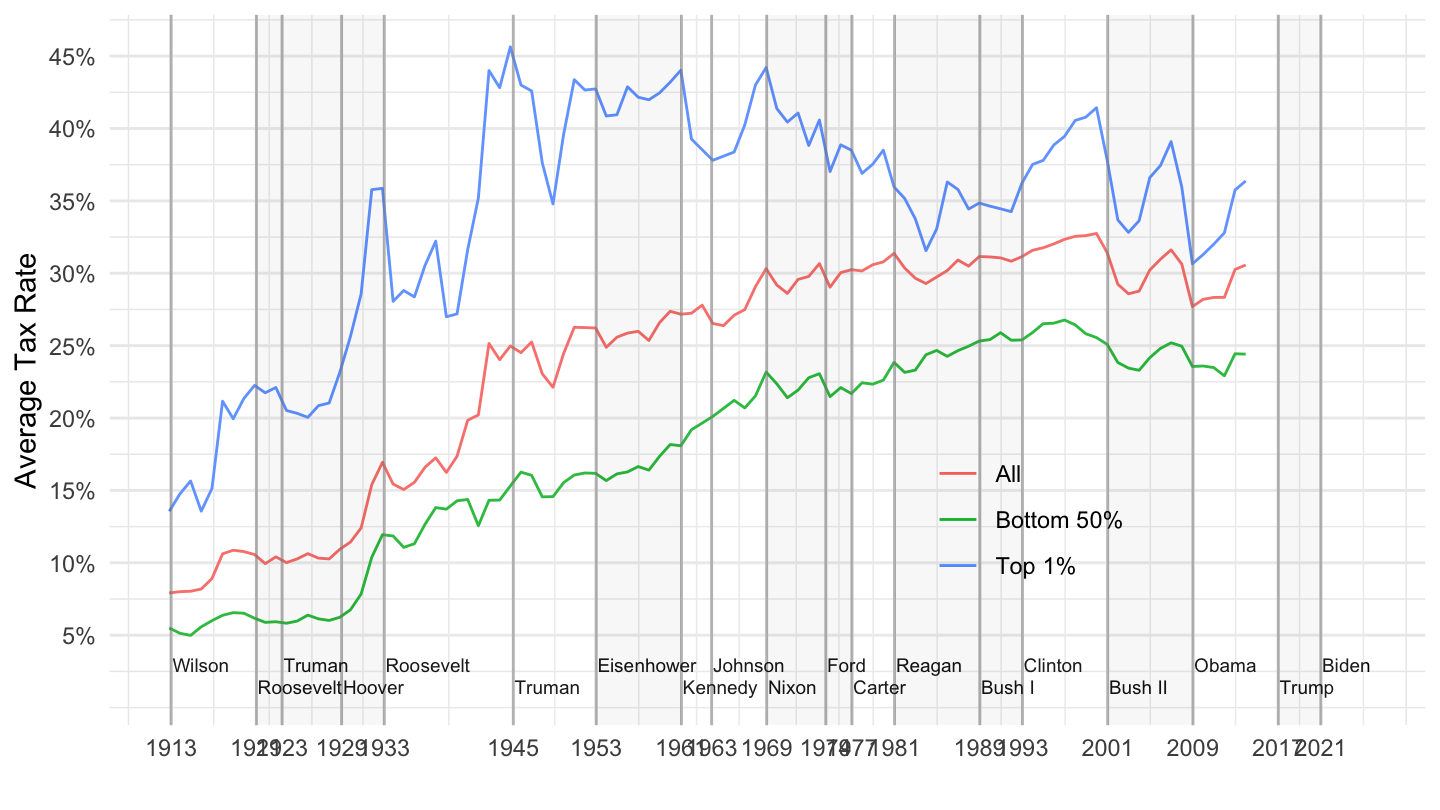

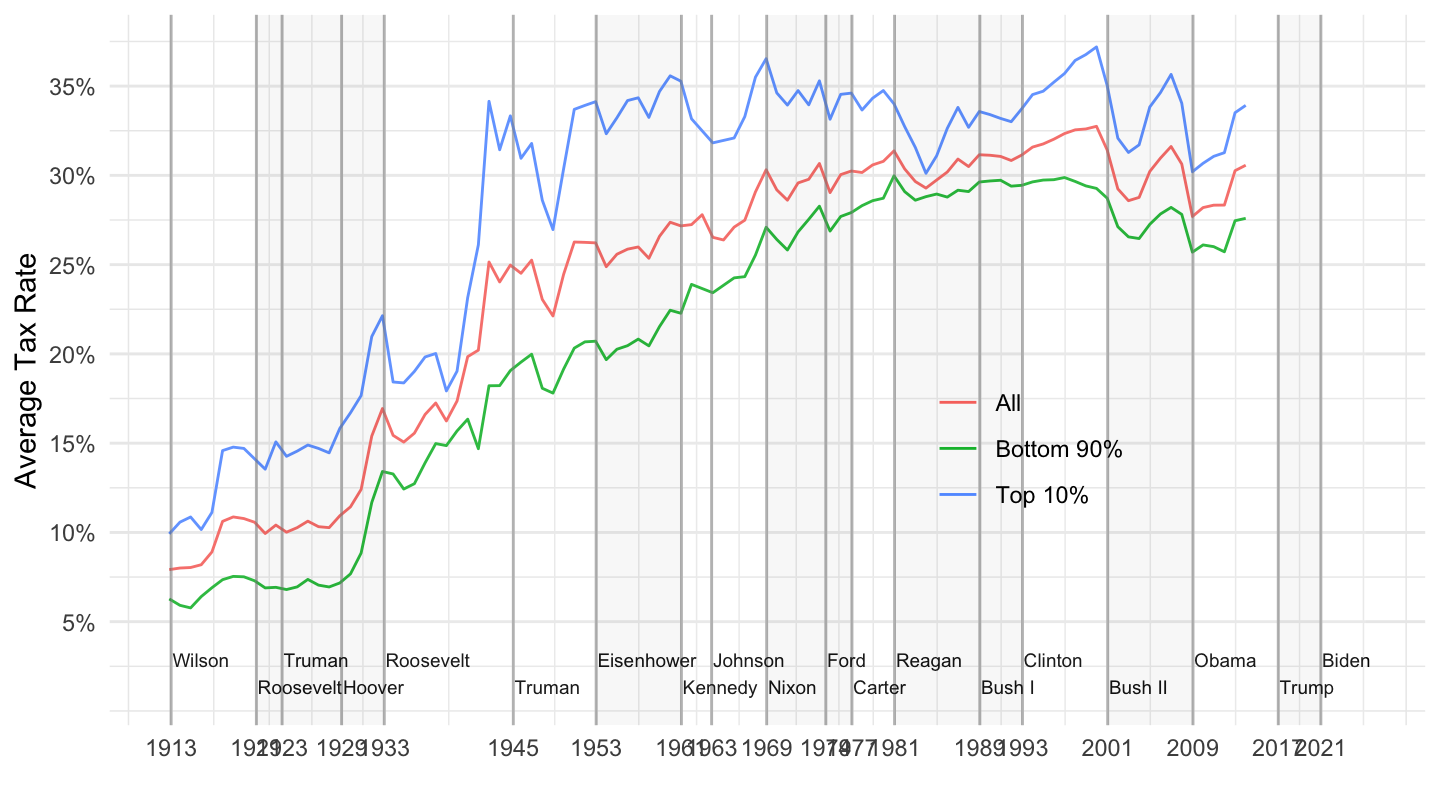

Average Tax Rates - Top 1%, Bottom 50%

Average Tax Rates - Top 1%, Bottom 50%

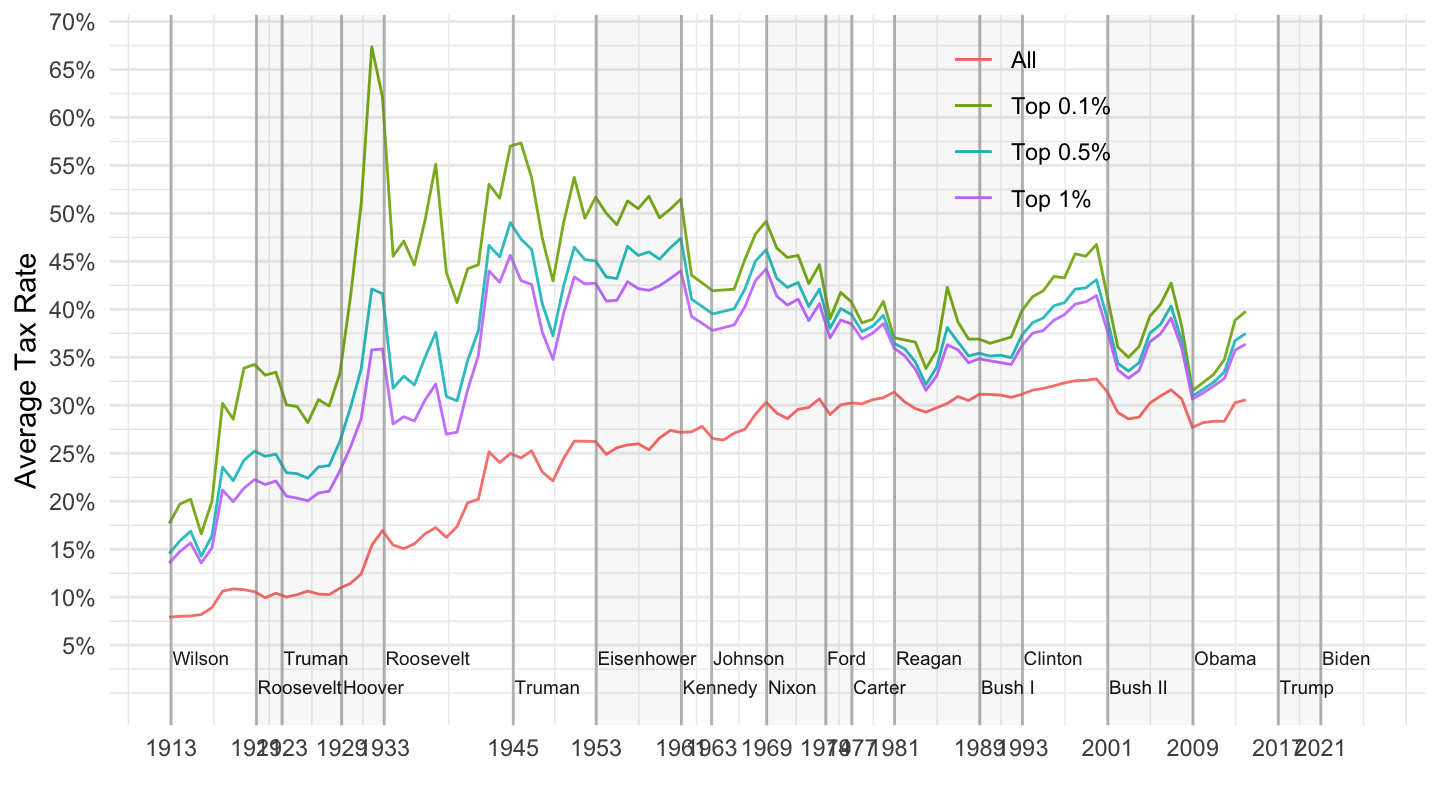

Average Tax Rates - Top 0.1%, 0.5%, 1%

