The Paradox of Thrift

Intermediate Macroeconomics - UCLA - Econ 102

François Geerolf

October 14, 2020

The Paradox of Thrift

Definition

According to the paradox of thrift, efforts to save more might be self-defeating and in fact lead to less saving and investment.

In neoclassical economics, saving can sometimes be “too high” (dynamic inefficiency); however by assumption more saving always translates into more investment.

According to one version of Keynesian economics, this is not correct: investment does not depend much on the cost of capital.

This could be due to the fact that the growth rate \(g\) is a lower bound for \(r\) (capitalists never want a lower return than that; if returns get lower, they just stop investing)

Keynes (1936) - Chapter 7

This phenomenon was explained by J.M. Keynes in Chapter 7 - “The Meaning of Saving and Investment Further Considered” of the General Theory:

Keynes (1936) - Chapter 24

Keynes restates the paradox of thrift in Chapter 24 “Concluding Notes on the Social Philosophy Towards which the General Theory Might Lead.”

In this chapter, Keynes argues that a higher saving rate (lower propensity to consume) need not increase capital accumulation. On the contrary, it might lower it:

Chapter 24: the vanishing importance of thrift

Counterintuitive? Immoral?

Idea that thrift is always virtuous is very deeply ingrained in our culture.

It is a matter of philosophy, morals, and sometimes even religion. (e.g. the “protestant ethic”)

For example, in the Walt Disney movie Mary Poppins, Michael is being lectured by a banker that he should not be “feeding the birds” (=spend) but instead invest his tuppence “wisely in the bank” to “be part of railways through Africa; Dams across the Nile, fleets of ocean Greyhounds; Majestic, self-amortizing canals; Plantations of ripening tea” (save and invest).

Interestingly, these capital investments are all abroad; we shall come back to this later.

Walt Disney movie Mary Poppins

Paradox of thrift by Samuelson (1948)

Counterintuitive? Immoral? - Samuelson (1948)

Neoclassical VS Keynesian regimes

Benjamin Franklin

Before J.M. Keynes

Very early

The paradox of thrift was known before J.M. Keynes, perhaps in the Book of Proverbs:

There is that scattereth, and yet increaseth; and there is that withholdeth more than is meet, but it tendeth to poverty. (Proverbs 11:24)