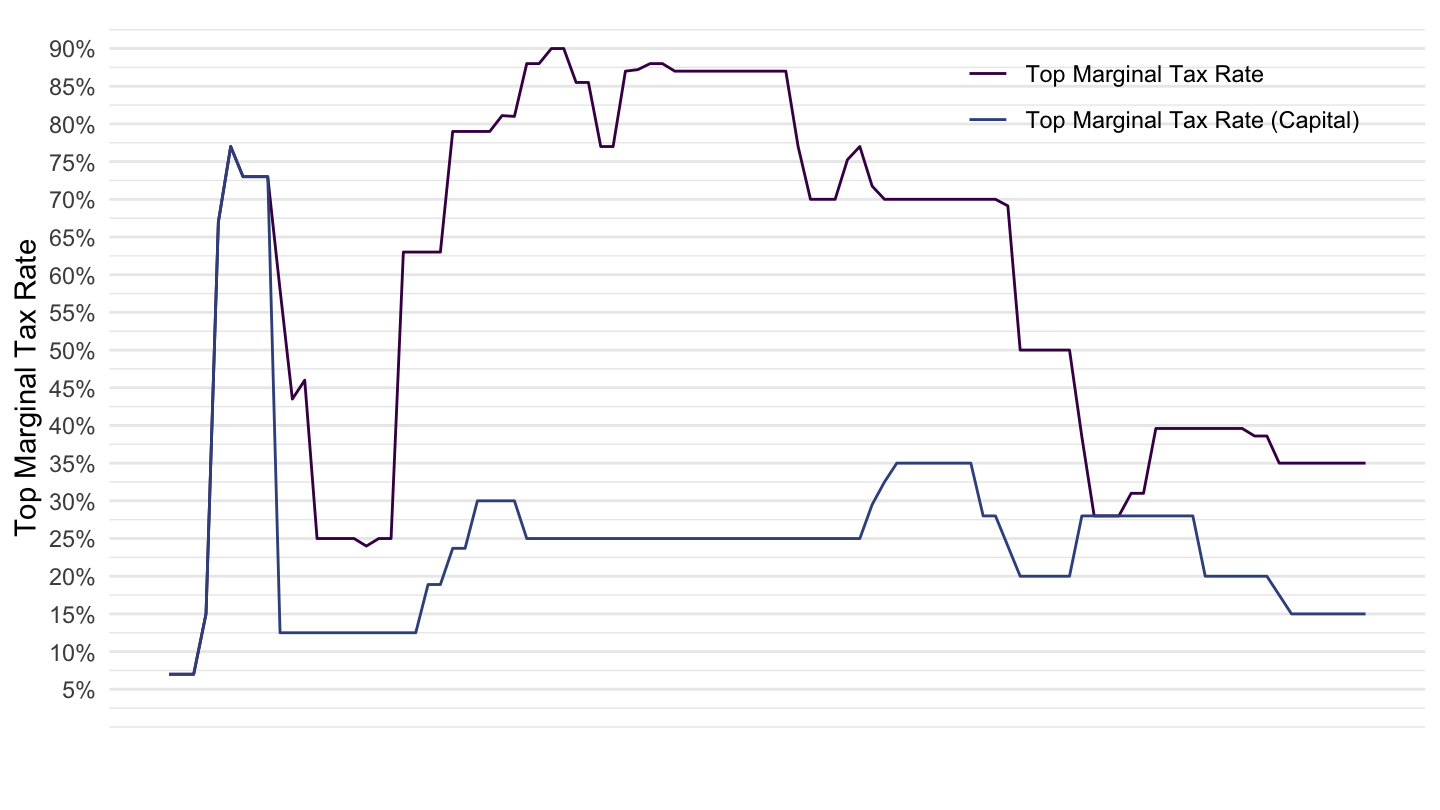

Top Marginal Tax Rates

Examples

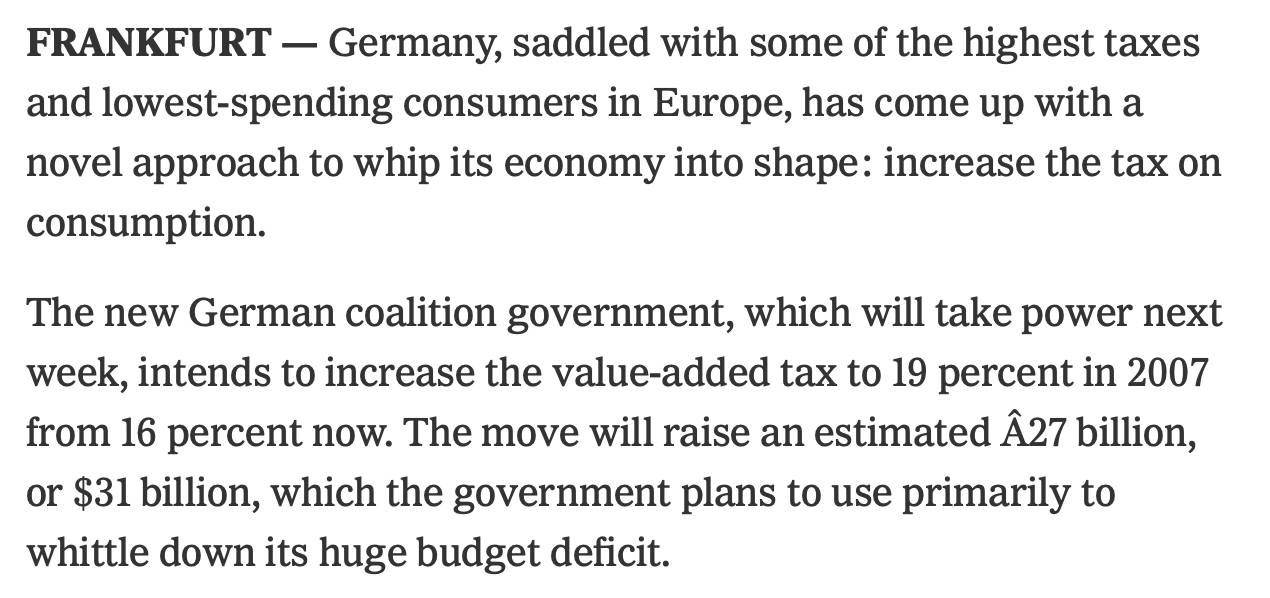

Germany’s VAT Tax Increases

Germany’s VAT Tax increase in 2007: 16% to 19%

Germany’s VAT tax increase in 2007: 16% to 19%

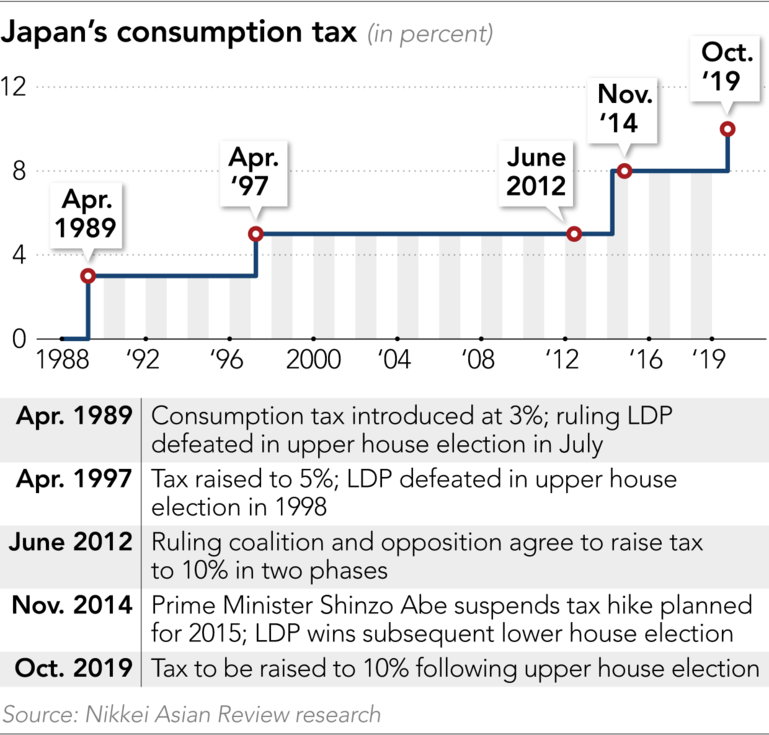

Japan’s Sales Tax Increases

Japan’s Sales Tax Increases

Japan’s Sales Tax Increases

Japan’s Sales Tax Increases

Japan’s 2014 Sales 5% to 8%

Japan’s 2019 VAT 8% to 10%

Wall Street Journal