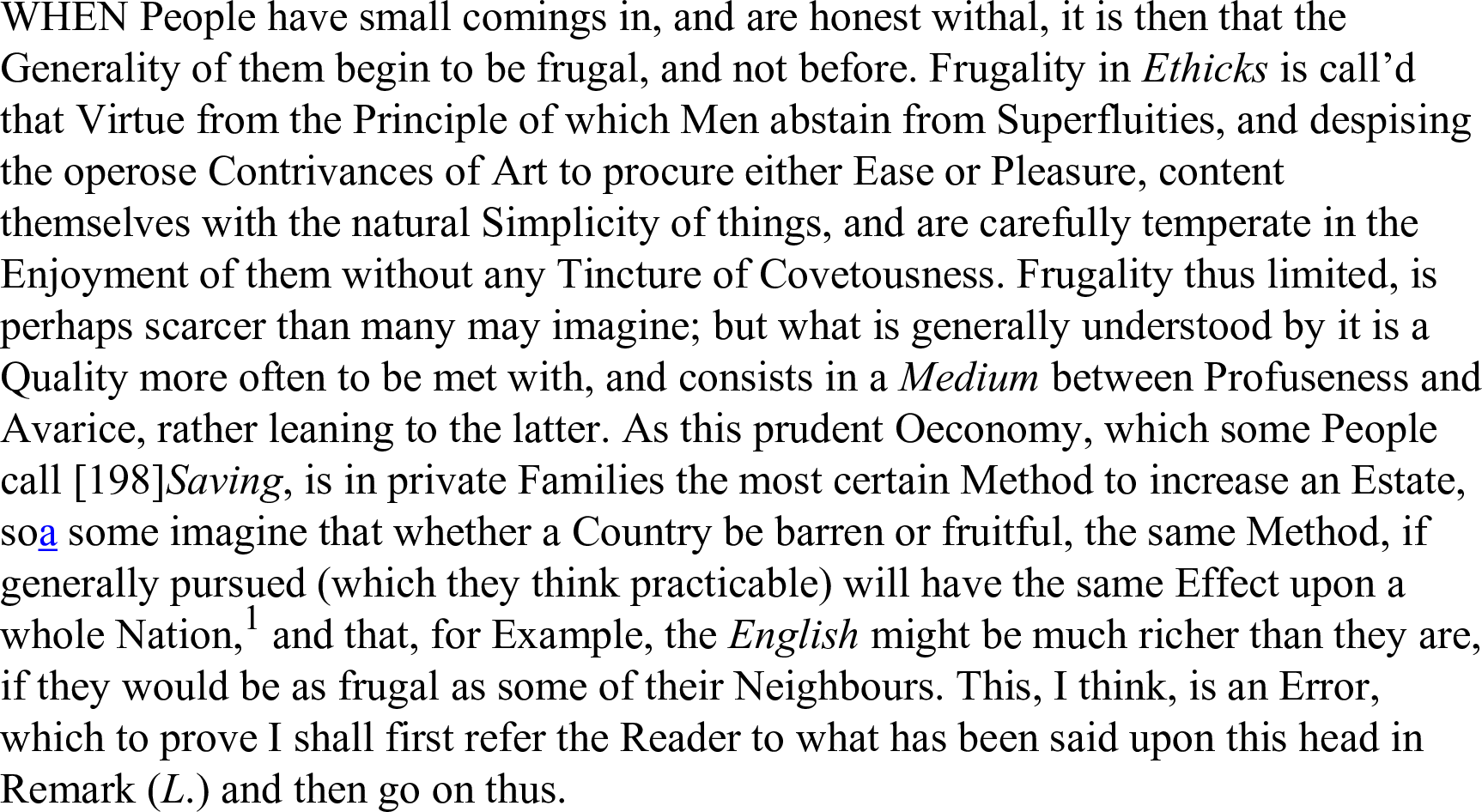

More certainly, it was present as early as in Bernard Mandeville’s The Fable of the Bees: or, Private Vices, Public Benefits (1714):

As this prudent economy, which some people call Saving, is in private families the most certain method to increase an estate, so some imagine that, whether a country be barren or fruitful, the same method if generally pursued (which they think practicable) will have the same effect upon a whole nation, and that, for example, the English might be much richer than they are, if they would be as frugal as some of their neighbours. This, I think, is an error.

Bernard Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees (1714)

Bernard Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees (1714)