Readings

Appelbaum - Blame Economists for the Mess we are in

- “Blame Economists for the Mess We’re In,” Binyamin Appelbaum, New York Times Online, August 25, 2019. html

Scrooge Mc Duck

- Corporations and wealthy households increasingly resemble Scrooge McDuck, sitting on piles of money they can’t use productively.

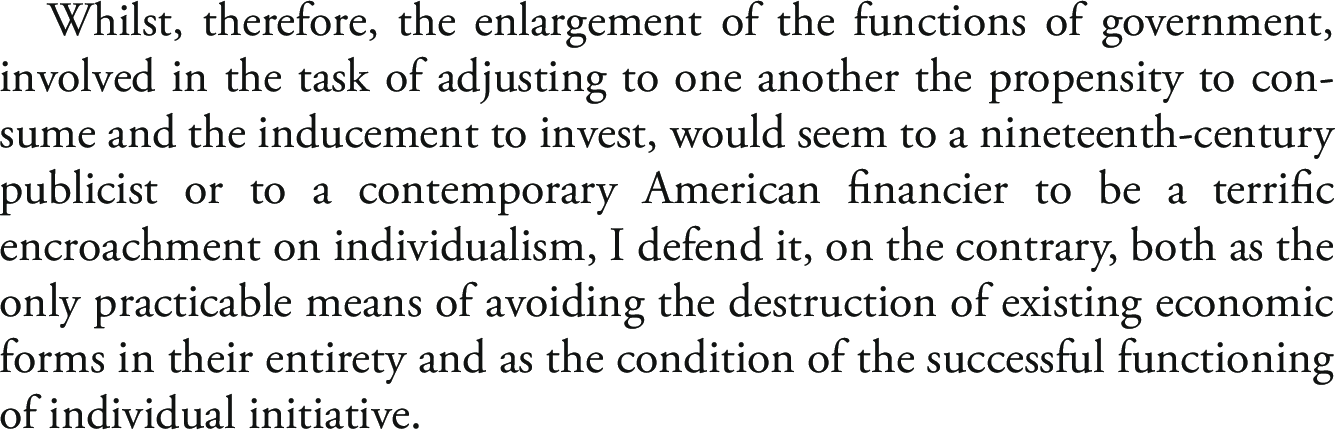

Where the poor and rich spend really spend their money

- Ehrenfreund, Max. The Washington Post. April 14, 2015. html