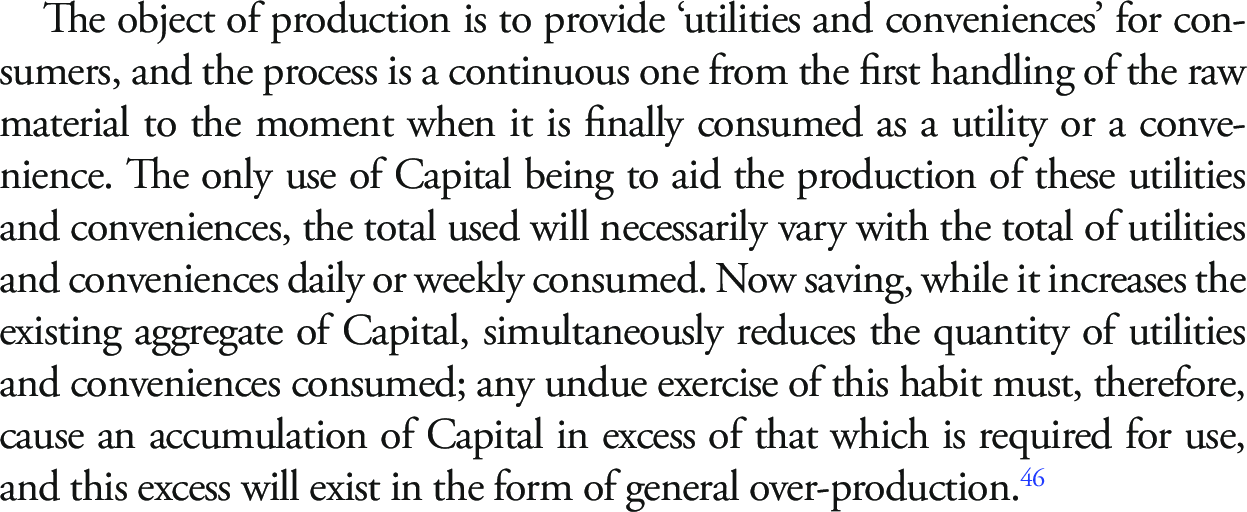

Malthus (1820) - Principles of Political Economy

Malthus (1820) - Principles of Political Economy

Malthus (1820) - Principles of Political Economy

Crocker and Macvane (1887) - General overproduction

Hobson

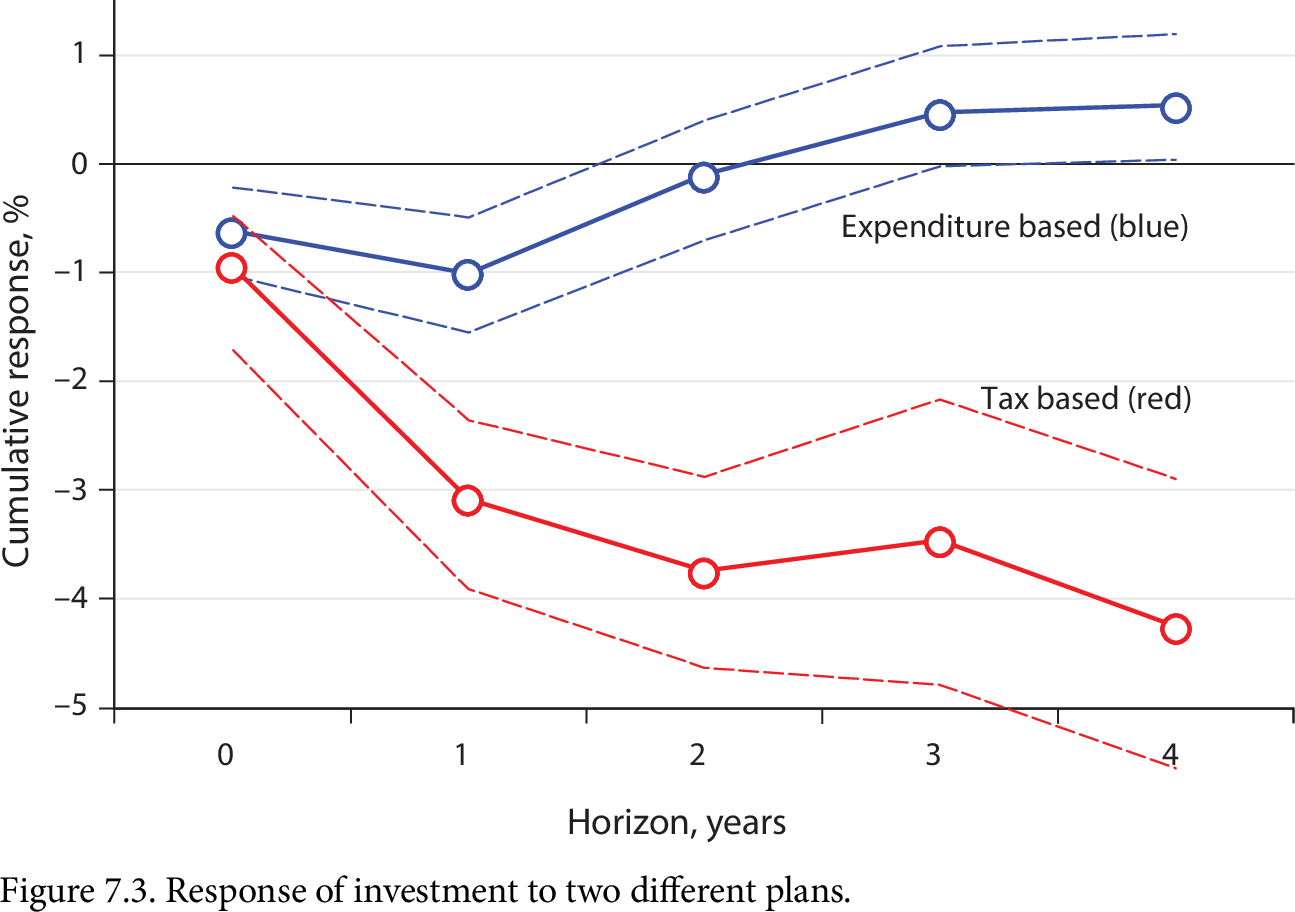

Austerity leads to a fall in investment

Crowding in, Paradox of thrift

- A rise in public saving, according to neoclassical economics, should boost investment.

Alesina, Favero, and Giavazzi (2019)

Alesina, Favero, Giavazzi now agree that tax-based austerity generates a long-run fall in investment. Note:

Also pervasive: same using Romer and Romer (2010)’s narrative fiscal shocks.

More generally: consumption, investment and output are positively correlated even conditional on aggregate demand shocks.

Alesina, Favero, and Giavazzi (2019)

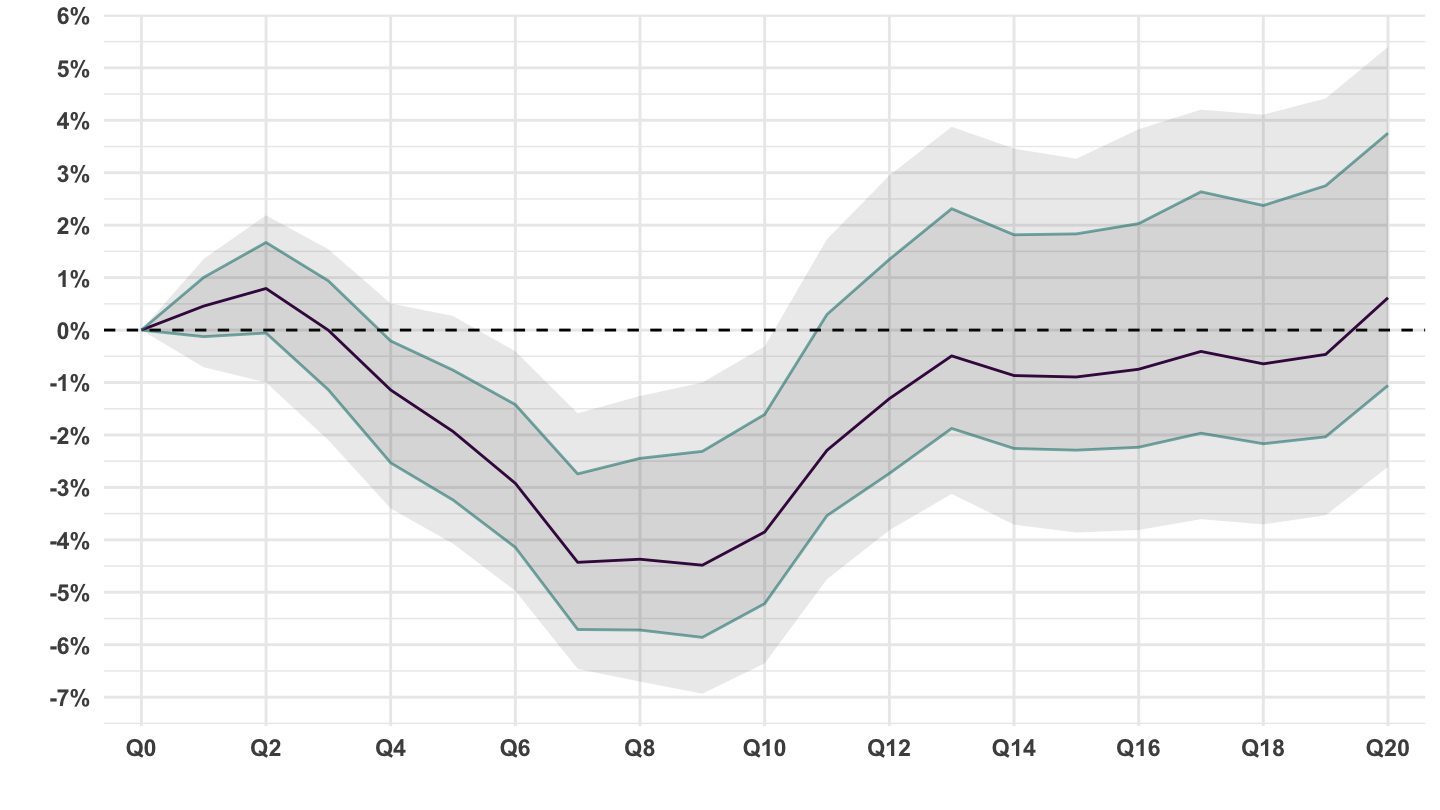

Romer and Romer (2010): Investment

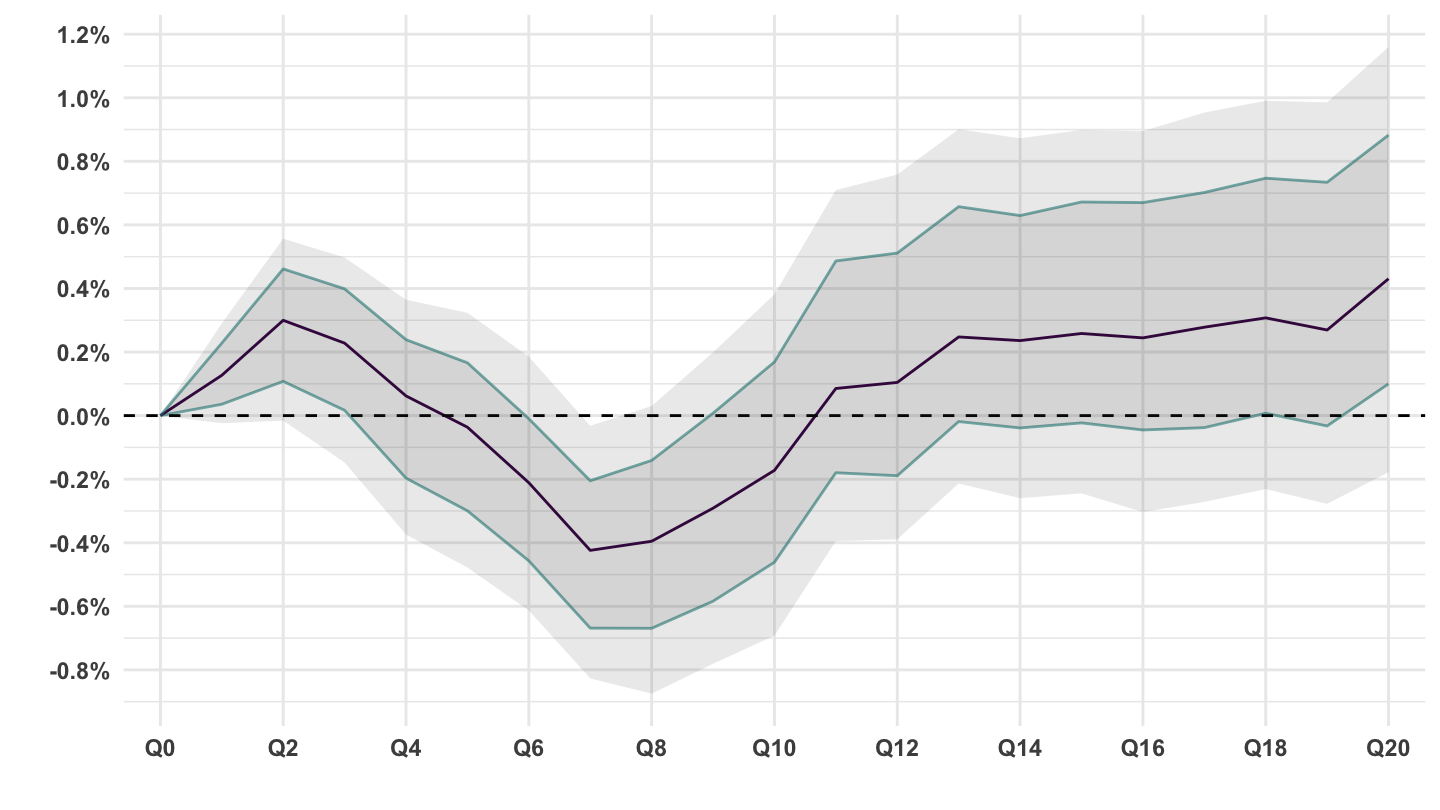

Romer and Romer (2010): Saving

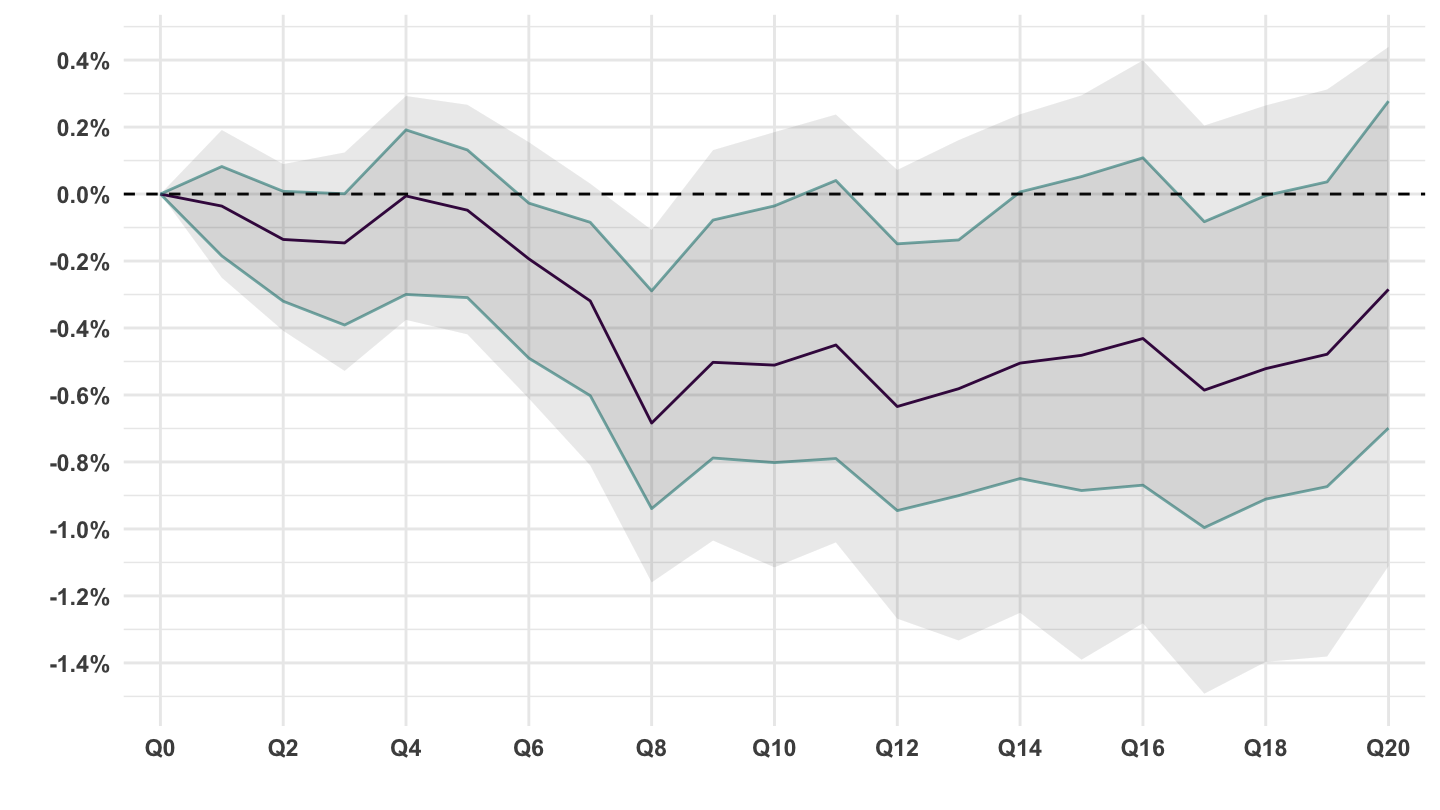

Riera-Crichton, Vegh, and Vuletin (2016) - Investment

Riera-Crichton, Vegh, and Vuletin (2016) - Saving

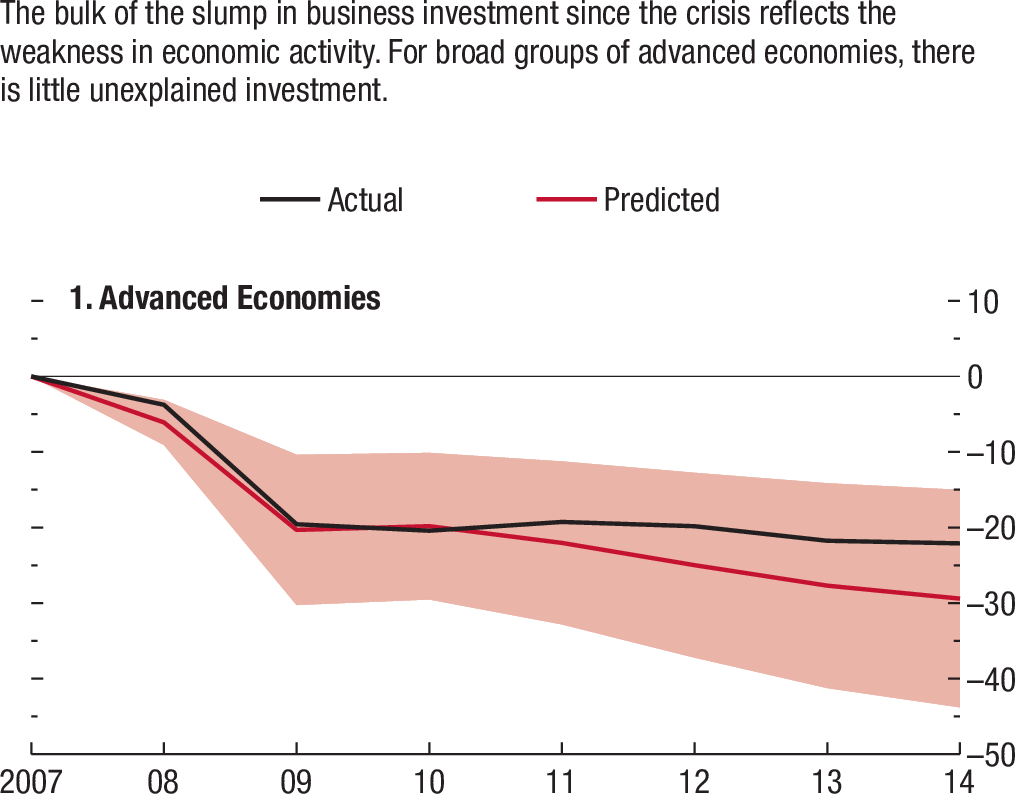

World Economic Outlook 2015 (IMF)

Krugman

Krugman

Ricardian equivalence or the paradox of thrift

Link

This absence of crowding out effect is in fact what motivated the idea of “Ricardian” equivalence: Robert Barro’s explanation for the absence of crowding out of lower taxes was that people saved in anticipation of future taxes to come. But Ricardian equivalence does not actually explain the crowding in that we observe. Moreover, people did consume more when taxes fell. The increase in saving came from higher employment and GDP.